I don't like spinach, and I'm glad I don't, because if I did, I'd eat it, and since I loathe it, it would be infinitely unpleasant for me. - Henry Monnier as Monsieur Prudhomme

“It's a very tasty herb or plant used on all kinds of tables. It keeps the belly free, soothes coughs, tempers acidity in the chest, and is good for bilious stomachs.”

Thus did Joseph Menon describe spinach in 1757 in Cuisine et Office de Santé. Alongside the usual recipes for spinach with cream, for meatless or fast days, and with ham, bread, meat jus and coulis, for days one could eat meat, and simply with fried bread as an entremets, side dish or starter, he also includes a recipe for tourte aux épinards, sweet spinach tart, in his cookbooks.

But let’s back up a bit and start from the beginning.

Spinachiis, spinacia, spanachia, spynoches, espinarde, espinace, espinoche, espinars, espinard, épinard…spinach. Since it’s arrival in the south of Spain from the Arab world around the year 1000, slowly making it’s way up and around the European continent, it’s name altering here and there as time passed, as it meandered through different languages, spinach finally arrived in France in the 13th century. But it was Catherine de Medicis who popularized spinach in the 16th century, giving it that royal kiss necessary to make it more attractive to - and desired by - the Court, the upper classes, and finally the population as a whole. By this time, the plant itself had lost its spininess, from whence its name (spina or épine meaning spiny because early spinach had thick, prickly leaves), the leaves becoming larger, rounder, and more delicate, thus adding to its appeal.

Espinard, as spelled by Antoine Furetière in the 1690 edition of his Dictionnaire Universel, is defined as “an herb that is good to eat, especially useful during Lent. According to some, spinach (espinars) is a kind of arrowroot. In old French, they were called espinoches. Some people believe they were given this name because they came from Spain, and thus should be called espanars. But it seems more likely that their spiny seed is why they are named as they are. Spinach,” he continues, “are eaten fricasseed in butter, put in pastry, and made into spinach pies.”

Catherine de Medicis and her entourage of chefs had a huge influence on French cuisine, bringing with them recipes, ingredients, and cooking and baking techniques from her native Italy upon her marriage to the future Henri II in 1533. She adored spinach and ate it in dishes both savory and sweet, spinach in cream as well as sweet boulettes. But while we can give her credit for introducing many foods to France, spinach was already appearing in cookbooks well before Catherine arrived. And let’s not forget, these cookbooks were written by high-end chefs for other chefs working in high-end kitchens. Meaning that Catherine was not the first noble or aristocrat to happily find spinach on their dining table.

Both Guillaume Tirel, known as Taillevent, and Albertano da Brescia included recipes for spinach tarts in their cookbooks, respectively, Le Viandier, published in France around 1300, and Le Ménagier de Paris from 1393. Both combine spinach (espinoches and at times espinars) with parsley, mint, chard, lettuce, marjoram, and basil, all finely chopped, with (meat) juice, one egg of a large pheasant, powdered ginger, cinnamon, pepper, salt, and grated “fine” cheese. This herb filling is baked in a piecrust. Maître Chiquart expounds for several paragraphs on the preparation and use of a simple spinach purée to feed the sick, but he also suggests adding spinach leaves to his parmesan tart, a popular dish back in the day, in his book Du Fait de Cuisine of 1420.

“The Parisians know how useful spinach (espinars ou espinoches) is as food during Lent,” wrote Charles Estienne and Jean Liébault in their 1564 L'Agriculture et Maison Rustique, “and they use it in various ways for their banquets: now they fricassee it with butter and verjuice; now they conserve it a little with butter in earthenware jars; now they make pies and many other ways. The use of spinach is good for those whose voice or breathing is impeded and who cough often, especially if in the morning one sips a spinach broth cooked with fresh butter, or sweet almond oil, they loosen the stomach; its juice is used against scorpion and spider bites, either drunk or applied externally.” Spinach continues to appear in the popular cookbooks of the day, and while prepared in much the same way, the recipes are evolving and modernizing with the times. The Livre Fort Excellent, 1542, mixes blanched spinach with fried onions, a little pea purée, and almond milk; the author also has spinach in a mixed greens soup. Pierre de la Varenne adds cream and nutmeg to his spinach that has been simmered with salt, pepper, a spring onion and an onion stuck with cloves. “Some boil them in water,” he writes in 1651 in Le Cuisinier François, "but they aren’t as good, even if you're going to dress them the same way.”

While purées and other savory dishes were obviously popular, the sweet spinach tart or tourte is what fascinates me. While spinach had found its way into savory tarts before, the 16th century sees a sudden flurry of spinach being used in sweet pastries. “One must pick the most delicate before winter, and they are excellent in pastry,” asserts Nicolas de Bonnefons in his celebrated Les Délices de la Compagne in 1654. François Pierre de La Varenne’s épinards en tourte in his 1654 Le Vray Cuisinier is blended with melted butter, sugar, a dash of salt, and “le poids d’un maquaron d’amandes pilées,” the weight of a crushed almond macaron. La Varenne puts the sweet, almondy spinach filling in a pastry crust and bakes it, then serving it dusted with sugar, the rim decorated with candied lemon peel. 2 years later, Pierre de Lune offers a tourte d’éspinars in Le Cuisinier, cooking his spinach in white wine until “all the liquid has been consumed.” He then flavors his drunken greens with sugar, cinnamon, candied lemon peel, a little salt, 2 crushed macarons, and a little butter. His is a 2-crust tourte, the pastry placed atop the filling either in one piece or in lattice strips.

We see one of our first sweet spinach tourtes back in 1450 in Maestro Martino’s Libro di Arte Coquinaria (Book of the Art of Cooking). And it sounds scrumptious, in all the glory of medieval cooking in its wildly over-the-top combination of flavors and seasonings. Spinach was chopped together with parsley and marjoram, the herbs then fried in “good oil”. The cooked greens were blended with mashed dates and raisins, ground almonds, rose water, and fatty fish broth (possibly for the gelatine qualities). To this he added pine nuts, whole raisins, cinnamon, ginger, saffron, the whole thickened with cornflour or pike eggs. This filling was placed in a pastry crust and topped with lasagne sheets, sprinkled with sugar and rose water, and baked.

2 centuries later, sweet spinach pies are still being made, albeit rather simpler. François Massialot’s 1698 tourte d’epinars in Le Cuisinier Roïal et Bourgeois is the same as Pierre de Lune’s above, and by his 1722 Le Nouveau Cuisinier Royal et Bourgeois, Massialot has moved his filling to a puff pastry crust as well as turning it into rissoles, little individual fried hand pies. Joseph Menon’s 1739 version (Nouveau Traité de la Cuisine) is even simpler, his blanched spinach is sautéed in butter and sugar then mixed with cream, lime zest, and “grilled” orange flower. He is also making a lattice-topped puff pastry tart.

Pierre Joseph Buc’hoz, lawyer, doctor, botanist, naturalist, ornithologist, entomologist, physician - yes, they did that back then - and author of L’Art de Préparer les Alimens, Suivant les Différens Peuple de la Terre (The Art of Preparing Different Foods, According to the Different Peoples of the Planet), makes what sounds like a delicious, rich crème d’épinards with butter, ground almonds, a little lime, 3 or 4 bitter almond biscuits, sugar, cream, milk, egg yolks, all placed in a pie dish, topped with pastry, and baked until the cream is absorbed. “This dish,” he states, “is good for one’s health.” His tourte d’épinards is flavored with candied lime peel, sugar, and butter. “This dish is quite light, although it is in the form of a pie.” The spinach filling in his fried rissoles d’épinards, those little hand or individual pies, is flavored with sugar and orange flower water, lime zest, and crushed bitter almond macarons. Once fried, they are dusted with sugar and caramelized. “This food is extremely light,” he assures his readers.

The great Alexandre Dumas also included a recipe for rissoles d’épinards in his Grand Dictionnaire de Cuisine in 1873, and his are, again, as now seems to be the go-to, flavored as the others, a little lime zest, 2 bitter almond biscuits, sugar, orange flower water. And fresh butter. They are fried, then dusted with sugar which is also caramelized with a hot iron. The blanched spinach for his tourte d’épinards is flavored only with chopped candied peel, sugar, and butter, placed in a puff pastry crust, his lattice and decorative work with the rest of the puff pastry atop the filling is a bit more elaborate for a much simpler filling.

“Spinach, say the good folk, is the health of the body, like watercress, the cleanser of the stomach, like prunes, and nature's benefit as reverence for speaking, against colic. I don't know what to make of its decongestant virtues, which are particularly precious in this month, when we live too close to the fire and stuff ourselves with heavy foods to warm our abdomens. Spinach on the vine is all too often bitter and tough: it seems that the cook has watered it with her tears. But creamed spinach...is a smooth, tender delight. It's no longer an accompaniment to a roast, but a dish in its own right, and can rival the most delicate of all.” - 3 January 1937 Nouveauté : modes, ouvrages, variétés, roman

I turned to André Viard/Viart and his 1844 edition of Le Cuisinier Royal for inspiration for my recipe today. His version of the tourte aux épinards is a more interesting and, in my opinion, a more tempting version of the sweet spinach tart. While most of the other chefs have established that ground almonds - and, in extension, ground almond macarons - are the perfect flavor pairing with spinach, Viard goes one step further and blends his with a thick, creamy frangipane. Frangipane is a blend of pastry cream and almond cream, and while Viard’s is a simple pastry cream into which he folds finely ground almonds and almond macarons, flavoring it with a bit of orange flower praline, I chose to make a true frangipane for mine. But why spinach? you’re asking. Viard, while not including a distinct recipe for his tourte in his earlier version of 1817, he does explain in his section on frangipane when suggesting replacing the almonds with pistachios: “As it doesn’t have enough color, you'll put in a little spinach green, don't use macaroons or orange blossom, but three bitter almonds and sugar.”

Earlier versions of the tourte aux épinards are definitely spinach tarts, in which the green vegetable is the main ingredient and star of the pastry, and yet Viard wants us to believe that it is added primarily for the rich green color. And yet, he seems to have changed his mind in his later edition, adding butter-and-nutmeg sautéed spinach to the filling in a stand-alone recipe, and yet not giving a precise quantity of the vegetable. As I developed my own recipe based on his, adding 14 ounces (400 grams) of tender baby spinach leaves to the frangipane, I knew that this was actually an extraordinary way to prepare, serve, and eat spinach, which is so healthy for body and mind. Spinach is one of those vegetables that one either loves or loathes; while one can certainly, I will admit, sense a faint hint of spinach as one eats the tart, it is a surprising and surprisingly good dessert. So a great way to eat your spinach whether you like it or not.

As Grimod de La Reynière so aptly wrote in the Almanach des Gourmands in the January 1803 issue:

“Spinach ranks first in this category (the vegetables still available in our kitchens in January), because of the ease with which it can be obtained fresh for eight or nine months of the year. Although this vegetable is very common, it is no less the despair of avarice and the despair of industry, because its preparation is as expensive as it is difficult, especially to make it appear in all its glory. Spinach is worth little on its own, and is a wax-virgin, susceptible to all impressions; but in the hands of a skilled man, it can acquire great value. A dish of spinach alone has made a cook famous. Spinach, the healthiest of vegetables and suitable for all stomachs, can be cooked in (meat) juice, butter, cream or coulis; it is used to make soups, pies, rissoles, creams, etc.; it is the accompaniment to more than one distinguished dish... In short, it is the resource of the poor man's table, just as it is the glory of the rich man's: everything depends on the hands through which it passes.”

Tarte aux épinards - Sweet spinach tart

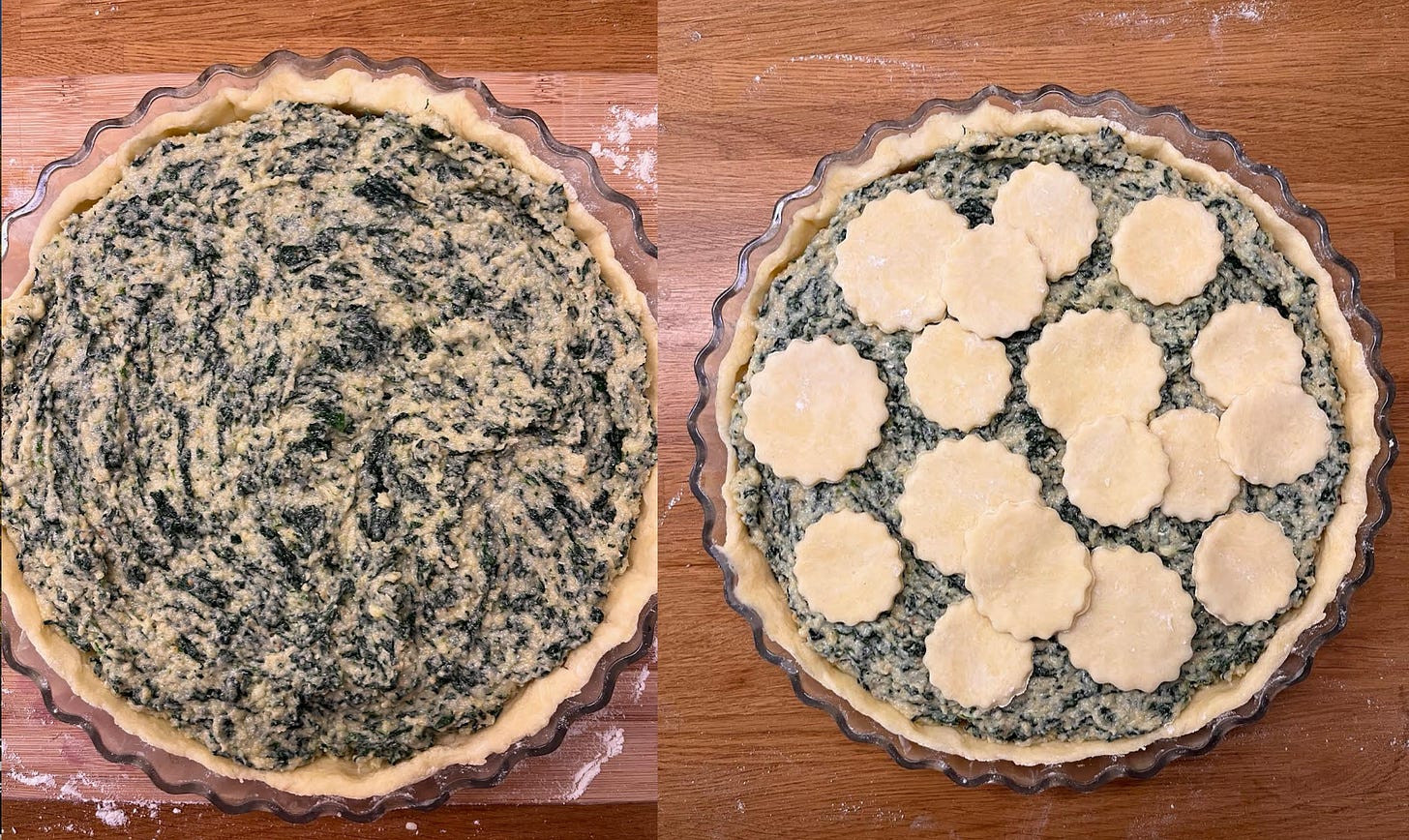

This tourte or tart has gone out of fashion, but it is really worth rediscovering. It is fairly simple to make, but there are several steps that, all together, take some time to make, so plan accordingly. Feel free to use a bit less spinach the first time you make it if you’re nervous about using spinach in a sweet pastry. Viard recommended to “place one or more cut-out puff pastry flowers on top of your frangipane.” Which, as you can see, I did, with my shortcrust dough in place of the more common lattice. Pretty, right?

Shortcrust (pâte brisée) or puff pastry (pâte feuilletée) for a 2-crust pie

Frangipane - a mixture of one part pastry cream (crème pâtissière) and two parts almond cream (crème d’amandes) - recipes below

14 ounces (400 grams) tender baby spinach leaves

1 egg yolk + 1 teaspoon cold water blended well together for the egg wash

If making a shortcrust (pâte brisée) - which I did, and it was perfect for this tourte - I followed this pastry crust recipe, simply doubling it for a 2-crust tourte (I did not quite double the salt). Prepare the dough, shape into a ball, wrap in plastic wrap, and refrigerate until ready to roll out.

Pastry Cream - Crème Pâtissière

2 large egg yolks

2 tablespoons + 2 teaspoons (35 grams) granulated white sugar, divided

Small pinch salt

1 tablespoon flour

1 tablespoon cornstarch

⅔ cup (165 ml) milk (whole milk only, half whole + half low-fat, or low-fat only)

Almond Cream - Crème d’Amandes

1 ½ cups + 1 tablespoon (5.5 ounces / 155 grams) finely ground almonds

1 ½ cups + 2 tablespoons (5.5 oz / 155 grams) powdered sugar*, sifted after measuring

10 ½ tablespoons (155 grams) unsalted butter, softened

1 tablespoon Amaretto, optional but will accentuate the almond flavor

1 teaspoon vanilla

*To measure powdered sugar; stir up the sugar in the bag or box to aerate; lightly spoon the sugar into the measuring cup until mounded over the rim; using a flat blade, level the sugar at the rim of the cup. Sift after measuring.

Prepare the Frangipane (Pastry Cream and Almond Cream):

Preheat the oven to 325°F (160°C). Spread the finely ground almonds on a large baking sheet.

Begin by preparing the Pastry Cream: Vigorously whisk the egg yolks with half the sugar and the salt in a large mixing bowl until blended, smooth, and thickened. Sift the flour and cornstarch together into the bowl and whisk until a thick, smooth, lump-free paste is formed. Heat the milk with the rest of the sugar in a medium pot over medium-low heat until the first bubbles appear. Slowly pour the hot milk into the egg mixture in a stream while whisking vigorously to prevent the eggs from cooking. Once the hot milk has been whisked into the eggs, pour it all back into the pot and return to the heat. Whisking continuously, cook the pastry cream over medium-low to medium heat until it comes to the boil and then allow it to boil, whisking nonstop, for 1 to 2 minutes until the pastry cream is thick and luxuriously fluid. Remove from the heat and immediately scrape the pastry cream into a small heatproof/Pyrex bowl or mixing cup, cover with plastic wrap, pressing the plastic directly onto the surface of the pastry cream, and refrigerate until chilled.

Prepare the Almond Cream: Slide the ground almonds into the preheated oven and allow them to toast for 10 minutes (check occasionally to make sure they don’t burn); remove them from the oven and scrape into a bowl or platter and allow to cool. Once the ground almonds have cooled, place the butter in a pot over low heat and when the butter is only half melted, pour into a heatproof/Pyrex mixing bowl, whisk in the powdered sugar until smooth and then whisk in the roasted ground almonds, the Amaretto, and the vanilla.

Prepare the Frangipane: Remove the now cooled/chilled pastry cream from the refrigerator and whisk or beat into the almond cream until well blended, smooth, and creamy. Cover with plastic wrap and place in the refrigerator to cool while you prepare the spinach.

Prepare the spinach: Pick over the spinach, pinching off and discarding all of the stems. Rinse the leaves well to remove any dirt. Shake off the leaves - without drying them off! - and place in a large pot; the water left clinging to the leaves will steam the spinach. Place the pot on a medium or medium-high heat, cover the pot, and steam for several minutes, stirring occasionally, until all of the leaves are wilted. Drain in a colander and allow to cool. Once the spinach is cooled, squeeze the spinach to remove as much water as possible; this is most easily done by wrapping it all tightly in a clean (and old) kitchen towel and squeezing. Chop the spinach as finely as possible.

Heat the oven to 400°F (200°C).

Butter the bottom and sides of a 10-inch (25 or 26-cm) pie dish (I prefer glass/Pyrex).

Remove the pastry dough from the refrigerator. On a floured work surface (and flouring the surface of the dough), roll out about ⅔ of the dough about an inch (2 cm) or a bit more larger than the bottom of the pie plate; lift and place the round of dough into the buttered pie dish and fit it in well, bottom, corners, and up the sides to the rim. Trim off any excess dough above the rim of the pie dish. Using a fork, lightly prick the bottom of the dough all over.

Prepare the tourte: remove the frangipane from the refrigerator and fold the chopped spinach into the frangipane until the spinach is evenly and well dispersed into the cream and the cream is smooth.

Spread the filling evenly into the prepared pie crust.

On a floured surface, roll out the remaining dough and cut out flower shapes using fluted cookie cutters; or you can slice into long strips and make a more traditional lattice crust for the top of the tourte. Lay the pastry flowers on the frangipane. Brush each flower (or the lattice strips) lightly with the egg wash.

Bake in the preheated oven for about 45 minutes, keeping careful watch during the last 10 minutes. The filling should be puffed and look a bit crispy; when gently pressed it won’t feel raw but it might not feel completely set - don’t worry as it will set as it cools. The pastry will be a deep golden, the top crust shiny from the egg wash. Carefully lift up the tart (if using a Pyrex/glass baking dish), and the bottom and sides of the crust will be a nice deep golden.

Remove from the oven to a cooling rack and allow to cool completely to room temperature before slicing.

Thank you for reading and subscribing to my Substack Life’s a Feast. Please leave a comment, like and share the post…these are all simple ways you can support my writing and help build this very cool community. If you would like to further support my work and recipes, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. It’s truly appreciated.

And to think—I fancied myself quite the connoisseur of herbal lore. Yet here is spinach, humbly reclining on the plate, concealing a talent for thwarting scorpions and spiders alike.

How delightfully dramatic! One almost wishes to be bitten, just to see it in action.

Thank you, once again, for such an enchanting experience!

Fascinating! Almonds and spinach- who knew? (Well, the French obviously knew.) The recipe looks slightly complicated to me - likely it is not to most who bake regularly- but I might try it when I get ambitious.

But what an amazing history. I didn’t realize spinach had medicinal qualities (and I thought I knew that of most herbs/vegetables). “Its juice is used against scorpion and spider bites, either drunk or applied externally.” Hopefully I won’t have to try this.

Thanks for another delightful culinary trip through history!