L'éclair part one

A pipe dream

The three cities where the English stay longest are Pau in Béarn, Tours in Touraine, and Dinan in Brittany. Their pastry is a bit heavy, so they take revenge on ours, leaving a plum cake for an éclair. - Pierre Lacam

It’s quite a simple story, really. Talleyrand, that’s “Prince” Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord to you, statesman and Napoleon’s chief diplomat, wanted elongated cookies, something that wasn’t quite usual back then, that he could easily dip into a glass of Madeira, his favorite tipple. His chef, the great Antonin Carême, shaped sponge batter with spoons, and the biscuit à cuillère was born. Biscuits à cuillère - literally “cookies with the spoon” (or “by the spoonful”), sponge or ladyfingers, like choux (puffs), croquettes, meringues, and other small cookies, were dropped and shaped on a baking sheet using spoons, as was the method used up until Carême’s time as chef in the early 19th century, that or dropping and lightly rolling the soft dough in flour to shape. Carême, seeing that this was a delicate and time consuming process, knew there must be a better way. Pastry chefs had recently begun using small paper cones to pipe out creams for decorating, but Carême found this tedious and wasteful for larger preparations, having to work his way through so many paper cones to pipe out large batches of cookies. In a moment of genius, he decided to rig up a funnel so the thick batter or soft dough would easily and smoothly run out of the narrow opening, creating even bands of pastry.

In 1847, just 14 years after Carême’s death; one M. Aubriot, Parisian pastry chef at 390 Faubourg Saint Honoré, had the ingenuous idea to combine the little paper cone and Carême’s funnel to create a large, cone-shaped “funnel” from canvas fabric. He turned, no less, to that same M. Trottier we’ve met before, the Paris artisan who manufactured cake pans and other pastry utensils (see my post Gâteau Trois-Frères), to produce the small metal tips that nestle into the narrow open point of the pastry bag, allowing different sizes and shapes of opening and piping. And voilà the pastry bag - la poche à douille - was born.

Which brings both Carême and us to the éclair.

The éclair, like the quiche, is one of those iconic French specialities that seem to have been around forever, ingrained deep in the culture (and the psyche) of France’s culinary landscape. But the éclair is an early 19th century pastry that was rebaptized in the middle of the century. And it took several years for it to standardize into the éclair we find in boulangeries across France today.

We’ve already discussed the invention of the pâte à choux, a cross between a thick batter and a soft dough, cooked to dry out over the heat, that, when baked, creates those light-as-air puffs we call choux. From Pantarelli (or Pastarelli), known to many as Popelini, pastry chef to Catherine de Médicis in 1540 who created the pastry then known as popelin or pouplin (or poupelin…it does get rather confusing); to Tirolay, pastry chef to the Duke of Orléans, Louis Philippe II, who, 2 centuries later, renamed the pâte à popelins the pâte à chaud (hot dough), making his mark by dropping spoonfuls into boiling oil to create les pets de nonnes (nuns’ farts) or beignets soufflés (puffed donuts); to Avice, mentor to Carême, who used the dough to create le pain de la Mecque topped with pearl sugar, the smaller version now called chouquettes, and les Ramequins by folding in grated cheese, savory puffs we now know as gougères; to, of course Carême. Imagination and innovation creating new from the old. And the usual methods used by pastry chefs, from André Viard to Belon to Carême, was either to shape the dough into fingers using a spoon or by rolling the dough lightly in flour until the desired shape and size.

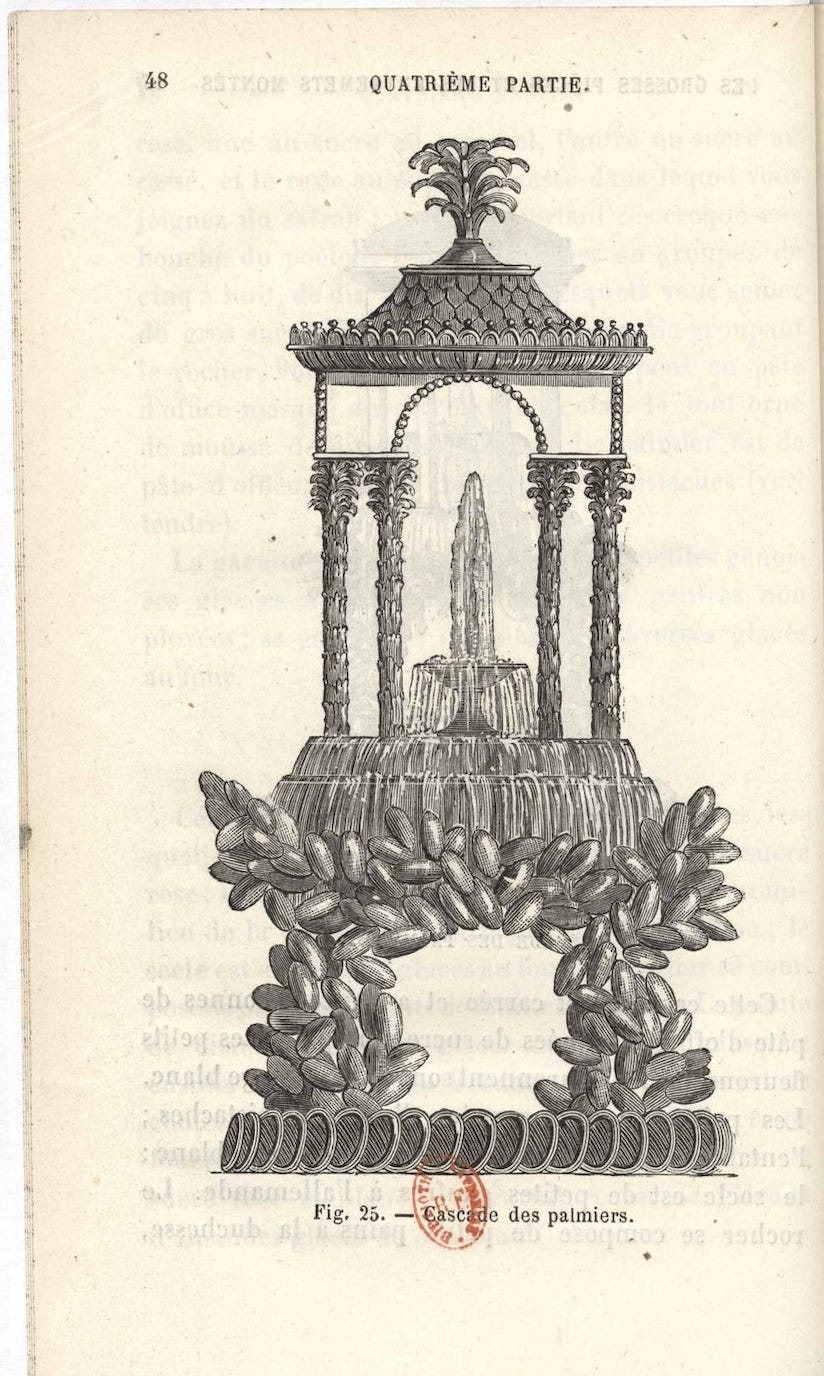

Carême, genius that he was, took the dough and created a vast number of variations on the usual round, dropped pastry, baked (Popelini) or fried (Tirolay), adding his own distinctive flourish by giving each creation and variation a different name depending upon the balance of ingredients, the filling, the topping, the size and the shape: les choux à la Mecque, à la Saint-Cloud, à la Vincennes, les gimblettes, les choux soufflés, and les pains à la duchesse. The last, the pains à la duchesse, were small, elongated “sticks” or fingers of choux dough.

In Le Pâtissier Royal Parisien, Carême’s 1815 cookbook, he fills the pains à la duchesse with apricot or peach jam or red currant jelly. The posthumous 1879 edition of this book, now titled Le Pâtissier National Parisien, in keeping up with the political times, has the elongated pains à la duchesse (curiously not changed to éclairs) filled with either jam or chocolate pastry cream, sometimes topped with a hard caramel coating. Carême also differentiates his dough recipe for pains à la duchesse, the future éclair, from the pâte à choux prepared for his other variations on this pastry by explaining that the pâte à choux used when making pains à la duchesse contains less butter, sugar, and flour than regular choux so, when baked, they puff up hollow in the center in order to fill this hollow interior with creams or marmalades.

So Carême brought his elongated sponge fingers vision to choux and called them pains à la duchesse, duchess breads or loaves, thought to be so called after Catherine de Médicis who was Duchess of Brittany at the time of the creation of the pâte à choux.

If in doubt about the transformation of the pain à la duchesse into the éclair, the great Jules Gouffé explains in his 1873 cookbook Le Livre de Pâtisserie: “Over the last twenty years or so, the name of these cakes (pains à la duchesse) has been changed: they are now known as éclairs.” Or Joseph Favre in his 1895 Dictionnaire Universel de Cuisine Pratique: Éclair, “previously called pains à la duchesse, small stick-shaped cakes made from choux pastry, filled with cream and iced.”

Trying to pinpoint the invention of the “éclair” and trying to understand who and why decided to change the pastry’s name means narrowing it down cookbook by cookbook. A tedious job, but someone has to do it…

In 1836, at least 2 noted cookbook authors were still calling them anything but éclairs, so we know this was still before someone decided to rename them, but the confusion of trying to differentiate similar pastries continued. M. Burnet was instructing the readers of his Dictionnaire de Cuisine et d’Économie, both professionals and amateurs (maitres et maitresses de maison) to shape choux and pouplins, made from pâte à la duchesse, pâte à choux, and pâte à pouplin, with a spoon. He differentiates his pâte à la duchesse and his pâte à choux by making the former with cream and the latter with water (I will explain this in my éclair recipe post). His pâte à pouplin is used to make one large puff which is spread inside with jam. Belon creates flavor variations, naming them accordingly petits pains à la duchesse, à la reine, à la paysanne, à la rose, d’anis, de marrons, followed by a mind boggling array of choux recipes in Le Pâtissier National et Universal of the same year. He doesn’t shape them using spoons, rather he tosses the dough in flour and shapes them by hand.

Elmé Francatelli, who trained under Carême then returned to his native London to work, called them Duchess loaves in his English language cookbook The Modern Cook. He instructs “These are made of the same kind of paste (pâte = dough) as the foregoing (petits-choux*); this must be laid out on the pastry slab, in small sizes the size of a pigeon’s egg, then rolled out with a little flour, in the form of a finger.” He brushes each with egg wash to give them a golden color in baking, then ices them by dusting them with sugar and heating to caramelize. Just before serving, the duchess loaves are split and filled with apricot jam and served piled up on a napkin in a pyramid shape. (*his note: “Pronounced by English cooks as ‘petty-shoes’”).

In the same year, 1845, les petits pains à la duchesse are mentioned in Les Classiques de la Table. And Le Comte Cousin de Courchamps still has recipes, separate recipes, for pâte à la duchesse, pâte à poupelin, pâte à choux, and pâte royale in his 1853 Dictionnaire Général de la Cuisine Française Ancienne et Moderne; he also rolls his dough in flour while shaping them into “little loaves” by hand.

And then suddenly they appear. And Gouffé was apparently right when he mentioned the timeline of this pastry. And it fairly coincides with the invention of the poche à douille.

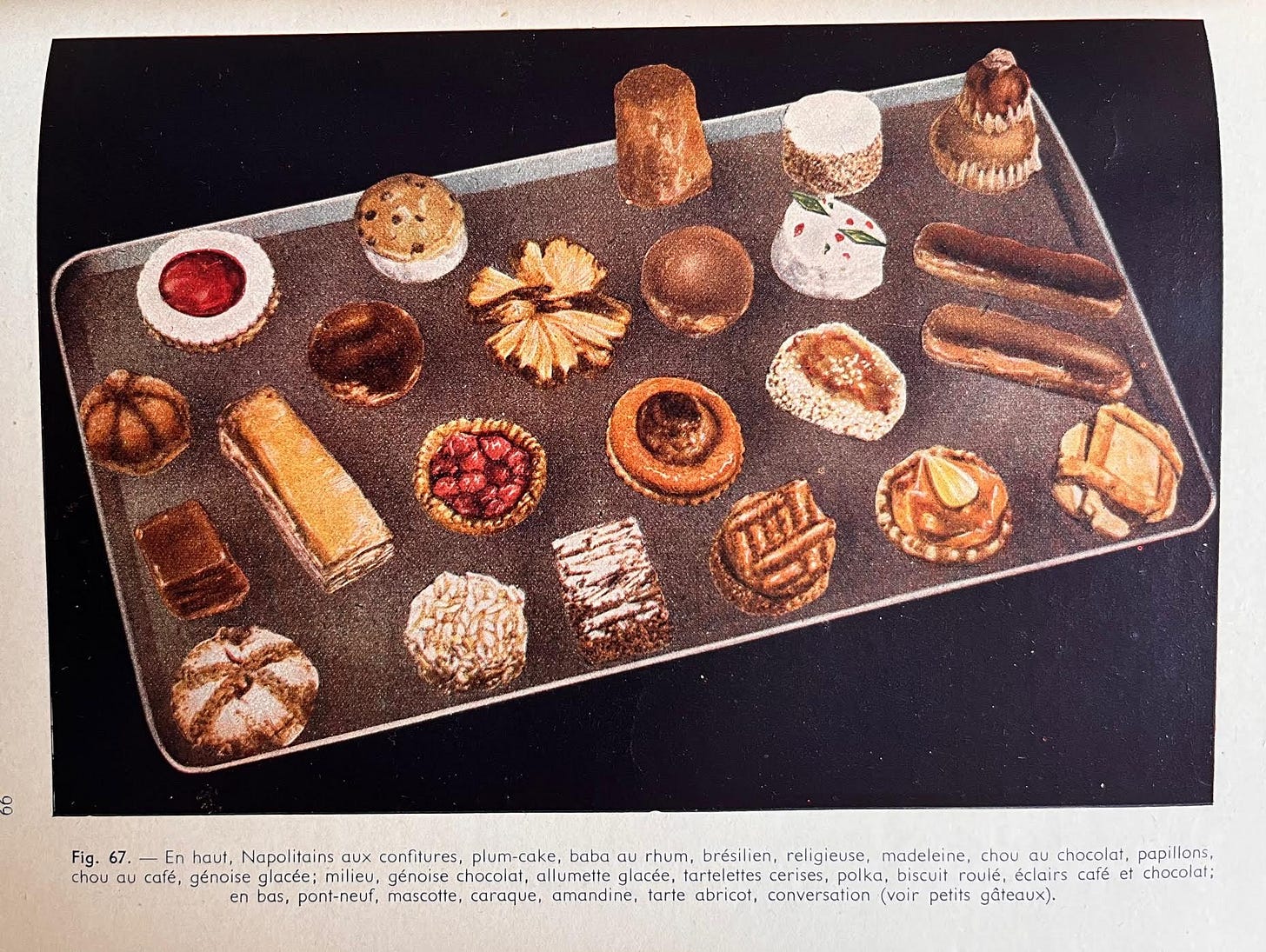

Louis Bailleux might be one of the first to have an actual recipe for the éclair in his 1856 Le Pâtissier Moderne, his recipe alongside those for choux grillés, pain de la Mecque, choux crème, pain duchesse, and choux panaché, now each made from the same choux pastry dough. And it is pretty well defined: using a poche garnie de sa douille, a pastry bag with its tip, he measures each éclair 7 cm long by 3 cm wide (3 inches by 1 inch); they are baked until light golden, slit horizontally and filled with either coffee or chocolate pastry cream and iced with, respectively, a coffee or chocolate glace à chaud (a shiny icing made from flavoring a sugar syrup and cooking until it will cool on the pastry to form a thin, crisp layer of icing). Bailleux separates the éclair clearly from the pain à la duchesse, which is now only filled with apricot marmalade, glazed with a hard caramel, then sprinkled with chopped/crushed pistachios.

The pastry will soon become familiar fare and standardized in cookbooks, the éclair now being a small, elongated choux only filled with either coffee or chocolate pastry cream and topped with the same flavor of icing. Arthur-Charles Bourdon’s éclair recipe in his 1874 La Pâtisserie Pour Tous only differs from Bailleux’ by brushing the surface of each éclair with melted apricot jam before icing while Bailleux uses red currant syrup for his, not only adding a bit of flavor but softening the crispy pastry, as well (something I’d not seen before nor after). Bourdon has just a single recipe for pâte à choux - choux dough - that he says is used for “many types of little cakes, such as: Choux grillés, Choux crème, Choux glacé, Pain de la Mecque, Éclairs, etc etc.” He includes a recipe for a duchesse instructing “With the choux dough, pipe out éclairs” which, along with round choux, he uses to line a Charlotte mold that is then filled with creams. He also includes a recipe for éclairs which he fills with a Saint-Honoré cream flavored with, yes, either coffee or chocolate.

Gouffé (Le Livre de Pâtisserie, 1873) also offers just a single pâte à choux recipe for croquembouches, pains à la duchesse, and éclairs. But while mentioning éclairs, his recipe is still headed pains à la duchesse au café and pains à la duchesse au chocolat, not éclairs. He simply adds a line at the end of the first of these 2 recipes explaining: “the assorted little pastries known as éclairs are made with crisp dough and filled only at the last minute.” He has a third variation filled with Chantilly (whipped cream) and garnished with sweetened strawberry purée.

Sophie Wattel calls éclairs “these excellent little dessert cakes” in 1886 (Les Cent Mille Recettes de la Bonne Cuisinière Bourgeoise à la Ville et à la Campagne) and again fills them only with either coffee or chocolate cream, topping them with more of the same. She does add the suggestion “for crunchy éclairs, dip in barley sugar and sprinkle with crushed pistachios, sugar grains or Angelica.” And while Pierre Quentin gives a recipe not for éclairs but for pains à la duchesse, he does mention éclairs one time in his cookbook La Pâtissière de la Campagne et de la Ville (also 1886) at the tail end of his recipe for a religieuse pâtissière, a type of simple cream tart, with “This cake can also be topped with either chocolate or coffee éclairs.”

It seems that chefs are still trying to get the hang of éclairs.

By the time our old friend Pierre Lacam publishes his Le Mémorial Historique et Géographique de la Pâtisserie in 1900, the name éclair was reserved for small “sticks” or fingers of choux and filled uniquely with coffee or chocolate pastry cream and glazed with coffee or chocolate icing. Every variation on les petits éclairs café et chocolat had its own unique name: les narcisses were filled with Chantilly and topped with slivered almonds and powdered sugar; les salammbôs were smaller éclairs filled with a kirsch or vanilla cream, the top caramelized and dotted with pistachios; les duchesses et les bâtons royaux are piped out longer than éclairs and filled with whipped Chantilly cream and caramelized; bâtons Jacob are 15 cm-long éclairs filled with vanilla whipped Chantilly cream, the top caramelized; and finally les éclairs à la Gounod were 6 cm-long choux fingers filled with a creamed chicken purée with diced ham and glazed with a sauce chaud-froid brune. And shortly after, in 1909, Emile Darenne and Emile Duval have a recipe for éclairs in Traité de Pâtisserie Moderne, which are filled with either coffee or chocolate pastry cream and iced in the same flavors, and duchesses, “the same procedure as the éclairs” but filled with vanilla cream and topped with a sugar glaze.

Which brings us to the name.

L’éclair.

In a very long, tightly written multi-definition entry of the word “éclair” covering half a page, one must look very hard and very carefully for the mere mention of “sorte de gâteau” or “type of cake” in Littré’s Dictionnaire de la Langue Française back in 1874, possibly the first dictionary to have a definition for the éclair as a pastry. According to the 1930 edition of Larousse du XXe Siècle, the éclair, this “elongated cake containing cream and with an iced top is so called because it is eaten very quickly to avoid spilling cream.”

Un éclair, a lightening bolt, “something that only lasts a moment,” according to Pierre Vincent”s 1892 Dictionnaire Illustré.

Works for me!

I hope one day I’ll stumble upon a text that lets me know who decided one day to change the name from pains à la duchesse to éclairs. And who decided that an éclair would strictly be limited to either coffee or chocolate. But I do know that today they can be found in bakeries across France almost uniquely (or primarily) in the 2 traditional flavors, coffee and chocolate. And really who needs anything else? Not me!

As Pierre Lacam wrote “choux pastry: today, under the pretext of 'saving eggs', less flour is used; the pastry swells less and the cream doesn't find room to be used in quantity. Despair of the ladies who eat two or three instead of one.”

Oh, I could easily eat 2 or 3.

I have decided, as my post is very long and I have several recipes to share - 2 different recipes for the pâte à choux, 3 different recipes for fillings, and 2 for glazes - to separate l’éclair into 2 separate posts. The recipes will follow this one very shortly!

Thank you for subscribing to Life’s a Feast by Jamie Schler where I share my recipes, mostly French traditional recipes, with their amusing origins, history, and anecdotes. I’m so glad that you’re here. You can support my work by sharing the link to my Substack with your friends, family, and your social media followers. If you would like to see my other book projects in the making, read my other essays, and participate in the discussions, please upgrade to a paid subscription.

What a wonderful post! Thank you. I so look forward to part 2.

You've done it again, Jamie! So appreciate you sharing your work like this!