Pâte feuilletée

A puff piece

Simplicity is the ultimate sophistication. – Leonardo da Vinci

Variations of savory and sweet confections made of superimposed paper-thin layers of dough separated by thin layers of fat, usually oil, were already being done centuries before arriving in France and, more importantly, before becoming the puff pastry that we are so familiar with today. Brik, bourek, briouate, pastilla, baklava, strudel, for example, have long been popular foods in countries from Turkey to Algeria and Morocco to Greece to Austria by way of (full circle) Turkey. But while the resulting pastries have something in common with puff pastry - pâte feuilletée - the process of creating the feuilles - leaves or layers - being the same basic process, the recipe is rather different. So how did anyone arrive at that butter-rich version of this ancient dough?

The first written mention of a pâte feuilletée was in 1604 in L’Ouverture de cuisine by the master chef - maître cuisinier - for the Prince of Liège, Lancelot de Casteau. His pastèz d’Espaigne fueiltéz - pâte d’Espagne feuilletée - was a base dough made of “the finest white flour you can get”, eggs, a little butter, and water, kneaded until smooth and soft, then allowed to rest. Once this enriched dough is “as tender as paper” it is rolled out and brushed with melted pork lard or butter, folded or rolled upon itself, rolled out and brushed with more of the melted fat, the process then repeated again (le tourrage). This pâte feuilletée was then used primarily for a variety of savory meat pies with seasoned and spiced finely chopped meats. Lancelot de Casteau’s meat pies sound very much like Spanish empanadas; pastèz d’Espaigne fueiltéz or Spanish puff pastry might very well refer to the dough used commonly during this period by the Spanish to make similar pastries, a dough brought to Spain by the Moors, the Muslims of North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula.

In 1895, Joseph Favre, “famously skilled” Swiss chef and political activist, creator of the journal La Science Culinaire, and founder of the Union Universelle pour le Progrès de l'Art Culinaire, wrote the influential Dictionnaire universel de cuisine et d'hygiène alimentaire. In it, he makes the claim that a Monsieur Feuillet, pastry chef for the Prince de Condé in the 18th century, was “the creator of puff pastry”.

But while Chef Feuillet might very well have refined the recipe, he most certainly did not create it, for feuilletage, paste de feuilletage, feuilletées were already written about in cookbooks a century or so earlier, Lancelot de Casteau’s L’Ouverture de cuisine, case in point.

A fairly common yet difficult-to-prove legend actually credits the painter Claude Gellée, called Le Lorrain, for creating pâte feuilletée. Born in 1600, he was sent out to train as a pastry chef at 12 years old and worked on and off as a chef pâtissier many years of his life while trying to earn his bread (haha sorry for that) as a painter. It’s said that he tried several ways to invent a butter-rich bread for his ailing father, finally coming upon something close to a puff pastry. The butter, layered in between layers of dough, melts, and the water released by the melted fat, instead of creating a soggy bread, turns to steam, pushing the baking layers of dough away from each other creating the delicate leaves.

Whether this story is true or not, it is about this time recipes for pâte feuilletée - what the 1767 Dictionnaire portatif de cuisine describes as une pâte mariée avec du beurre, de telle sorte qu’elle se lève en feuillet - a dough married with butter in such a way as it rises in leaves - began appearing.

François Pierre de La Varenne, chef of the Marquis d’Uxelles, wrote one of the most influential cookbooks of modern French cooking, Le Cuisinier François, first published in 1651, covering both cooking and pastry; Le Cuisinier François is considered the first cookbook to put into practice the considerable culinary innovations accomplished in France in the 17th century by codifying cooking in a methodical way, writing recipes that a modern reader, and not only practiced chefs, would find understandable and clear to follow. His lengthy 2 ¼ page recipe for paste feüilletée is familiar to any student today in any pastry class: he makes a détrempe, the starter dough, out of fine wheat flour, salt, and water until molette, soft and damp, the dough then left to rest. The dough is then rolled out to the thickness of a thumb (or an inch). Fresh butter (firm, not soft) is then shaped to the size of the dough, the four corners of the dough are then folded over the butter so the butter is well enclosed inside the dough. He then continues with the rolling out, folding, repeated again and again… Curiously, his recipe includes a mention of using this dough to make a pigeon tourte, instructing that it should be rolled out to “the thickness of a silver Louis ecu coin”.

Agronomist and valet of Louis XIV, Nicolas de Bonnefons, wrote a wildly popular set of books in 1651, the tome Le Jardinier François and its companion Les Délices de la Campagne, both dedicated to les dames menagère, basically housewives, or women who ran households; the first, a complete gardening manual, the second a cookbook which, I assume, tells the little lady what to do with the produce from her garden. His early editions of Les Délices de la Campagne - I looked at one published in 1655 - included a détrempe for his “paste de feuilletage” that kneaded 12 eggs (!!!), a “boisseau” (that’s a heck of a lot) of fine wheat flour, and water very lightly with only one hand, until the dough is (again) molette. It is then rolled out to the thickness of one single finger, then wrapped like a serviette around a block of the same weight butter, rolled out then folded like a gateau de Milan - folding the two ends towards the middle, then rolled and folded again 4 times.

By the 1741 edition of his cookbook, de Bonnefons, does away with the eggs and has a recipe exactly like that in La Varenne’s Le Cuisinier François. Strangely, Le Cuisiner Royal written by André Viard in 1806 has a classic - for today - recipe for feuilletage in which he adds egg whites to his détrempe. I must try this recipe to understand what the egg whites do.

By the 1690s, puff pastry, pâte feuilletée or feuilletage, was commonly used in recipes both savory and sweet, if the many many times François Massialot uses it in his recipes in his cookbook Le Cuisinier Royal et Bourgeois is any proof.

By the time M. Feuillet went to work for the Prince de Condé, puff pastry was already a common culinary item, used quite prolifically in the preparations of all kinds of meat pies, tourtes, and pâtés, as well as tarts, specifically jam tarts.

Puff Pastry - pâte feuilletée

This might seem daunting, but if you have a long morning or afternoon and a lot of patience, making puff pastry is pretty straightforward, simple, and an absolutely sensual and satisfying project. Before starting, there are a few things to take note of:

It takes about 4-5 hours to prepare the puff pastry dough from start to finish although much of this time is inactive, just waiting for the dough to chill between turns…it can be stretched out over an even longer period of time if that better suits your schedule.

The refrigerator is your best friend when it comes to buttery puff pastry. Refrigerate the dough after every 2 turns (rolling out and folding), but if the weather or your kitchen is hot and the butter begins to soften or melt, the dough split and the butter oozes out, just refrigerate after each single turn/fold sequence for up to 30 minutes.

Keep the surface of the puff pastry as well as the work surface underneath the puff pastry floured at all times, dusting as needed, while rolling out the dough: dough that sticks to the work surface or rolling pin will tear, allowing butter to be exposed and ooze out and will make it hard to roll.

If the dough tears while rolling and butter is exposed, simply pinch the dough together over the exposed butter and rub a little flour into it.

I use a sewing tape measure to make sure my dough rolls out to the right length and width.

If you only have all-purpose flour, then use it in the place of both flours.

Make sure you understand all the steps, have the table space, extra flour on hand, and are prepared.

This recipe makes approximately 2 pounds/905 grams of dough

Make sure you understand the steps, have the table space, extra flour on hand, and are prepared.

Détrempe:

8.8 ounces (250 grams) cake flour

8.8 ounces (250 grams) bread flour (type 55) or all purpose flour

2 teaspoons table salt

2.5 ounces (5 tablespoons/70 grams) slightly softened butter

1 cup (250 ml) very cold water

Beurrage:

8.8 oz (17 ½ tablespoons/250 grams) cold unsalted butter in sticks or a block

Make the détrempe:

The détrempe or the basic dough can be made in a food processor, but I do this by hand in a snap.

Blend the 2 flours (or use all all-purpose) and the salt in a large mixing bowl. Add the 2.5 ounces (5 tablespoons/70 grams) butter cut into cubes and rub into the dry ingredients until it has disappeared. Add the chilled water all at once and stir until all of the dry ingredients are moistened and the dough starts to pull together. Add a tablespoon or two more water if needed.

Scrape out onto a well-floured work surface and knead for just a few minutes until the dough is smooth and pliable.

Form the dough into a ball, wrap it in a damp kitchen/dish towel and refrigerate for about 5 minutes (I slash the dough first).

Incorporating the Butter:

Place the butter between 2 sheets of plastic wrap and beat it with a rolling pin until it flattens into a square 1" (2 cm) thick. Take care that the butter remains cool and firm: if it has softened or becomes oily, chill it before continuing.

Remove the dough from the fridge. Working on a well-floured surface, roll out the dough into an approximately 10” square. Keep the top and bottom of the dough well floured to prevent sticking and lift the dough and move it around frequently to roll out evenly.

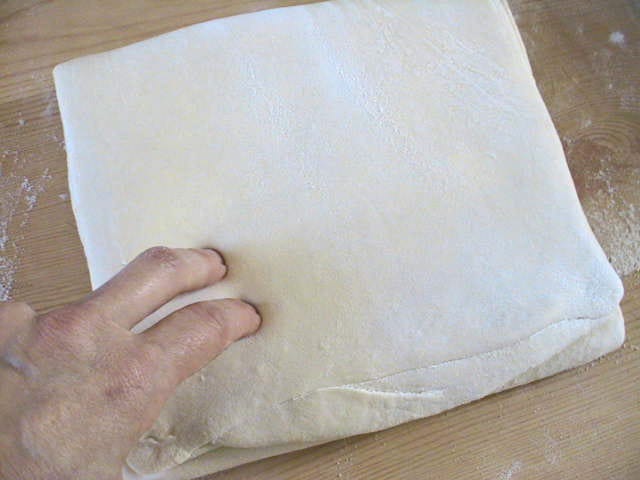

Starting from the center of the square, roll out over each corner to create a thick center pad with "ears," or flaps - you’re actually stretching/extending the 4 corners of the dough square. (in the photo you see me using the plastic-wrapped butter to measure that the dough is large enough to fold over the butter and meet to slightly overlap so the butter is completely covered in the dough)

Romove the square of cold butter from the plastic wrap and place the butter in the middle of the dough. Fold the ears over the butter, stretching them as needed so that they overlap slightly and encase the butter completely. (If you have to stretch the dough, stretch it from all over; don't just pull the ends) you should now have a closed package that is 8-inch square. Make sure it stays cool at all times; if need be just pop the whole thing in the fridge regularly for a few minutes until it firms up again. (note: you don’t want the dough to overlap too much or to have thick knobs of dough at each corner - this will be dough without an inner layer of butter and it’s the butter that makes the flaky layers).

Making the Turns:

Gently but firmly press the rolling pin against the top and bottom edges of the square “package” to seal (lay the rolling pin horizontally on the dough along each edge and press straight down), thus ensuring the dough stays square.

Keeping the work surface and the top of the dough well floured, roll the dough into a rectangle, perpendicular to your body, 3 times as long as wide (24” long, the width may vary between 8” and 9” but don’t worry). Make sure that the corners remain square and the 4 sides straight.

Don't worry if a bit of butter oozes out, just try and press the dough closed & sprinkle/rub with flour; the dough will be smoother with each turn.

Brush off all excess flour from the surface of the long rectangle of dough and fold the bottom third of the dough up to cover the middle third of the rectangle (mark off 8” down from the top and align the edge of the folded dough to this). Again brush off all excess flour from the surface of the folded up portion and bring down the top remaining third so the edge comes to the bottom edge (the dough is now folded into thirds (3 layers of dough), all edges even and no gaps. Pull gently on the corners if need be so there are no gaps. Gently but firmly press the rolling pin on the edges to “seal” (like you did at the beginning) so when rolling again the edges stay aligned.

Rotate the dough so that the closed fold is to your left like the spine/back book. Repeat the rolling and the folding process one more time. Once it is rolled out (24" long x 83 wide) and folded again into thirds, you have just completed the second turn.

If the dough is still cool and no butter is coming through the dough, you can give the dough another two turns now. If the condition of the dough is iffy and beginning to soften, wrap it tightly in plastic wrap and refrigerate it for at least 30 minutes.

Each time you refrigerate the dough, mark the number of turns you've completed by indenting the dough with your fingertips so you don't forget.

It is best to refrigerate the dough for 30 to 60 minutes between each set of 2 turns.

The total number of turns (rolling out and folding into thirds) needed is six. If you prefer, you can give the dough just four turns one day, chill it overnight, and do the last two turns the next day. Puff pastry is extremely flexible in this regard. However, no matter how you arrange your schedule, you should plan to chill the finished dough for at least an hour before cutting or shaping it for baking.

When you cut through the dough you should see all of the layers. So just make sure you understand the steps, have the table space, extra flour on hand, and are prepared.

Thank you for subscribing to Life’s a Feast by Jamie Schler where I share my recipes, mostly French traditional recipes, with their amusing origins and history. I’m so glad that you’re here. You can support my work by sharing the link to my Substack with your friends, family, and your social media followers. If you would like to see my other book projects in the making, read my other essays, and participate in the discussions, please upgrade to a paid subscription.

Our family’s traditional pastry at Christmas is quite similar, and originates in Slovenia. The walnut filling incorporates 12 eggs. There is also an Hungarian version.

Thank you for the history lesson. I’ve tried my hand at croissants and cornetti but have never tackled puff pastry. When I’m back on my feet...