The name “cake” (gâteau) probably derives from the extravagance with which they spoil (gâter) their children, distributing cake as a reward or gastronomic incentive.- Alexandre Dumas, Grand Dictionnaire de Cuisine, 1873

Trois-frères. Three brothers. Auguste, Arthur, and Narcisse, the Julien brothers were pretty revolutionary in the world of French pastry back in their day. Creative geniuses. “Relentless innovators,” according to Pierre Lacam in his book Le Glacier Classique et Artistique en France et en Italie, a sort of chatty history and who’s who of French pastry of the 19th century.

Les frères Julien, the 3 Julien brothers, created such confections as the savarin (and the savarin syrup, as famous and important as the cake itself, “a monument in the world of pastry,” as Lacam describes it), the moka, the cambacérès, the génoise à chaud, and the trois-frères, among a multitude of others, in their renowned Parisian pastry shop. P.-C. Dessolliers wrote in L’Art Culinaire, the professional bi-monthly magazine of “cuisine and table” from the Society of French Chefs, in January 1888:

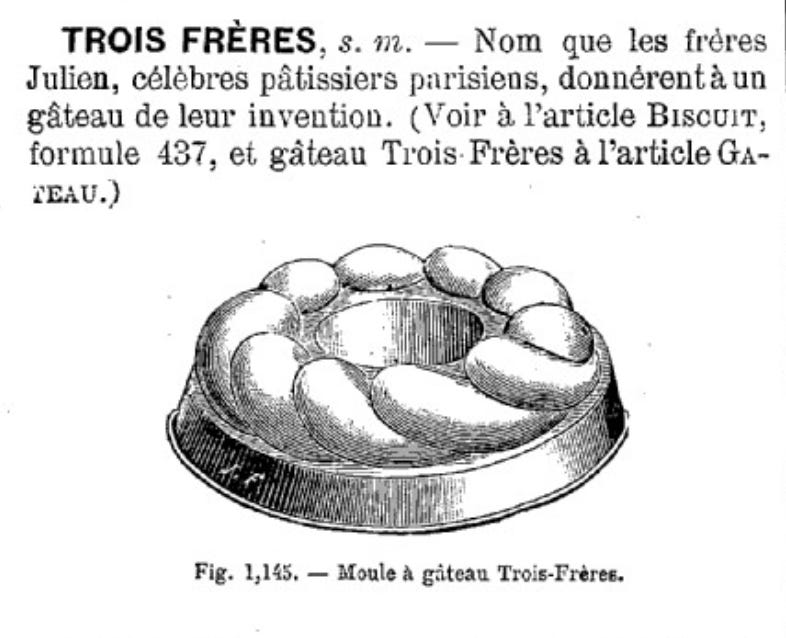

“It was in 1845 that M. Auguste Julien, the youngest of the three brothers, created this cake (the Savarin); happy with the success of his creation, some time later he composed a second cake which was named le Trois-Frères (the Three-Brothers); both of these cakes gave birth to a great emulation movement in pastry-making, not only by their indisputable quality, but also by their graceful and absolutely new shape; for this M. Trottier, the famous (cake and pastry) pan/mold-maker, understood Mr. Julien's ideas perfectly….”

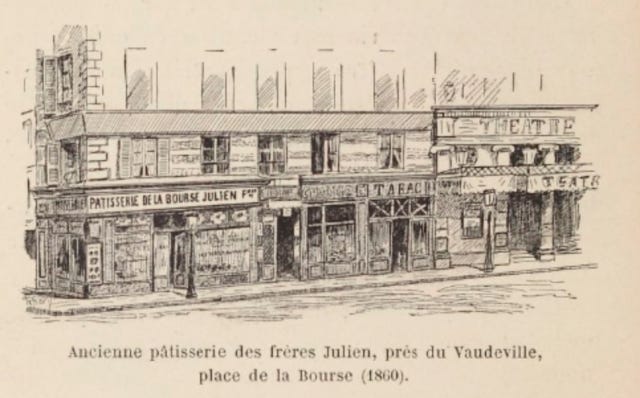

In 1844, two of the brothers, Auguste and Arthur, and their wives, two sisters, opened the family shop at 27, rue Vivienne on the corner of la rue Filles-Saint-Thomas, across from the Bourse, the Exchange, an ideal spot for maximum foot traffic, as they observed when choosing the location. La Pâtisserie de la Bourse. A few years later, in 1851, the youngest brother, Narcisse, joined them and from there they were unstoppable in their creativity. Driven by both a passion for innovation and an unparalleled business savvy, the Juliens began creating new cakes and pastries, giving each an unforgettable name, often a nod to “our greatest eaters” (Lacam): le (Brillat-)Savarin, le Talleyrand, le Richelieu, le Cambacérès, le Berchoux, le Cussy. They developed creams and syrups, as well, and were the first to soak an entire cake in syrup; they are responsible for a new way of caramelizing almonds, quickly baptized le pralin trois-frères. Clients lined up in front of the shop and down the street to taste the confections at the Pâtisserie de la Bourse. “During intermissions, crowds would leave the (neighboring) Théâtre de Vaudeville and cram into the Pâtisserie de la Bourse for cakes and pastries… succulent mouthfuls “à faire damner une sainte (that would damn a saint). It was a veritable orgy, a debauchery of pastries. The intermissions saved the plays." (Les entre’actes sauvaient les actes.)” (L’Étoile, 9 February 1874)

Their fame spread and the money rolled in, spurring on the brothers to even more creations. And to keeping their inventions and recipes closely guarded secrets. The “great emulation movement in pastry-making” spoken of by Lacam alluded to the fact that other pastry chefs around Paris, noticing the reason for the brothers’ success, began not only inventing their own pastries and giving those pastries fanciful names, hoping to grab some of the public’s attention and patronage, but attempting to reproduce the famed recipes of the Julien brothers themselves. Joseph Favre, our old friend, wrote in the Dictionnaire Universel de Cuisine Pratique (Universal Dictionary of Practical Cooking) in 1903:

“… this cake (the trois-frères), which owes all its success to the pan (mold) created by the Julien brothers, famous Parisian pastry-makers, has had several recipes, but the one that most closely resembles the original, if we consider taste is (here he indicates the recipe he shares in the dictionary)…These famous industrialists did not bequeath their secrets to us; as merchants above all, they were more concerned with making their fortunes than with popularizing the results of their research for the benefit of all. Nevertheless, we will continue to eat cakes as exquisite as those that contributed so greatly to their fortunes. Alas, that they were unable to take with them! May the earth be light to them.”

Quite tongue in cheek, Favre seems to resent the fact that the Julien brothers kept their recipes secret…to the grave.

Pierre Lacam also complained about the lack of generosity of the Julien brothers in sharing their methods and recipes, but goes on to explain the reason: the three hid recipes or kept parts or certain elements of recipes secret, recipes that were also both laborious and difficult to accomplish successfully, so no one could copy them and reproduce their cakes and pastries. He writes “This cake (the trois-frères) had an infinite number of recipes, but the real ones never left their establishment; at first the Juliens added 125 grams of ground almonds per pound (of batter)… the cake pan à trois-frères will outlast many others (other recipe variations) because of its practical use.” *sigh* thank heavens for the pan…

Not only did method and technique, the constant search for perfection, make their pastries more intriguing and most definitely original, but with many of their new cakes and pastries came a new shape, something that greatly added to each pastry’s renown, and the brothers’ fame. With these new recipes, they would design a new cake pan then produced by M. Trottier (they even filed for patents for these newly-shaped cake pans), from then on associated with, indistinguishable from the cake itself. And yet those unique pans became so well known that they began to be used for other desserts. Look through the cookbooks of the time and in dozens of other recipes you will find the instruction to use a “moule à gâteaux trois-frères” or a “moule à savarin” or the “moule à gorenflot”. According to Lacam, the brothers had Trottier make half a million of the trois-frères cake pans.

So let’s get to our recipe of the day. The gâteau trois-frères is a cake made with rice flour and melted butter folded into eggs that have been whisked or beaten with sugar, traditionally over a bain-marie or a source of heat, until lightened and thickened. The cake is flavored with either vanilla or marasquin, a liqueur prepared by sweetening maraschino brandy, made from a variety of bitter cherry. The cake is set on a sweet pastry base; it is then “abricoter” or brushed all over with strained and slightly reduced apricot jam and decorated with chopped praline almonds and candied angelica.

What’s so interesting is that the development of this cake, which happened over several years, is fairly well documented, as opposed to the invention of the technique for the extremely innovative (for its time) gâteau de Savoie. Auguste Julien, working for a time in Bordeaux for the famed pastry chef Lorsa, observed an Italian pastry chef whisking the batter for a cake much like the gâteau de Savoie in the style of the Italian’s home town Gênes, Genoa, over a low flame, an astounding new technique in pastry, actually considered a ridiculous folly (until it wasn’t and then it became all the rage). Auguste tried the technique, working on it until he succeeded in creating an excellent génoise, as he dubbed it to honor the man who showed him the technique, light and tender. He continued to develop and perfect the cake after returning to Paris where he worked first for Chiboust (Auguste also brought back what was to become the Saint-Honoré to Chiboust, made by Lorsa in Bordeaux as a Swiss flan) and then once he opened his own establishment. He first beat the eggs and sugar over a low flame to lighten and thicken the concoction, then added melted butter. As the fashion for using rice flour began to take hold (remember how the invention of potato flour was used to improve the gâteau de Savoie), he tried replacing the regular flour in his génoise with rice flour, creating an more intriguing cake with a unique texture.

He finally achieved the cake he was looking for, the right texture, the right flavor. At about the same time, his and Arthur’s younger brother, Narcisse, joined the family business and, in 1851, Auguste decided to honor the occasion by creating the gâteau trois-frères using the technique he had developed for the génoise.

As I’ve said, the Julien brothers never shared the recipe for this cake beyond one or two employees, and yet an estimate (or rather a “guesstimate” as my mom would say) for the recipe appeared in quite a number of 19th century cookbooks, all similar and yet all just different enough from each other. Pierre Lacam, who apparently had a proprietary obsession and great esteem for the Julien brothers finally wrote in his book Le mémorial historique et géographique de la pâtisserie, contenant 1,600 recettes de pâtisseries, glaces et liqueurs (The Historical and Geographical Guide to Pastry, containing 1,600 recipes for pastries, ice creams and liqueurs) in 1900 (which contradicts his own statement made a few hundred pages earlier in the same book - see the quote above):

“The Real Trois-Frères: almost all authors or others who write add ground hazelnuts or almonds to the three-brother cake. None of this exists. Le trois-frères has always been made, from its creation in 1849 to the present day: beat 200 grams sugar and 6 eggs over heat. Vanilla. Fold in (add with a spatula) 170 grams rice flour and 150 grams melted butter. Small quantities. Brush with apricot marmalade, and add squares of angelica and praline almonds (amandes pralinées à trois-frères).”

Lacam continues with his homage to the men, these three huge, imposing brothers with thick, bushy beards, whom he referred to as “the three primitive Gaulois” (“those handsome heads of our early Franks with their uncultivated beards, wearing Mexican caps in summer and red velvet caps in winter”):

“All the talk was about the Julien brothers and the Pâtisserie de la Bourse, especially in the provinces and abroad. The Julien brothers have left an indelible mark. Dumas père (the elder Alexandre Dumas) called them The Giants of Pastry (Les Géants de la Pâtisserie). Caricatures had taken hold of the Julien brothers as celebrities. They were depicted, among other things, as three bright red lobsters covered by a single toque (chef’s hat), a symbol of strength and courage. How many plays have been staged at the Vaudeville that featured their cakes!.. They were the first to innovate cake after cake; they are the ones who brought new inspiration and momentum to the world of pastry. The house had a reputation that no one in the pastry business has ever had, or ever will.”

Gâteaux Trois-Frères

Despite so few ingredients, the batter takes a bit of work - and a lot of muscle - to make, but what a gorgeous, creamy batter it is! This recipe makes 2 cakes in the traditional trois-frères cake pans, but try it in a Bundt pan, just keeping an eye on the baking time. I find this cake denser and slightly dryer than the gâteau de Savoie, but now that I have tested it, the next time I make it I will take it out of the oven sooner than I did this time, when the cake hasn’t browned as much. It’s an excellent cake to serve with coffee, but my team at the hotel, who loved it, suggested serving it filled with whipped cream and strawberries and I think it would be perfect!

My trois-frères cake pan is 9 inches (23 cm) in diameter with a 3 ¾ inch (9 cm) center tube/hole and is 2 ¼ inches (5 ½ cm) deep which held half the batter. For the other half I used my smaller 8-inch (20 cm) Bundt pan. Both pans have a nonstick surface.

10 tablespoons (150 grams) unsalted butter

6 large eggs

1 cup (200 grams) sugar

Large pinch salt

2 teaspoons vanilla or 2 tablespoons marasquin or amber rum

1 level cup + 3 level tablespoons (170 grams) rice flour

A jar of good quality apricot jam

To decorate: candied angelica or a candied fruit (I used strawberries) and coarsely chopped praline/candied almonds or peanuts

Begin by first gently melting the butter over a low flame and setting aside to cool.

Preheat the oven to 375°F (190°C). Butter 2 trois-frères cake pans or small Bundt pans or 1 regular Bundt pan.

Find a large, heatproof (Pyrex) glass mixing bowl and a deep pot that is large enough for the mixing bowl to sit comfortably nestled in the opening, leaving several inches between the bottom of the bowl and the bottom of the pot. You want to put about 2 inches water in the pot and the bottom of the mixing bowl should sit a few inches above the water. Have a whisk ready to go. Also have a hand mixer set up and ready to use.

Bring the 2 inches of water to the boil then turn down the heat so the water is not above a simmer. Break the 6 eggs into the mixing bowl and whisk to blend; whisk in the sugar and the large pinch of salt.

Place the bowl with the eggs and sugar over the barely simmering water and begin whisking. Whisk vigorously constantly, being careful not to splatter the mixture. Whisk constantly until the sugar dissolves and the mixture foams then turns opaque and increases in volume and thickens (see photos). This could take up to 20 minutes… you MUST whisk constantly so the eggs do not cook over the heat. Switch arms when you need to.

Remove the mixing bowl with the thickened mixture from the heat and begin the beat on medium-high heat using the electric hand mixer. Mix until it is doubled in volume, thick and creamy, and the batter forms a ribbon when the beaters are lifted. This will take several minutes. The batter will cool while you are beating.

Beat in the vanilla while you are beating the egg/sugar mixture with the electric hand mixer.

Add the rice flour in about “ additions: sift about a third of the flour over the thick eggs and sugar mixture and, using a spatula, fold the flour in… you do not want to fold too much so add another third of the flour before the first addition is completely folded in then do the same with the third and final addition of flour.

Add the cooled butter in about 2 additions, pouring the butter down the side of the mixing bowl and, again, adding each addition before the previous addition is completely folded in.

Once all of the flour and butter has been added, given the batter several good firm folds to finally make sure both are well blended into the batter.

Carefully pour the batter into the prepared pan or pans.

Bake in the preheated oven until risen and golden - mine baked in two pans for 15 or 20 minutes and it could have baked a few minutes less.

Remove from the oven, allow to cool in the pans for a few minutes before turning out of the pans onto racks to cool completely.

While the cake is cooling, very gently melt several tablespoons (I used about half a cup or so) apricot jam in a small saucepan just to warm and loosen. Strain out any chunks of fruit.

When the cake is cool, place on a serving plate and brush all over with the apricot marmalade. Decorate with candied fruit and praline/candied almonds or peanuts.

Thank you for subscribing to Life’s a Feast by Jamie Schler where I share my recipes, mostly French traditional recipes, with their amusing origins, history, and anecdotes. I’m so glad that you’re here. You can support my work by sharing the link to my Substack with your friends, family, and your social media followers. If you would like to see my other book projects in the making, read my other essays, and participate in the discussions, please upgrade to a paid subscription.

This looks lovely!

This posted at 3:55 am and I had just gotten up and it was a lovely way to start my day🤗