“The discovery of a new dish does more for the happiness of the human race than the discovery of a star.” - Brillat-Savarin

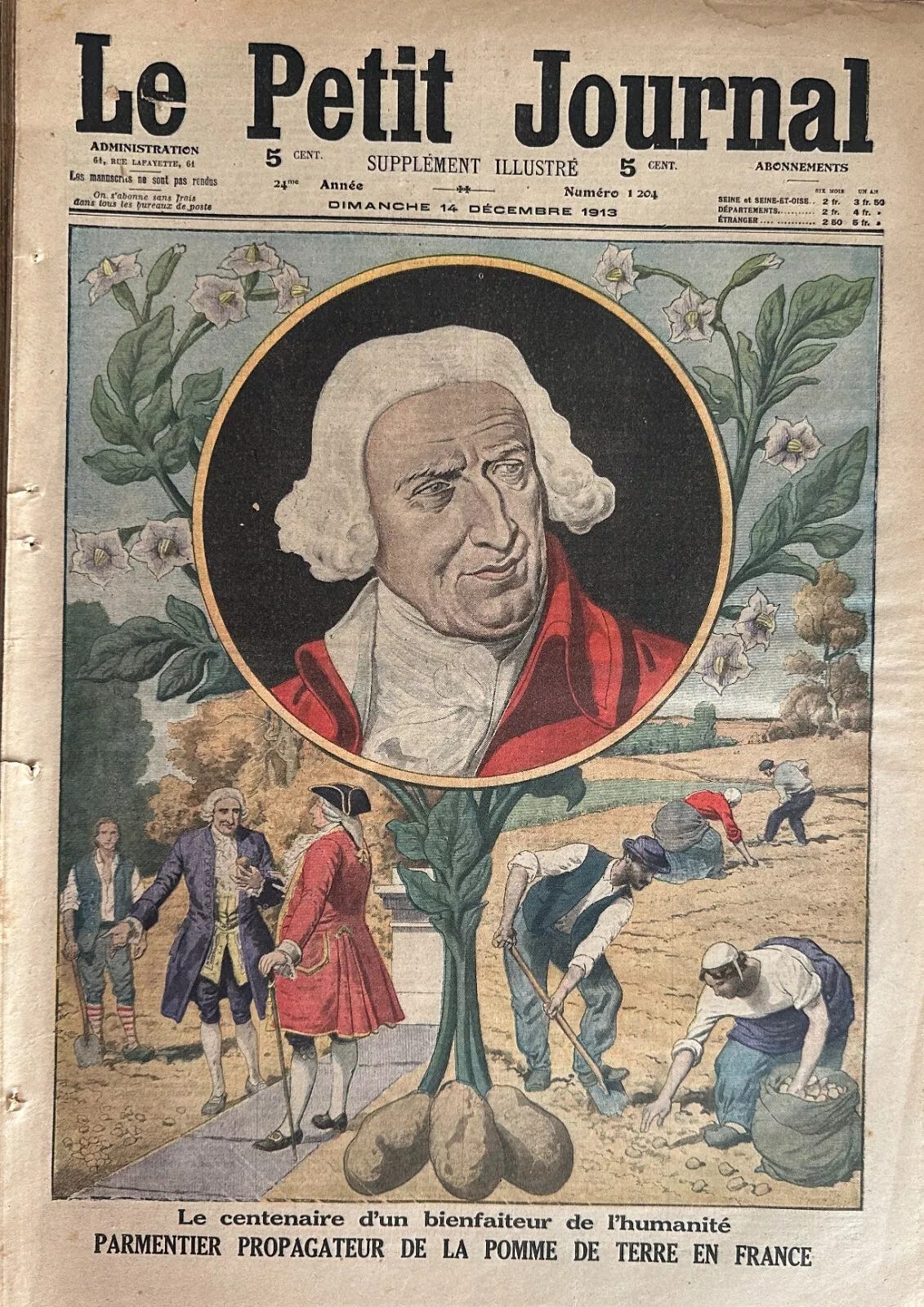

“Of all the illustrious men whose names have been celebrated by posterity, are there many more entitled than this one to the fine title of “benefactor of humanity”? So wrote Ernest Laut in the special issue of Le Petit Journal in December 1913, an issue dedicated to the 100th anniversary of the death of Antoine Augustin Parmentier, the man who popularized the potato in France.

Joseph Favre has an excellent and amusing entry in his Dictionnaire Universel de Cuisine Pratique (1893) on the potato. After musing briefly on the confused origins of the tuber, he dives quickly into its arrival in Europe. And, as usual, it seems that everyone else received the potato with open arms, where, over about half a century, it was embraced, widely cultivated, and eaten in Iceland, Scotland, England, then Spain, Italy, Germany, Flanders, Holland, Switzerland, and Lorraine, the territory in what is now France that borders on Belgium, Luxembourg, and Germany. And yet the French, right smack in the center of this whirlwind of spuds, looked down upon this root vegetable as being either dangerous or beneath human consumption. Alexandre Dumas, while claiming it was brought over in 1585 by Sir Walter Raleigh in his Grand Dictionnaire de Cuisine, admits “As for the potato, absurd prejudices long prevented it from being appreciated at its true value; for many, it was a dangerous food, at the very least coarse, and at most good for pigs….we (the French) didn’t accord much attention to it.”

Parmentier never pretended that he brought the potato to France, in fact, he was aware that several men, both politicians and scientists, some even on the advice of Parmentier himself, had fields of potatoes planted in various regions around the country; he knew that the potato was being cultivated and eaten, but primarily by the poor who could afford little else. What he did recognize was that it was neither appreciated nor fully exploited for the greater good. He knew that for many people of his own class, the potato was good for nothing more than animal feed.

Towards the end of the 18th century, at the time that Parmentier and several other men of science had been studying the potato and vaunting its qualities, an Englishman, Arthur Young (who once dined with Parmentier), traveled around France to study the consumption of the potato. He discovered that 99% of the French refused to use the potato as food for themselves. While they no longer believed that the potato could give them leprosy, once a common conspiracy theory (propagated by the parliament of Besançon and their 1630 edict prohibiting the growing of potatoes for this very reason), many did believe it was a poison, only good for medicines, if at all. As for the rest, well, it was good enough for the pigs. “As for noblemen and bourgeois, they would blush to find it on their table!” That’s where France was at the end of the century; it’s what Parmentier was up against when he began his theoretical and practical studies of the potato.

“The townspeople regarded the potato as a vile, coarse fruit, intended more for animal than human consumption, and placed it alongside the acorn.” - Histoire de la Pomme de Terre by Ernest Roze 1898

Everyone has heard of Parmentier, at least a dish called Parmentier, but not everyone is familiar with the man or his work and what he did for the common potato and, as one could say, for modern French cuisine. Antoine Augustin Parmentier was a 17/18th century military pharmacist, apothecary, agronomist, nutritionist, and hygienist; he discovered the nutritional benefits of the potato during his captivity in Prussia during the Seven Years' War - where he was apparently held for a terrible 3 weeks - as potato porridge was all that was fed to the prisoners. Once he returned to France in 1763 and obtained his diploma and status as apothecary 3 years later, he took on the tuber as his life’s work.

It was an uphill climb.

Denis Diderot, famed French writer, philosopher, and all-around erudite, wrote about the potato in his Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire Raisonné des Sciences, des Arts et des Métiers (1751-1765): “This root, however you prepare it, is bland and mealy. It cannot be counted as a pleasant food, but it provides abundant, wholesome nourishment for people who are just looking for sustenance. The potato is rightly criticized for being windy, but what are the winds to the vigorous organs of farmers and labourers?”

No small potatoes, either Diderot or his disdain of the tuber. Until famine hit France.

At the end of the 1760s, large swaths of France were ravaged by famine, intensified by resulting outbreaks of typhoid, decimating a large part of the population; at least 1.3 million deaths were reported. Parmentier entered a competition held by the Academy of Besançon (oh, the irony!) in 1772 on the subject “Which plants could be substituted in case of famine, and how should they be prepared?” entering his recipe for potato bread, the idea of which was to promote potato starch, something he had been working on as a substitute for wheat in bread-making, potatoes much more available to the people in times of famine than wheat. In 1772, he published his memoir, Examen Chimique des Pommes de Terre, Dans Lequel on Traite des Parties Constituantes du Bled (Chemical examination of potatoes, in which the constituent parts of grain flours are discussed).

And yet while Parmentier is making a name for himself, there had already been an ongoing discussion of the merits - or lack thereof - of the potato. The agronomist François-Georges Mustel had written a book on the potato in 1767, Mémoire sur les Pommes de Terre et sur le Pain Oeconomique, using the potato starch to replace wheat flour (later accusing Parmentier of having stolen his ideas). One only has to peer into the sepia pages of the Gazette du Commerce newspaper beginning in the year 1763 to follow the growing discussion of the root. Some contributors talked about the popularity of the potato in other parts of Europe. In the 10 March 1764 issue, a letter written to the editor complains that the French consume so much more bread than the English yet refuse to use the potato in place of wheat which - the potato - is more nourishing and less costly. In the issue of 7 April of the same year, it is again argued that “while the French consume more wheat than the English (for bread) and only have that (wheat) to live on and yet (the Frenchman) doesn’t grow potatoes (in italics) which would nourish him so much more agreeably, yes there are no potatoes in France and that is by choice!”

These agronomists are getting feisty! But they were still not quite getting their message across to the population.

Until bad wheat harvests across France in 1773 and 1774 led to dizzyingly high prices for both flour and bread and causing yet another famine. Riots broke out in many regions as the government tried to ease food shortages though changing grain trade policies (the groaning bells of revolution are beginning to toll). The time was ripe for these men of science to convince the population of the utility of potatoes and potato flour.

By 1768, news in the Gazette implies that the popularity of using potato flour (or starch) to make bread is now growing, by necessity, causing “the cultivation to spread into new regions, a healthy food for both men and beast.” In the 21 July 1770 issue, the discussion about using potatoes to make bread rages, with a reader sending in a letter explaining that many people are still having trouble doing so and he has a good method that works. In the 19 October 1771 issue, one Mr. Hey, a pastor in Germany, sends in his method of making cheese from potatoes. Cheese! Mr. Parmentier finally steps in, sending in a long letter to the editor on how to make bread from either chestnut or potato starch, taking the matter in hand. In 1774, a letter is published from a Mr. Hell responding to an earlier letter from a Mr. Bonet in order “to dispel his doubts and overcome his incredulities.” Mr. Hell urges the gentleman to “come visit our region. He would learn that, without the potato, half the inhabitants of these mountains would have died of hunger during the grain crisis over the course of these last years. He would learn that a half-square will feed an entire family for a year. He will learn that potato crops don’t deteriorate the earth, but quite the opposite and that they can successfully plant and grow wheat and spelt in the fields directly the potatoes are harvested. He will see that the workers make bread blending potato with oat flour and that this bread is more flavorful than that made with wheat. He will learn to eat potatoes and find them good and will, no doubt, make amends to them.”

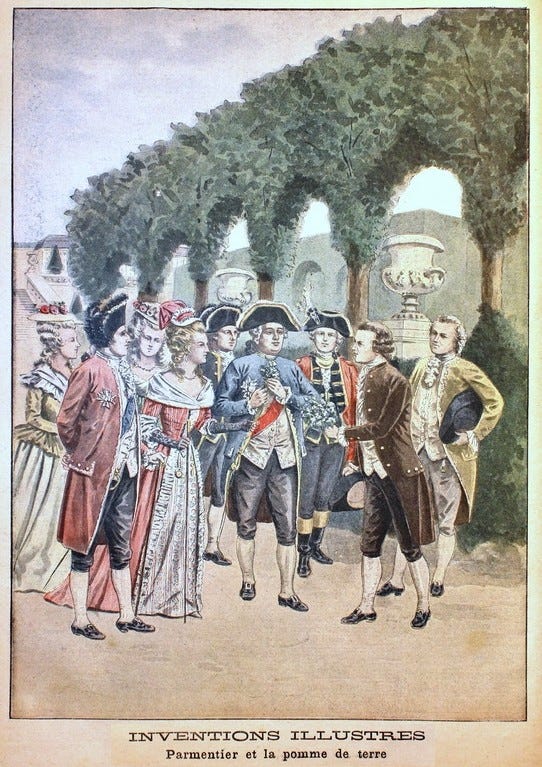

Meanwhile, Parmentier continued his work and his proselytizing, making every effort to bring his studies and his defense of the potato to the highest in the land, ministers and, finally, to the king himself. In 1785, he arranged to bump into Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette, offering the two a bouquet of lovely little flowers of the potato plant. He spoke to Louis at length about the potato and its possibilities. The King, considering himself an amateur scientist and botanist, was very interested, and allowed Parmentier to plant potatoes in the Plaine des Sablons, on the outskirts of Paris. Which he immediately did. Parmentier, knowing full well the character of Parisians, insisted the fields be heavily guarded by rows of soldiers, exciting the curiosity of the population and creating a stir, drawing nosy onlookers and much talk.

Once the crops were harvested, he had access to the King’s kitchens to study the different ways the potato could be prepared, creating first a creamy potato soup, which was to be named Parmentier. He and the king’s chefs cut and sliced the potatoes in a variety of ways, then fried them, turned them into croquettes, made gratins and sweet galettes. A banquet was organized, and these new foods created from a once-disdained vegetable were served to princes, influential scholars and prominent figures of society - the eras “influencers” - as well as to a number of servants. The following day, Parmentier had the menu published in one of the rare newspapers of the capital, creating a buzz across the city, and the French potato was born. As he wrote in his book Traité sur la Culture et les Usages des Pommes de Terre, de la Patate, et du Topinambour in 1789, “The ease with which the potato lends itself to all sorts of transformation and interpretation, gave me the idea of creating an entire meal to which I would invite a number of enlightened and enthusiastic amateurs selected from different ranks. The dinner was festive; and contrary to the usual opinion that this root is heavy, indigestible, and makes one drowsy, it produced quite the opposite effect on our guests.” His menu included potatoes turned into excellent meatballs, served in salads, steamed, in cream sauce, with cod, in stews, fried, served with legs of lamb, and in turkey and goose stuffings.

But was the potato - pomme de terre - really catching on? Its very late appearance in dictionaries might have suggested otherwise. It only (possibly for the first time) appeared in 1767 in Noel Chomel’s Dictionnaire Oeconomique as pomme de terre: voyez truffe (see truffle) with no definition. If one digs a little deeper and thinks to wander to the word patate, apparently a variety of the potato (pomme de terre), one would find “they are useful to feed and nourish people and animals. They are cooked in water or in ashes (fire). They are cooked, peeled, and sautéed in butter with onion, salt, pepper, and a little vinegar. Or they are served with cod in a white sauce. They are good served with leg of lamb or cooked with lard/bacon. Some eat them grilled with salt and pepper. When one is accustomed to eating this food, it is pleasing to the taste, at least as much as the turnip; especially if one cooks it with bacon and salt pork.” (Well, anything cooked with bacon, am I right?) A quarter of a century later, M. Vial-Duclairbois includes a very long discussion about the properties of the potato as an antiscorbutic, preventing scurvy among sailors, in his 1793 sea-faring Dictionnaire Encyclopédique de la Marine. Not only does he rave about Parmentier’s bread made only with potato starch, but he urges someone to invent a “sea biscuit” out of the same that sailors can carry with them on their voyages. Which, of course, Parmentier soon did. M. Vial-Duclairbois defends Parmentier against attacks, saying that “he never meant his bread or cookies made with potatoes to replace those made with wheat flour; he simply wanted to create something that could be used if the need arose.”

By 1793 (and his patron’s untimely beheading), not only had Parmentier convinced the general population of the advantages of the potato, but they had, by this time, become indispensable (potatoes, not people). A republican decree was sent out ordering a census of luxury gardens in order to dedicate them to the cultivation of this vegetable; as a result, the main avenue and the flower beds of the Tuileries Gardens were planted with potatoes.

And now the arrival of the Emperor Napoléon Bonaparte. He, contrary to his headless predecessor, was said to tolerate the potato but not enjoy it, even as it was often served on his table. It was evidently not part of the military’s regular rations - he supposedly stated “An army of potato eaters will never be able to beat an army of wheat eaters”. But potatoes were eaten by the soldiers, often because there was little else. Constant Wairy, long Napoléon’s personal valet, wrote in his memoirs “His Majesty, visiting the line of attack where food was in short supply, saw soldiers busy cooking potatoes in the ashes as he passed from bivouac to bivouac. The Emporer says to a grenadier of the 2nd battalion, as he picks up and eats one of the squad's potatoes: ‘Are you happy with those pigeons?’ “Hum! - It's always better than nothing, but those pigeons are Lenten meat.” (meat was not eaten during Lent) - ‘Well, old chap,’ resumed His Majesty, pointing to the enemy's fire, ‘help me flush out these b…s and we'll celebrate Mardi Gras in Vienna.’”

Victor Forbin sums it up quite nicely in his homage to the potato in the 11 September 1932 issue of Ève, the first illustrated daily newspaper for women: “The list of benefits for which the Old World is indebted to the New would be fairly long. Let's limit ourselves here to the most important one, which is, without a doubt, the humble potato. Humble? The epithet is hardly appropriate for this conqueror which, despite its modest beginnings, has brought all the temperate regions of the globe under its dietary influence.” And he concludes “I'd be remiss if I didn't mention the thousand and one ways in which our fine French chefs accommodate these precious tubers. And it's worth noting that everywhere else, potatoes are eaten in only two forms: boiled in water or mashed. I wouldn't be surprised if the fried potato was a French invention.”

Parmentier brought the potato to France, and got his statue. The merit was great and well deserved. - Pierre Lacam, Le Glacier Classique et Artistique, 1893

Pâté de Pomme de Terre - Potato Tart

So simple, but so very, very good!

I was intrigued by this potato tart when I came across it in my research. La pâté de pomme de terre - the potato pastry (pâté is usually thought of as a meat terrine, but pâté most surely comes from the word pasté which was a 2-crust fruit tart in the Middle Ages - is a popular traditional savory dish from the old Bourbon Duchy of France, supposedly born in the countryside in 1789, a year of famine in France. Before potatoes became a common foodstuff, this tart was made simply with leftover bread dough and cream or crème fraîche. Potatoes were added to make a meatless dish for Fridays, but it also quickly became a poor man’s dish when no meat was to be had at all.

This can be made in a deep pie dish, a cake pan, or freeform on a parchment-lined baking sheet. Increase or decrease the quantities of ingredients for the size you want. Adjust your baking time. I do suggest that the thickness of the tart (filling and crusts) is somewhere between 1 1/2 and 2 inches, not exceeding the 2 inches.

My potato tart took a total of 1-½ hours to bake completely; the top was a gorgeous golden brown, flakey and crispy, and the potatoes were perfectly cooked through (test by sticking a knife blade through the layers).

For a 10-inch x 2-inch (25-cm x 5-cm) cake pan; mine has a nonstick surface which worked fabulously.

About 600 grams puff pastry (pâte feuilletée) or 2-crust shortcrust pie/quiche pastry (pâte brisée), homemade or good quality store-bought (find my puff pastry recipe here)

28 to 35 ounces (800 grams to 1 kilo / 1.7 to 2.2 pounds) potatoes, *see note below

1 ⅔ (400 ml) half tangy crème fraîche (or Greek yogurt or sour cream) and half heavy cream

Salt

Freshly ground black pepper

Dried fines herbes or a mix of green herbs, or a choice of fresh or dried herbs, optional

Nutmeg

1 egg, beaten till blended, for egg wash

*Note: a firm-fleshed potato that will cook up tender yet hold its shape - a variety that is recommended for steaming or boiling; I use Charlene

Preheat the oven to 400°F (200°C).

If using a cake pan or pie dish, butter it well, bottom and sides, and flour, shaking out the excess flour.

Cut the puff pastry or shortcrust into two pieces, one a bit larger than the other. On a floured surface, roll out the larger piece thinly and to fit your cake pan or pie dish. Line the cake pan or pie dish, making sure the pan is lined all the way up the sides to the top edge of the pan.

If making this tart freeform, just roll the dough out large enough that you have at least 2 inches (5 cm) edge all around the filling.

Peel the potatoes; if you rinse the potatoes once they are peeled, pat them dry with a clean dishtowel or paper towels. Slice the potatoes thinly. Evenly fill the pastry crust with the potatoes (I layered them in overlapping concentric circles, but that’s not necessary), lightly dusting each layer with salt and pepper and some of the dried or fresh herbs, if using.

Roll out the remaining pastry thinly and into a round just the size of the cake pan or pie dish. Cut out a large circle, about 1-½ inches (3 - 4 cm) in diameter in the center of the round of pastry; alternatively you can make several holes around the top crust where you will be pouring the cream through. Carefully lift the dough and place on the potatoes; using a pastry brush, brush the top crust/pastry round with egg wash all the way to the edge. Fold the edges of the bottom crust up and over the edges of the top crust and gently press to “glue” or stick the two crusts together all the way around. Brush the edge all around with egg wash (the entire top crust is now brushed with egg wash.

Using a knife, gently mark the top crust decoratively.

Place the tarte in the oven for 30 minutes.

While the potato tart is baking, place the two creams in a large measuring cup with a spout. Add a pinch or two of salt, a good amount of freshly ground black pepper, and a couple of pinches nutmeg and whisk to combine. If the creams are very thick, whisk until the liquid is easily pourable, adding a dash of milk to slightly thin, if needed.

At the end of 30 minutes, the crust should be turning a beautiful light golden brown.

Now here is the tricky part.

Remove the tart from the oven and place on a steady surface that won’t burn - like large wooden cutting board on the counter. You want to pour the cream - give it a good whisk before pouring - into the tart through the hole in the top crust. Mine didn’t want to filter or seep down through the layers of potato slices…I ended up carefully putting a knife blade into the center hole, slightly lifting up a section of the crust without breaking it, pouring in some of the cream, removing the knife, shaking/jiggling the pan back and forth to get the cream to seep down into the layers of the potatoes, turning the pan a bit and repeating, all around the tart until all of the cream was in the potatoes. It was very fiddly but it ended up working beautifully.

Return the tart to the oven and continue baking for another hour - see my headnote above the recipe - or until the crust is a beautiful deep golden brown, flakey and crisp, and the potatoes are cooked tender all the way through - test by sticking a knife blade down through the layers.

Remove from the oven, let cool slightly, then slice and serve with a green salad.

Thank you for reading and subscribing to Life’s a Feast by Jamie Schler. Please leave a comment, like and share the post…these are all simple ways you can support my writing and help build this very cool community. Let me know you are here and what you think. You are so very appreciated.

Such an interesting background on the perceptions of the French on the potato, something I never knew existed (the negative perceptions), the potato advocacy that was needed albeit not successful until after thd 1789 Revolution. Thank you Jamie!! Thank you for this French Potato History!!

I will definitely try making this, but I especially LOVED reading the history of the potato. Your rendition was very entertaining.