Who knows of a modest stew, To make a sovereign feast, Without the need To call it: Navarin - D. Bonnaud, Grands et Petits Cordons, 1923

As I sat and wondered what dish I could write about, the perfect spring dish as Easter approached, I hit on the navarin d’agneau, a stew starring the emblematic food of the season in France, lamb, and a panoply of colorful fresh spring vegetables. And as I had just written up the Marengo, an iconic French dish named after a great battle victory, I decided that I would do another. After all, I had heard and read multiple times, the navarin was named after the Franco-Anglo-Russian victory on October 20, 1827 over the Turkish and Egyptian navies at Navarin (Navarino), near Pylos, during the Greek War of Independence. The Battle of Navarin… lamb navarin. Perfect.

And that’s where it all started, my never-ending fall head first down the rabbit hole. And as they say in France: “un train peut en cacher un autre” - one train can hide another - a sign of warning as one approaches a railway crossing - in this case, one classic dish was indeed hiding another.

Like squeezing blood from a turnip, I couldn’t get enough. For weeks, I couldn’t stop researching as one discovery just let to another, deeper and farther into the stew. And so I dove in head first and have finally come up for air. Enough is enough, or at least for now. So here we have the navarin d’agneau. Part 1, of course.

On first glance, on wanting to believe the illustrious beginnings of such a beautiful and iconic dish, we find the story that makes sense. The day following the French victory at Navarin, Admiral de Rigny, commander of the French fleet, ordered a one-day improvement in the crew's diet as reward for their triumphant campaign. His ship’s cook decided to replace the usual rice in the day’s ration of mutton stew with vegetables, primarily turnips and potatoes. The crew went wild and such was the success of the dish that the Admiral himself tasted it. And loved it. Or so the story goes. Word spreads quickly in culinary circles in France (as we have seen in previous posts), that within 3 short years, this navarin stew appeared on the menus of Paris’ most prestigious restaurants and became all the rage.

Or so the story goes. And this is where it gets interesting. For the battle isn’t the one fought at Navarin (Navarino); rather the true Battle of Navarin is the one carried on over the course of the next two centuries among the culinary journalists, chroniclers, and cookbook authors of the day. About the origins of the name of this dish. And the ingredients that make it up.

Here’s where our old friend Joseph Favre of Marengo fame comes in. In Tome 3 of his 1895 Dictionnaire universel de cuisine pratique, Favre claims the word navarin is actually from the word navet (nes or naviel in old French dialects), navet, of course, being the French for turnip. Less exciting than a battle, right? Favre writes “Navarin from the word navets (nes or naviel) - the name once given to a stew in which turnips are added to tenderize the breast meat. Also a “ragout of kid (young goat or chevreau) or lamb (agneau). From this origin, it is now almost exclusively applied to mutton, but since Parmentier’s importation/cultivation of the tuber, turnips are more often than not replaced by potatoes, yet one continues to incorrectly refer to this dish as navarin. And this is why we sometimes find the antithetical Navarin aux pommes (de terre) on many restaurant menus. Consequently, there isn’t a navarin aux pommes (de terre) without turnips.” Unflinchingly resolute, our Joseph Favre. And a tad judgmental.

He then includes 2 versions of a navarin: the Navarin Primitif which is a pretty traditional recipe (either mutton or kid, with turnips and new onions) to which is added cider and pork lardons. Followed by a recipe for the classic Navarin de mouton (which, looking closely, is basically the same recipe with minor differences although using exclusively specific cuts of mutton) to which he adds the note: “If you would like to add potatoes, they should only be added in the same proportion as the turnips. If the turnips were completely omitted, the dish would be mutton stew with potatoes instead of Navarin.” Favre was nothing if not persistent.

So no Battle of Navarin. But going back a bit further, closer to the date the dish was said to have been created, the idea that navarin is tied to the addition of turnips to a classic mutton stew has already taken root. So to speak.

Hector France’s 1847 Dictionnaire de la Langue Verte (langue verte defined as “archaisms, neologisms, foreign idioms, local dialect, and slang”) has 2 entries for navarin, the first being “navet (turnip); thieves' slang” and the second being “mutton stew which contains turnips”. Alfred Delvau has pretty much the same definitions in his Dictionnaire de la langue verte. Argots parisiens comparés (Comparative Parisian slang) of 1866, a few years later: “navet (turnip) in thieves’ slang” (given for an object of little value) and “a mutton stew with potatoes and turnips - in the slang of boulevard restaurants (the boulevards of Paris) - it's a new name for a dish known for a very long time.”

Delvau’s definition of navarin as a mutton stew containing potatoes and turnips once and for all officialized the name for this dish. Just 2 years later, Baron Brisse, French gastronome and culinary journalist and author, declares in his 366 Menus of Baron Brisse (New edition of 365 menus, revised, corrected and expanded with a gastronomic calendar and recipes for all the dishes featured on the menus) in the heading of his recipe for navarin de mouton: “this is the new name given to the classic haricot de mouton.”

And now we’re getting somewhere.

Brisse gives no recipe for the navarin de mouton, but does for an haricot de mouton which, curiously, contains no turnips. Absolutely not a one. It’s simply a rack of mutton cubed and browned in butter; a roux is made with the addition of flour, broth is added along with a few potatoes, a bouquet garni, thyme, bay leaf, garlic, and parsley, salt, pepper, nutmeg; the stew is then simmered over low heat, degreased, and served.

So what is this dish “known for a long time” that became the navarin in the 19th century? The dish that Alexandre Dumas describes as “this plebeian stew, a dish that is so old that no one knows how far back it was made and eaten” in his 1873 Grand Dictionnaire de Cuisine? Haricot de mouton.

Well, we do know that the haricot de mouton does at least go as far back as the Middle Ages. The great Taillevent, Guillaume Tirel, has an haricoq de mouton in his medieval cookbook Le Viandier, one of the period’s earliest cookbooks (thought to be written anonymously in about the year 1300, later published in the second half of the 14th by Taillevant). This is the earliest recorded recipe of an haricot de mouton. His recipe is simply mutton meat from the breast which is first grilled then cut into pieces and placed in a pot with onions, ginger, cinnamon, other spices, and verjuice. He has a second recipe called herison de mouton - listed in the index as also being an haricot - in which the mutton is cut into pieces, cooked in lard with onion, to which, once cooked, beef broth, wine, verjuice, sage, mastic, hyssop, and saffron are added, the stew then boiled until cooked. The other great cookbook dating back to the Middle Ages, the Le Ménagier de Paris written in 1393 offers an hericot de mouton (his own spelling variation is haricot); pieces of lamb or mutton are parboiled then fried in lard, minced onions are added, deglazed with beef broth, mace, parsley, sage, hyssop, all boiled together.

From this we deduce, confirmed over time by a multitude of sources, that haricot refers to a stew or ragoût, specifically one that uses mutton. The word “haricot” itself has nothing to do with the word bean, today’s definition of the French word haricot; the word haricot apparently wasn’t attributed to the legume until about 1625 or so, and might have even come from the name for this stew which, at the time, often contained beans. The word haricot most likely comes from the old French verb “haligoter" ou “harigoter” meaning to shred or to tear to pieces. It was necessary to shred, cut, or tear to pieces very tough, lesser cuts of meat (now stewing meat) which were then simmered for a long time in a stew in order for those cuts of meat to be tender enough to eat.

Molière mentions an haricot in his 1668 play L’Avare, The Miser; a bon haricot bien gras (a hearty, fatty stew) is recommended as a meal because “we must have those things of which we don’t eat much but which fills one up with very little.” This plays into the idea that an haricot is a hearty dish, a frugal dish of economical (cheap) ingredients worthy of a miser. But does it follow that the haricot was a poor man’s dish, a peasant stew? While Antoine Furetière’s 1690 Dictionnaire universel, contenant généralement tous les mots françois tant vieux que modernes (Universal dictionary, generally containing all old and modern French words) defines haricot as “a mince made from large pieces of mutton or veal boiled with chestnuts, turnips, etc.” And the 1771 Dictionnaire universel françois et latin says practically the same - “a stew made with mutton and turnips” - we don’t quite get where this stew fits in the culinary scheme of things. Until we start checking cookbooks.

The fact that both Le Viandier and the Le Ménagier de Paris, 2 cookbooks written for the upper classes, the bourgeoisie and their cooks, contain recipes for this stew made apparently with cheap cuts of meat which are then long simmered, 2 signs that traditionally indicate a peasant dish, we can assume that the dish was something other than what it appeared. As we head into later centuries, we also see recipes for the haricot in a variety of cookbooks written for a select audience of chefs who create food for the elite and the comfortable. So not a peasant or lower class dish.

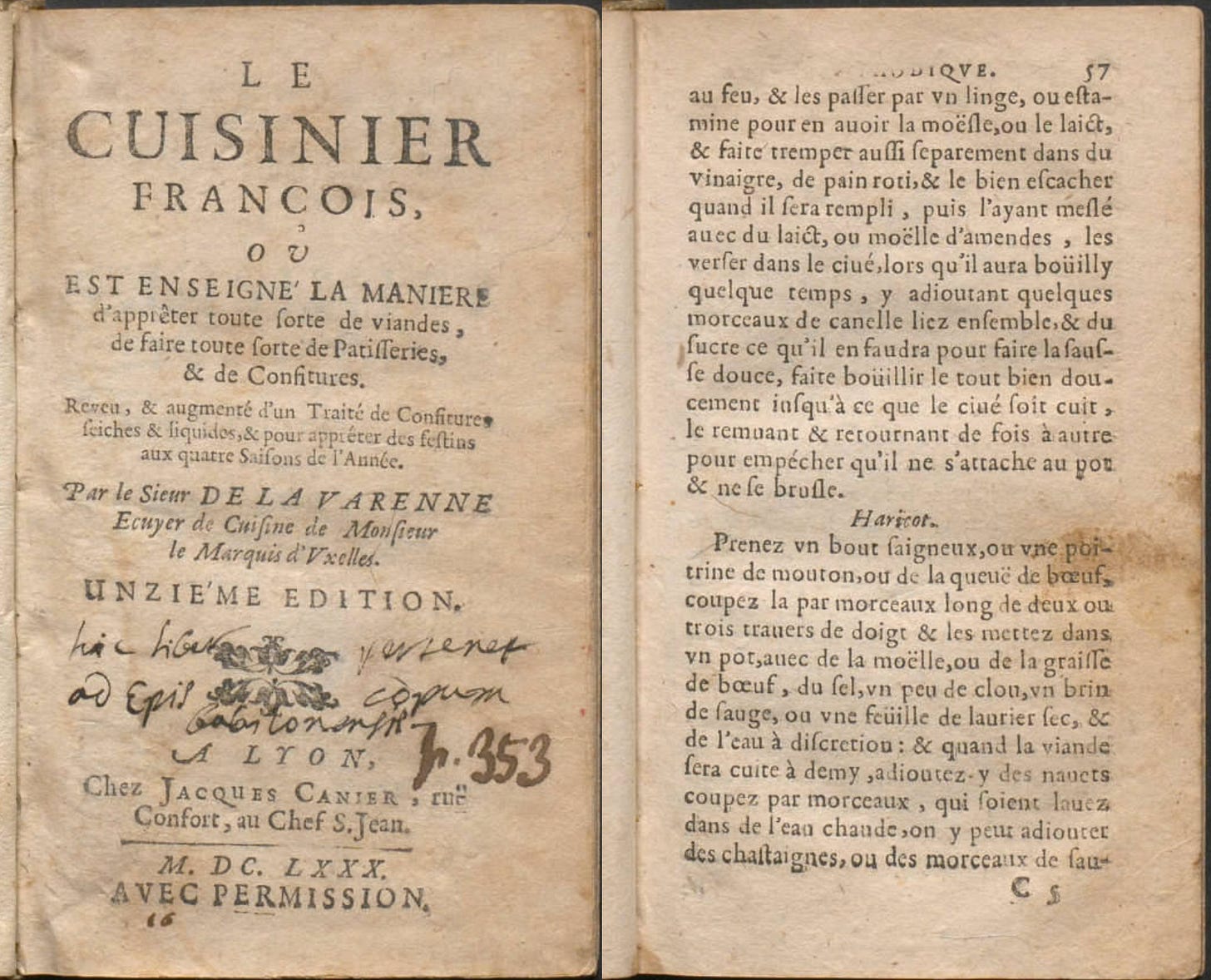

La Varenne doesn’t have an haricot in his Le Cuisinier François of 1651 but does have a ragoût of mutton shoulder prepared much in the manner of both Le Ménagier and Le Viandier. As the end of the century approaches, he ups his ragoût, now calling it haricot, in his 1680 edition, cooking either mutton breast meat or beef tail with marrow or beef fat and a nice variety of seasonings, including sage, cloves, and bay leaf. He then adds turnips cut into pieces, chestnuts, pieces of sausage, a couple of slices of stale bread soaked in vinegar, and finally suggesting that if one wants to add a bit of sweetness to the stew, one can add prunes and raisins. François Massialot has a selection of dishes he calls haricot in his Le Cuisinier Roïal et Bourgeois in 1705, one using duck, others featuring sturgeon, chops, even pike with turnips, as well as one made with macreuse or duck which is first cooked over embers then placed in a pot, seasoned, and cooked with turnips. The 1750 Les Dons de Comus by François Marin has an haricot made with hare, cooked with lots of fresh herbs, onions, and, yes, turnips. Served with a touch of vinegar and grilled bread for garnish.

The haricot is still very much in style through the 17th and into the 18th centuries. Curiously, these chefs are preparing the stews with different types of meats and fish, yet the one ingredient most have in common is the turnip. So I’m now leaning towards the haricot being.a stew in which the turnip is the starring vegetable, and the haricot de mouton is the popular version in which the meat called for is mutton.

Then we have Joseph Menon’s 1739 Nouveau Traité de Cuisine, “a book for anyone who is involved in ordering, serving, or cooking all kinds of new and fashionable stews following each season”. And there you have it. A fashionable stew. Menon also published Les Soupers de la Cour (Court Dinners) in 1755, a cookbook written “pour servir les meilleurs tables suivant les quatre saisons.” (To serve the best tables following the four seasons.) Recipes to prepare for the best tables. And in each book, Menon includes recipes for haricots.

Menon’s 1739 Haricot de mouton is made with rack of mutton which is cut into chops, braised with broth, then cooked with bacon, bouquet garni, salt and pepper. Turnips are trimmed and shaped into almond-shaped ovals then sautéed in lard without coloring, drained, and then simmered in broth until tender. The meat is served garnished with the turnips. He also has a recipe for Collet de mouton au navets which is exactly the same recipe as his haricot but written slightly differently and using a different cut of meat - the collet or neck of mutton. His 1755 haricot de mouton is rendered more complex and interesting, quite possibly because his book was written for the chefs of the Court. He’s using mutton breast meat cut into pieces, or the rack of lamb cut into chops; these are then cooked in broth with parsley, chives or spring onions, garlic, cloves, thyme, bay, basil, salt and pepper; while the meat is cooking, the turnips are trimmed and shaped then blanched in boiling water. The turnips are then simmered in a little jus and a little of the cooking liquid from the meat which has been strained; the turnips are done when pale (blond) and tender. The meat is arranged on a platter and served garnished with the turnips.

André Viard’s several editions (1817, 1822, and 1844) of Le Cuisinier Royal is the first to have 2 recipes for the haricot, separating them into one more rustic and one more sophisticated, an Haricot de Poitrine de Mouton followed by Haricot de Mouton à la Bourgeoise. The simple haricot places rounds of onion in the bottom of a pot (very rustic); chunks of meat are placed on top of the onions, with 2 carrots, bay leaves, thyme, and a large glass of broth; this is cooked until the broth is reduced to a caramelized glaze. More broth or water is added with salt, the stew is simmered for 2 hours. When the meat is cooked, it’s removed from the pot and deboned; the liquid is strained. Turnips are sliced into sticks and sautéd in butter; flour is then added to make a roux when the strained cooking liquid is added with a pinch of sugar. When the turnips are cooked, the meat is added to the pot and cooked until the sauce is reduced “à son point” (most likely until reduced to a nice sauce, about half an hour). One begins the Haricot à la Bourgeoise by making a blond roux with butter and flour then adding the meat and cooking until the meat is browned (a quarter hour); hot water is then added and the stew is cooked until the liquid comes to a boil. He then instructs to skim the liquid, add salt, pepper, parsley, chives, thyme and bay leaves and an onion pricked with 2 cloves. In another pan, the turnips are browned in butter then added to the stew with a pinch of sugar. When ready to serve, the fat is skimmed off the surface and the bouquet garni and onion are removed and discarded.

And finally, we round out our haricot in 1856 with the Nouveau manuel de la cuisinière bourgeoise et économique par un ancient Cordon Bleu - with turnips being the only added vegetable to the mutton which has been cooked in a pan until browned; the turnips are cooked separately in the mutton fat which has been transferred to a clean pan. The turnips are removed from the pan and flour is then added to make a roux with the fat; the lamb is then added to the roux with water, salt, pepper, bouquet garni, cloves, 2 onions, bay, and the turnips. The meat and the turnips are then simmered until cooked through. What’s important to note is the subtitle of this book: The best ways to make excellent food at very low cost. A former Cordon Bleu, indicating someone with an upper class chef’s training, writing a book of bourgeois cooking, again, dishes normally prepared for the upper class, is “providing an essential service to society's largest class” by recreating bourgeois dishes “without spending too much money”. From this we can conclude that the haricot de mouton was indeed considered a refined dish for a sophisticated table, even as it is made with ingredients normally found in a more frugal cuisine, lesser cuts of mutton, potatoes, and turnips.

He hoped there would be stew for dinner, turnips and carrots and bruised potatoes and fat mutton pieces to be ladled out in thick peppered flour-fattened sauce. Stuff it into you, his belly counseled him. - James Joyce

When I started my research for this post, I had the idea that the navarin would be a rather straightforward story, that I would get this researched and written up easily and quickly. This turned out to be rather simplistic of me. I should have known better; after working on this Substack for more than a year I have learned that I never know what unexpected places my research will take me. I was going to write up the history of the navarin d’agneau then share a recipe for a navarin d’agneau printanier, the best-known version of this classic dish. After the first 3 weeks of reading 7 centuries of cookbooks, dictionaries, and texts, I realized that this topic needed to be broken into 2 posts with 2 recipes: a simple, rustic navarin d’agneau based on the old haricot de mouton, the navarin made when fresh, young spring vegetables are not available. The second, well, we’ll get to that in the next post.

I’m not crazy about turnips so for this first recipe I chose a simple, rustic navarin that one begins to see in cookbooks of the late 19th century, lamb (no longer mutton) accompanied only with potatoes and small onions. Urbain Dubois has a recipe for a Navarin aux Oignons in his 1888 cookbook Nouvelle Cuisine Bourgeoise pour la ville et la campagne in which parboiled chunks of mutton breast are cooked with 2 or 3 dozen pre-browned pearl onions, a handful of chopped raw potatoes, salt, pepper, bouquet garni, and broth… until the meat is cooked and tender and the sauce reduced to half. I much prefer pearl or new onions to turnips. Interestingly, Auguste Escoffier’s 1934 Ma Cuisine has a recipe for navarin ou ragout de mouton containing no turnips, only small onions and potatoes; his navarin printanier does include turnips.

Navarin d’agneau aux oignons

2.2 pounds (1 kilo) stewing lamb - the best for this is boneless shoulder

1 large yellow onion, trimmed, peeled, halved, thinly sliced

2 or 3 medium carrots, trimmed peeled, halved lengthwise then cut into ¾- or 1-inch chunks

2 small turnips, trimmed, peeled, quartered, optional (personally, I don’t like them)

5 garlic cloves, trimmed, peeled, sliced in half or mashed

12 new onions or 16 to 18 pearl onions, trimmed and peeled

Potatoes for 4 people - I used about 10 small ratte (fingerling) potatoes - you can use about 4 medium-sized potatoes (use a variety that stays firm when cooked through)

Vegetable oil

Salt and pepper

3 teaspoons tomato paste

3 tablespoons (30 grams) flour

⅔ cup (150 ml) dry white wine, a pinot gris or chardonnay work fine

A bouquet garni or a few branches of fresh thyme and a bay leaf

Fresh flat leaf parsley

Water or half water, half meat stock

If glazing the onions, you’ll need a few tablespoons butter, maybe about 5 (75 grams) and up to a couple of tablespoons granulated sugar, white or brown.

Prepare the lamb by cutting off any excess fat and cutting the lamb into even chunks, about 2-inches large.

Heat a couple of tablespoons of vegetable oil in a large sauteuse or Dutch oven on high or medium-high heat. When the oil is very hot and starting to sizzle (you can check by flicking in a few drops of water into the pot), add the lamb in one layer - you can do this in one or two batches; the lamb should sizzle and steam. Salt and pepper the meat generously (I salt and pepper the meat on both sides, the second time once I turn the chunks). Without letting the lamb stick to the bottom of the pan, let the pieces brown well, almost caramelized, before turning the pieces. Or stir the meat around constantly, letting the meat brown on all sides.

Once the chunks of meat are browned, add the sliced onion, the carrot chunks, the garlic cloves, and the turnips, if adding. (If you browned the lamb in two batches, add all the lamb back to the pot). Stir to combine.

Add the tomato paste to the meat and vegetables, salt and pepper again, and stir to blend in the tomato paste.

Add the flour to the pot and stir quickly to evenly distribute the flour and evenly coat the meat; stirring constantly, cook for a few minutes.

Once the flour has “melted” into the meat and vegetables, add the white wine, scraping up the bits stuck to the bottom of the pot. Stirring constantly, allow the wine to cook for a minute or two; it will evaporate slightly and thicken with the flour.

Add the bouquet garni or the thyme and bay; add water or water and stock (I added a few spoons of powdered veal stock) to just cover all the ingredients. Bring to the boil then lower to a simmer, cover, and cook for 1 hour. (I think it best to check every now and then and stir the navarin, scraping the bottom of the pan).

While the navarin is cooking, peel the potatoes, rinse, and, if using larger potatoes, cut them into large chunks. Drop them immediately into a bowl of cold water to keep them from discoloring.

Trim and peel the onions if you haven’t already; if using larger new onions and you want to cook them separately in the butter and sugar, you can slice them in half, if you like.

At the end of the hour of cooking, add the potatoes to the navarin, pushing them underneath the surface of the sauce. Add a little bit more water if needed. You can add a couple tablespoons of chopped parsley, if you like. Cook the navarin for an additional 40 minutes, only longer if the potatoes are not cooked and tender to the center. (Again, I think it best to check every now and then and stir the navarin, scraping the bottom of the pan).

Melt some butter in a large skillet or sauteuse, then add a tablespoon or 2 of granulated white or brown sugar - I use brown granulated (cassonade, demerara, turbinado), NOT packing brown sugar. Once it’s all melted, add the onions; if using larger new onions like I did, be careful as they may fall apart when cooked so turn them carefully to cook on both sides. Add just a little bit of water, about a quarter cup. The liquid will evaporate as the onions cook.

Cook the onions until soft and cooked through. Using a slotted spoon, carefully remove them from the pan and any remaining liquid and transfer to a bowl.

If you prefer not to cook the onions this way, add them to the navarin about 15 minutes or so before the end of cooking.

Once the navarin is cooked and the sauce is the desired thickness - mine was perfect just having added water for the first hour of simmering although you can continue cooking to reduce it a bit more - you can transfer it to a large serving bowl if you like though I prefer serving it directly from the pot - top with the cooked onions and some chopped fresh parsley.

Thank you for subscribing to Life’s a Feast by Jamie Schler where I share my recipes, mostly French traditional recipes, with their amusing origins, history, and anecdotes. I’m so glad that you’re here. You can support my work by sharing the link to my Substack with your friends, family, and your social media followers. If you would like to see my other book projects in the making, read my other essays, and participate in the discussions, please upgrade to a paid subscription.

As always, many thanks for another enlightening post, Jamie! As an aside, I find it interesting how much in common some standard French dishes share, between for instance Boeuf Bourgignon, Coq au Vin, and Navarin d'Agneau. Some differences of course, but so much in common too!

Jamie, this looks delicious, and I must try it out. However, I'll add at least the specified amount of turnips, as my wife and I love them. As an old dear family friend used to say, "That's why they make chocolate AND vanilla, honey." Her exact words, which I remember her by. (Well, that and her cheating at cards.)