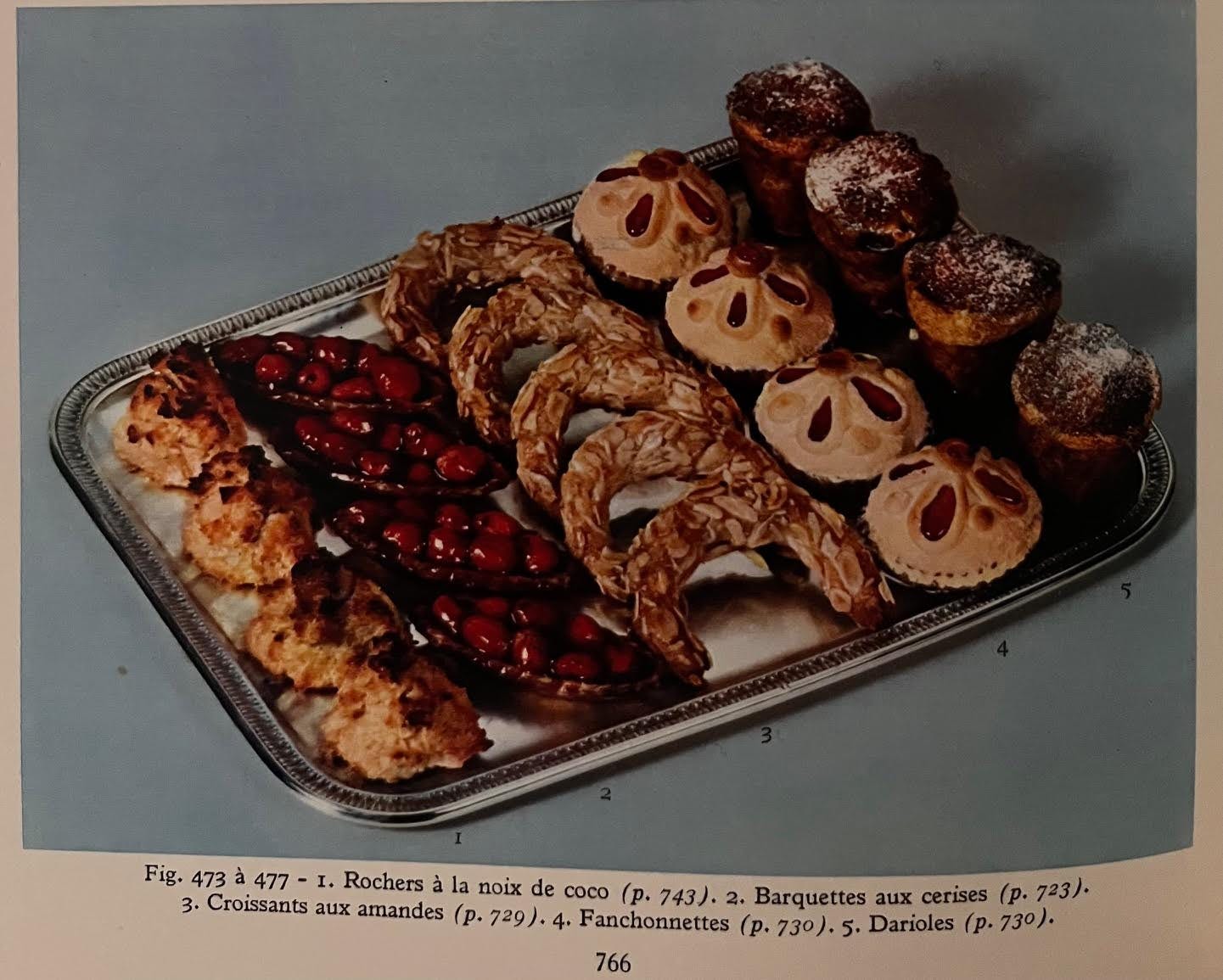

Darioles

Better than flan.

There are limits to self-indulgence, none to restraint. – Mahatma Gandhi

Premier mets : Venoison de sanglier en souppe, Sabourot de poussins, Boussac de lièvres, Oyes à la trayson. / Second mets : Cygnes, Hérons, Faisans, Paons. Trimolecte de perdris. / Tiers mets : Most Jehan, Pasté de merles, Pijons au sucre. / Quart mets : Dariolles de cresme fricts, Pastés de poires. / Quint metz : Amandes, Noysilles, Poires crues, Jonchées. *

"Alas, who now knows of these strange dishes (of the Middle Ages), their particular sauces, these artful mixtures? Who knows the name of the cook Taillevent, head chef to the poor king of Bourges? In Chinon, Charles VII was content with a roasted mutton tail and a meager chicken for his most luxurious dinner; but after Joan of Arc's death and the departure of the English, sauces of all kinds were needed; and galimafrée (stews), darioles, and poivrades (sharp sauces) were invented.” This from Le Pêle-Mêle weekly humor newspaper in 1918 couldn’t be clearer. Who still remembers the dishes that were popular back in the day, dishes that might have eventually faded out of culinary existence?

* The above menu was created by the famed chef Guillaume Tirel, better known as Taillevent, for the grand banquet at the château de Gombervaux in 1367 for King Charles V and Jean I, Duc de Lorraine celebrating the signing of the Treaty of Vaucouleurs, which guaranteed the eastern borders of the Kingdom of France. A royal feast that consisted of a highly seasoned and spiced wild boar soup; chicks sautéed in onions and lard with chicken livers, ginger, and verjuice, the sauce thickened with bread; rabbit pieces roasted then cooked in beef broth, wine, and aromatic spices; goose cooked in beef broth with cinnamon, cloves, and mustard; swans, herons, pheasants, peacocks, and partridge stew ; roasted capons served with a sweetened milk sauce seasoned with ginger, saffron, and finely chopped fresh herbs; blackbird pie; pigeons in sugar; cream darioles; pears in pastry; almonds, hazelnuts, pears, and cream cheeses. We dive into Taillevent’s cookbook to discover what Sabourot, Boussac, Most Jehan, Trimolecte, and Darioles are, because, as was so aptly stated in Le Pêle-Mêle so many centuries later, we are hard put to know just what these strange dishes are.

And we stop at darioles. No swans, herons, peacocks, or wild boar this! Darioles, then dariolles de cresme fricts or darioles de cresme d’amandes, were small, individual cream tarts.

“In the 15th century, pastry-making had already been perfected and gained in importance,” wrote Vanaise in La Pâtisserie Française Illustrée in 1946. “The variety of doughnuts multiplied... gohières (gougères), which were cheese flans, popelins (filled choux), darioles, a kind of banded or ribbed tart, i.e. cut in different directions by strips of pastry, were made…” Darioles were already quite popular by the opening of the 15th century, enough so as to make it onto Taillevent’s illustrious menu. And their acclaim was such that it might have been one of the most cited French pastries of its time and for time to come: from François Villon’s 15th century poems (“Darioles, whole tarts, he tasted everything but ate not one thing that he had touched.”), François Rabelais’ Pantagruel, Livre IV, Chapitre XI, 1532 (“These rocks and marbles are beautiful. I don’t speak ill of them but the darioles from Amiens are more to my taste.”), the extraordinary La Grande Danse Macabre des Hommes et des Femmes, 1641 (“I've drawn innumerable baths, For the friends and gossips, Where were quince pastes Eaten darioles, gougères, Tartes and made a thousand grand desserts…”), and Guillaume Budés 1550 analysis of Thomas More’s Utopia in which he adds descriptions where More does not (“They never dine or sup without music; the meals always start with music as a healthy way to aid digestion, which work prevents, and there is always dessert, pears, apples, and other fruits, tartes and galettes, and darioles… they indulge themselves in all such pleasures as are attended with no inconvenience.”)

And Edmond Rostand’s Cyrano de Bergerac:

Cyrano de Bergerac, Edmond Rostand, 1897

Cyrano: Are you fond of sweet things?

La Duègne: Ay, I could eat myself sick on them!

Cyrano: Good. See you these two sonnets of Monsieur Beuserade. . .

La Duègne, piteously: Hey…?

Cyrano: …which I fill for you with darioles.

La Duègne, changing demeanor: Ha!

The dariole was already well-mentioned in cookbooks before and then during the 15th century; whether or not because, as Pierre Lacam wrote centuries later, “The choice of pastries was limited during this period.” Albertano da Brescia listed darioles de cresmes quite often as a dessert in many of his menus, more than a dozen times, in his 1393 Le Ménagier de Paris, yet offers no recipe, almost as if already well known. Taillevent’s late 14th century Le Viandier includes the same recipe for darioles de cresme d’amandes found in the 1495 publication Le Livre de Taillevent: "Soit broyés amandes, et non guère passés, et la cresmes fort fricte au beurre, et largement sucre dedens” or “ground almonds, not much sieved, cream cooked with egg yolks and butter, and sweetened.” The English cookbook, Fourme of Cury, published in 1390, has a recipe for daryols calling for “cream of cow milk” and almonds, sugar and saffron. It is baked in a “coffyn” or coffin, the common term for a pastry crust, “II ynche depe. Bake it wel and sue it forth.” It appeared in the 2 famed Italian (Latin) cookbooks of the period, as well, Libro de Arte Coquinaria by Maestro Martino da Como in 1460 and Platynae de Honesta Volvptate et Valitvdine, published around 1475, referred to in both as diriola.

In 1547, Jean Bonfons also adds saffron to his almond cream filling, specifying it is for the color, in Le Grant Cuysinier de Toute Cuysine and a few years later, cinnamon and saffron are both added to “good cream or fatty milk” in Livre Fort Excellent de Cuysine Tresutille & Proffitable. The author of the latter book explains how to add eggs or bread to thicken the cream if one wants to make “flantz” or flans; from the beginning, one finds, darioles and flans are made with the same batter, the same recipe, except that flan batter is thickened with either bread or (more) flour.

By 1654, Nicolas de Bonnefons gives a single recipe for both a dariole and flan filling in his book Les Délices de la Campagne, the two recipes identical except the flan filling (indeed) has more flour; he is now adding both flour and eggs to thicken the milk, and using no flavorings at all. François Pierre de La Varenne finally gives this pastry the space in a cookbook it deserves, giving it a full 2 ½ pages in Le Pâstissier François in 1653. His recipe is very modern for the time, giving not only precise quantities of ingredients but the utensils to use, as well. His filling is simply flour, eggs, milk, and only enough salt as needed “because it requires very little”; “and if you don't have cow's milk or any other animal milk, one can use almond milk.” He lines a single pie dish with pastry, making one large tart. Once the dariole is baked, it is taken out of the oven, a slit or hole is made in the filling, and a large piece of unsalted butter and a fair amount of sugar are put into this hole. The dariole is then returned to the oven until the butter and sugar are melted. “It takes about a good half an hour to bake a dariole.” And once it is baked, you can dust the top of the dariole with butter, sugar, and rose water.

The popularity of the dariole continued unabated through the next couple of centuries, appearing in most pastry books and many cookbooks even as the number of new pastries rose by leaps and bounds. Eggs, flour, milk, sugar, “this pastry seems even healthier, as all of its ingredients are healthy by nature” claimed Pierre-Joseph Buc’hoz in L’Art de Préparer des Alimens in 1787.

And then comes Carême. Carême, known for his extravagant pastry creations and bold innovations, riffs on the cream dariole by offering darioles soufflées aux macarons amers or à cédrat, darioles au café, au café Moka, and à l’orange in Le Pâtissier Parisien of 1815. He even suggests adding “the zest of a fine citron, a bigarade, a lemon or an orange, in short, all the fragrances you can think of.” From the Middle Ages through the Napoleonic Era, the dariole remained consistently a simple cream tartlet scented with rose water, almonds, or cinnamon. Carême saw that it could be flavored in so many new ways, and gave it that impetus, no matter, as we will see, how short-lived.

But one new thing appears: while other chefs are baking darioles in small, copper timbale molds for petits pâtés au jus, Carême bakes his darioles in petites moules à darioles, baptizing the mold after the tartlet And the size and shape of this pastry come to define the pastry itself. Just as Carême takes a medieval treat and modernizes it, the moule à dariole - dariole mold - itself will very quickly take on a life of its own.

The size and shape of the dariole has long been defined more or less clearly, since early days. “Large Dariole is made in a tourtière (large pie dish) or a piece of pie-shaped pastry (free-form), give it about two good fingerbreadths of edge. This same batter is used to make small Darioles; sometimes as wide as the palm of the hand with finger-high edges; sometimes in pots two fingers high and with the bottom as wide as a small ecu (coin).” Noël Chomel gives these rather precise dimensions of a dariole in the Dictionnaire Oeconomique in 1767, not much different than that in the Fourme of Cury, “2 inches deep”. François Marin uses a single pie dough to make several small crusts “two fingers high” in Les Dons de Comus, 1758. Carême prepares small “charteuses” “in small timbales in the style of dariole molds, but these must be two inches high and the same width, or three small inches in all senses.” Small, individual pastries, wider at the top, narrower at the bottom, 2 or 3-inch tall tarts that can fit into the palm of one’s hand like a cannelé or a baba. Or an ecu.

We’ve seen pastries come…and go. We’ve also seen baking pans or molds created especially for a new cake or pastry, the pan taking on the name of the dessert and then being used to make other things, think Savarin, Baba, cannelé, Trois-Frères. Once moules à darioles came into being, they are found dotted throughout cookbooks, used in a whole panoply of sweet confections. But not only! We find moules à darioles used for everything from macaroni to eggs to meat stuffing, sweet or savory soufflés, seasoned fish purée or vegetables, to “aspic in which is suspended a beautiful round of foie gras. “The dariole disappeared around 1856 or thereabouts,” states Pierre Lacam in Le glacier classique et artistique en France et en Italie (1893). Indeed, he may very well be referring to Louis Bailleux’ Le Pâtissier Moderne published in 1856, and he was almost right. While the grand pastry chefs of the 19th century, Bailleux, Jules Gouffé, Pierre Quentin, Gustave Garlin, and chefs such as André Viard and Alexandre Dumas, include the original cream tarts, darioles, in their lists of recipes, the pastry begins to fade away. And yet, the moule à dariole does not, in much the same way that the gâteau Trois-Frères was replaced by newer, more popular cakes yet the pan lived on, so has the dariole.

Dariole and talmouse went on the kings' table. Progress has put them aside. - Pierre Lacam and Antoine Charabout

By the early 20th century, we are hard put to find darioles in a recipe book, other than the grand classics of historical and traditional dishes, such as L’Art Culinaire Moderne, 1935, La Cuisine Moderne Illustrée, 1939, L’Art Culinaire Français, 1950. Auguste Escoffier includes quite a number of recipes in both Le Guide Culinaire (1921) and Ma Cuisine (1934) using moules à darioles yet not a dariole recipe in sight.

A small cake now forgotten and wrongly neglected. It used to be made by the dozen. - L’Art Culinaire Français

The definition of dariole in Prosper Montagne’s Larousse Gastronomique (1938) begins: “Currently, this word designates a kind of small cylinder-shaped mold. In former times, a dariole was what one called a pastry.” Pierre Lacam lamented this pastry that he thought “better than flan” explaining “(the) dariole and talmouse were served on the kings' table. Progress has put them aside.” Sometimes progress is not for the best. Not in pastry…

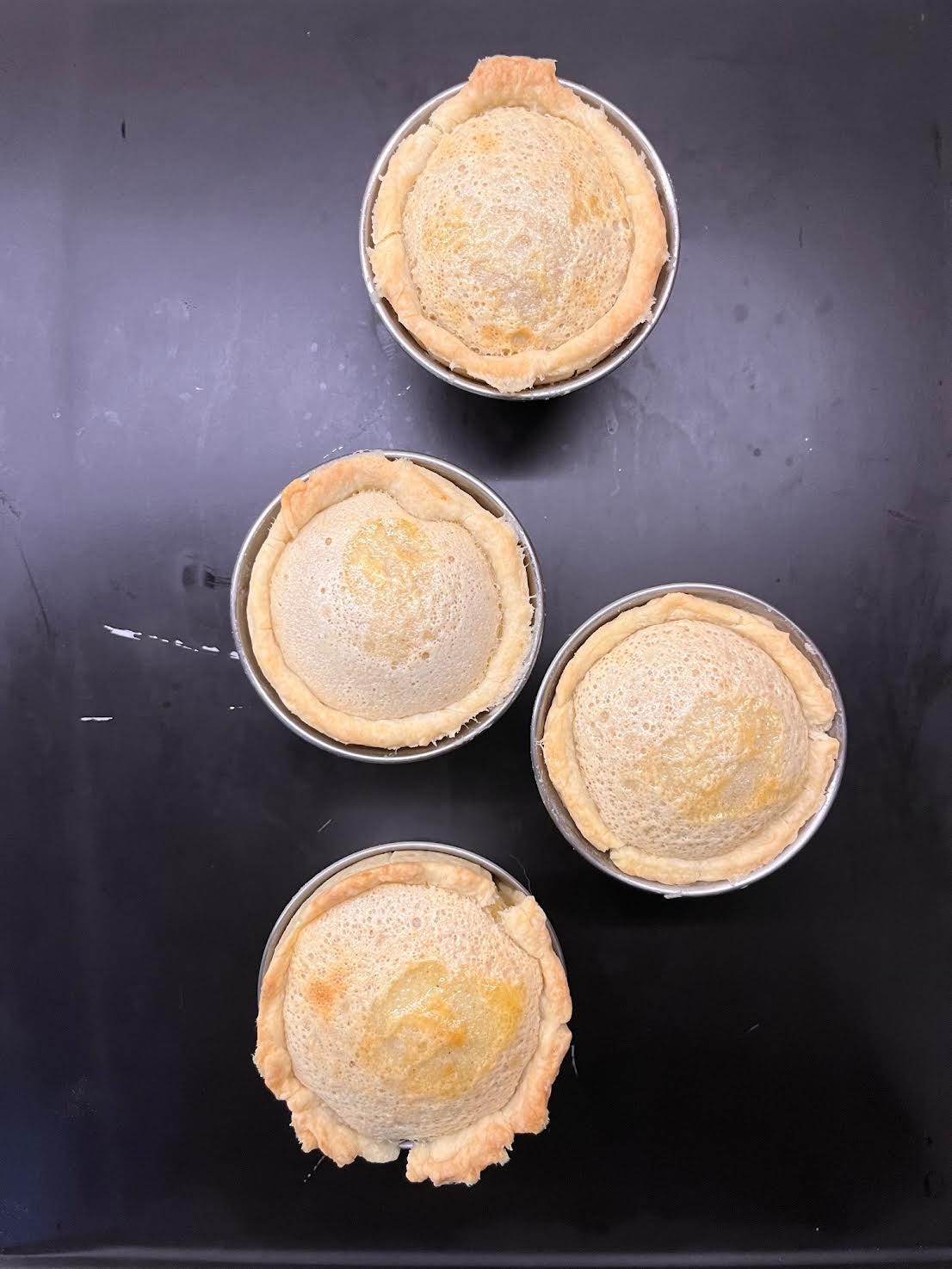

I just fell in love with the dariole. I made 2 versions, one with flour and the addition of cinnamon and orange flower water, the other with finely ground almonds and a pinch of saffron, both traditional, both a nod to the original pastry of the Middle Ages. Almost like a flan in the the filling sets densely, but it is somehow lighter. Perfect cradled in the thin pastry crust. As Carême wrote: “A true dariole shouldn’t have much of an effect when baked: it should only rise half a centimetre or a centimetre at most above the crust, forming an artichoke. This effect alone distinguishes good makers. These darioles make an excellent home dessert.” The surface doesn’t need to color too much, either. You’ll know they are done when the pastry is slightly browned and the filling is puffed slightly and will feel set and firm when lightly pressed in the center. Eat warm.

Darioles

Preheat the oven 350°F (180°C).

Butter 4 stainless dariole molds or a 6-cup muffin tin (I use silicone). I did cut out small circles of parchment to fit into the bottom of the buttered dariole molds.

Pastry crust

This recipe will line 4 dariole molds 2 ¼-inch high x 3-inch width at top or 6 regular muffin cups.

1 cup (140 grams) flour

2 teaspoons sugar

¼ teaspoon salt

5 ½ tablespoons (3 ounces / 85 grams) chilled unsalted butter

4 tablespoons cold water

Flour for rolling the dough

Place the flour, sugar, and salt together in a mixing bowl and toss to combine. Add the butter in chunks, tossing lightly in the flour so they don’t clump together. Using only your thumbs and the tips of your fingers, rub the flour and butter together until all the flour is moistened with butter and there are only tiny dots of butter left. Add the cold water and, using a fork, stir vigorously until a dough starts to form and all the dry ingredients are blended into the dough. Scrape the dough out onto a floured work surface and knead very quickly until the dough is smooth and homogenous.

Divide the dough into 4 or 6 pieces, depending on the baking recipients you’ll be using.

Roll out each piece on a floured work surface until thin. Carefully lift a round of thin dough and place carefully down into the dariole or muffin mold. Very carefully, press - without tearing - the dough into the bottom and “corners" of the mold then press into the sides. Press the thickness of dough that will form as the round of dough creates pleats up the sides, press up until the sides of the dough are thin, trimming off the excess of dough over the rim of the each mold. Repeat until the 4 dariole molds or 6 muffin cups are lined.

Cream Darioles

2 eggs

5 tablespoons (60 grams) sugar

3 tablespoons (35 grams) flour

½ teaspoon cinnamon

⅔ cup (150 ml) heavy cream

¼ teaspoon orange flower water

Small amount of butter to top darioles

In a medium bowl or - as I do - a large measuring cup with a spout - whisk the 2 eggs until blended. Whisk in the sugar and continue whisking for a couple of minutes until blended and thickening.

Stir the cinnamon into the flour and whisk them into the eggs and sugar until well blended and smooth. Add the orange flower water to the cream and whisk the liquid into the egg mixture until blended.

Divide the batter between the lined molds, filling about ¾ or a bit more. Place a small dot of butter on the top of each dariole.

Place in the preheated oven and bake for 30 to 40 minutes depending on the size and shape of the molds you bake them in and your oven. The surface doesn’t need to color too much, either. You’ll know they are done when the pastry is slightly browned and the filling is puffed and will feel set and firm when lightly pressed in the center.

Remove from the oven and remove from the molds as soon as they are cool enough to handle. Eat warm.

Almond Darioles

2 eggs

⅓ cup (70 grams) sugar

1 cup (80 grams) finely ground almonds

Large pinch saffron powder

1 cup (250 ml) milk, cream, or half milk + half cream

Same procedure as above, whisk the eggs and sugar together until starting to thicken, just a minute or two. Whisk in the ground almonds, in 4 or 5 additions, making sure each addition is smooth and there are no more lumps. Whisk in the powdered saffron then whisk in the milk + cream.

Fill the lined molds and bake for 35 - 40 minutes depending on the size and shape of the molds you bake them in and your oven. The surface doesn’t need to color too much, either. You’ll know they are done when the pastry is slightly browned and the filling is puffed and will feel set and firm when lightly pressed in the center. Mine formed what Carême referred to as “artichokes”…

The center of these darioles are creamy when eaten warm and firm up as they cool.

Thank you for reading and subscribing to Life’s a Feast by Jamie Schler. Please leave a comment, like and share the post…these are all simple ways you can support my writing and help build this very cool community. Let me know you are here and what you think. You are so very appreciated.

These remind me of 1980s famed Marks and Spencer custard tarts though they were lightly sprinkled with nutmeg on the top

What a delight! Culinary history is such a wellspring of insight to the true nature of life both in and outside the castle walls. You carry me back to my hours spent upstairs at Shakespeare & Co. (quai de La tournelle) in the 70s, pouring over, then drinking up all I could