Dionysus: Have you e'er felt a sudden lust for soup? Heracles: Soup! Zeus-a-mercy, yes, ten thousand times. ― Aristophanes, The Frogs

The French love peas and always have. Zeus-a-mercy, yes!

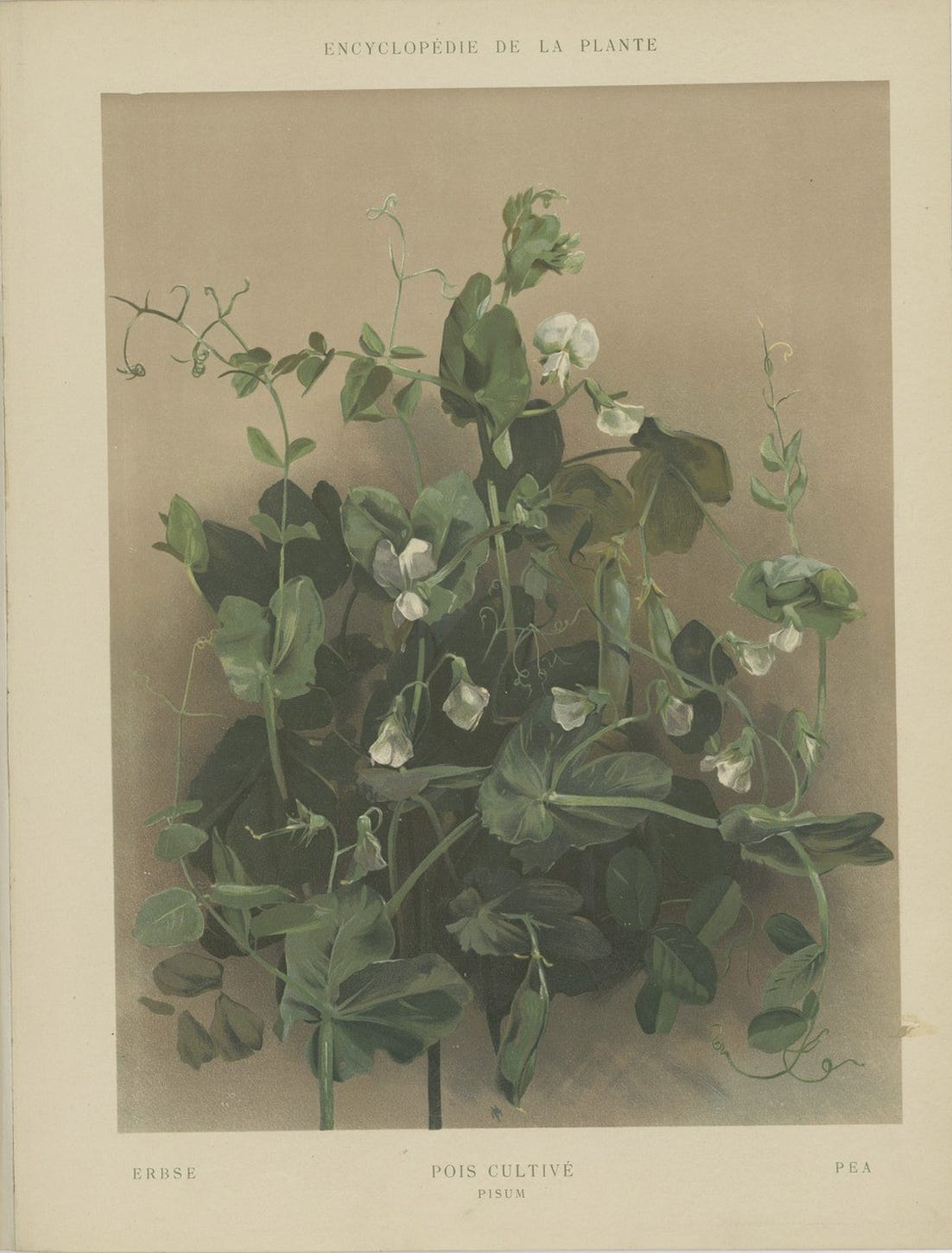

For centuries, peas were most likely not the cultivated sorts we know today, especially the tiny, tender green pea. But there were quite a number of varieties available and they were apparently quite esteemed. The earliest known cookbook in Europe, Marcus Gavius Apicius’ collection of recipes De Re Coquinaria or About Cooking, collected by the wealthy roman, chef, and fin gourmet in the 1st century, and first published in 10 volumes in the 4th, has quite a number of recipes using both fresh and dried peas. Peas are the main ingredient, the star, in a number of recipes, and in others, peas are part of a larger preparation, usually a fish, fowl, or meat dish. He has an entire chapter on De pisis; Pisa/Pisam or Conchiclam/Conchicla (peas in the pod) were cooked in broth or wine, blended and flavored with loads of fresh herbs, coriander, oregano, lovage, dill, fennel, cumin, and dried fennel or pepper, sometimes ginger and honey, lots of oil, and occasionally, of course, lard. And paired with an incredible variety of meats, fish, and fowl.

It’s obviously difficult to pinpoint when peas arrived in what is now France, but by the Middle Ages, when we have access to a good number of cookbooks, we know that peas were quite popular. Actually, even more than popular, they were a necessary and useful ingredient in medieval, and then Renaissance cooking. When Guillaume Tirel, better known as Taillevent, master chef to kings Charles V and Charles VI, jotted down his recipes around the the year 1300, to be published after his death as Le Viandier, he didn’t indicate whether the peas he used were fresh or dried. But we do see certain recipes for pois and others specifically for pois nouveaux or new peas. This could mean that the former are dried and the latter fresh, or it could refer to different varieties. But the peas, not new, are uniquely used in purée form; pea purée is used to make and thicken sauces and used as something to cook meat or fish in, sometimes, it appears, in the place of another liquid such as broth. He has a wonderful recipe cooking meat in pea purée with bread soaked in wine, ginger, cinnamon, saffron and other spices, verjuice and acidic wine to finish it off with that beloved medieval kick.

While we glance at the evolution of peas in general, the discussion is vast and fascinating, too vast to cover all in one post. So today I want to focus on dried peas (pois secs), better known and sold today as split peas (pois cassés), really a category unto itself in French cuisine. Drying peas was a form of conservation since the earliest days, a way to preserve the popular fresh pea to be eaten when fresh peas were not available. Split peas would come much later, but peas, and probably a number of varieties in green, white, and red, were dried, both on the plant and after harvesting. And both, as we just saw, are culinary staples in Europe and in France.

We start to be able to record and observe the popularity and culinary use of dried peas in the Middle Ages. We see a vast number of recipes for pois nouveaux, new peas, probably fresh peas, although we aren’t certain which variety this refers to, although we are sure that they cooked with shelled peas, or peas or beans removed from the pod, as well as peas contained in a pod that can be eaten, like the snow pea. We discover a number of ways of preparing this vegetable, and particular dishes that are found across many cookbooks by many different chefs, indicating that by the middle ages, people knew the best ways to prepare this legume. We do know “pois” or “peas” came in green, white, and red, and that fava or broad beans, chickpeas, and lentils were known and eaten in early Europe.

We begin to understand that dried peas, a practical process to preserve a fresh, seasonal vegetable, must have been a widely used, an inexpensive, efficient, and undoubtedly popular food. We know that dried peas are almost uniquely used to prepare soups and purées. We see this from cookbooks across the centuries. Le Ménagier de Paris, written and published around 1393 by Albertano da Brescia, has recipes for poiz nouveaulx, new peas, most likely fresh, as well as recipes specifically calling for poiz vielz, or old peas, which we can only assume are dried, “old” because they are allowed to age on the plant before picking, thus giving them the time to dry. Both Le Ménagier and Du Fait de Cuisine from Maître Chiquart, a cookbook dating from 1420, contain recipes for or instructions to use both purées and potages (soups) using peas; rarely calling for new or fresh peas: Da Brescia calls for pois vielz or old peas for his soup, Chiquart uses “white peas” for his purées (according to Heuzé, who we’ll meet in a bit, common dried peas were often referred to as “white peas”, losing their vibrant colors as they age). Pea purée was used quite often to cook meat in in the place of broth or another liquid, the pea purée sometimes thinned with white wine, or to thicken sauces and soups. That both of these authors, as well as Taillevent, call for new peas in many recipes, one can maybe jump to the conclusion that simply peas in an ingredient list could mean dried, as dried peas can’t really be eaten in the same way as fresh and require soaking, deep cooking, and puréeing.

“While peas can be allowed to dry on the plant before harvest, they can be dried once picked. Select tender grains and place them, freshly shelled, in a pot of boiling water. Once boiled, put them in cold water; then air-dry them on a white tablecloth for two or three days, turning them over from time to time. Change the tablecloth and expose them to the sun for five or six days. Then put them in a lukewarm oven, laid out evenly on racks, covered with paper, until they are completely dry. Finish by storing them in paper bags in a dry environment….so that rats cannot damage them, they keep much longer.” - L’École du Jardin Potager, Tome 1, 1822

While we guess about the peas in these early cookbooks, we can be pretty certain that Apicius himself cooked with dried peas. His recipe for Tisana taricha or Aliter tisanam, a gruel or porridge, is made by soaking and crushing a combination of chickpeas, lentils and peas; once the peas are cooked and soft, they are mixed with “plenty of oil, green herbs, leeks, coriander, dill, fennel, beets, mallows, cabbage strunks, all soft and green and finely cut, and put in a pot.” He then adds “fennel seed, origany, sylphium and lovage,” he adds broth to taste, and pours this over the porridge, "sprinkling some finely chopped cabbage stems on top.” His recipe for Pisam Adulteram - old peas - is a “tempting dish of peas cooked with brains, small birds or boned thrushes, chicken livers and giblets, thrown in a pan with broth, leeks, green coriander, pepper and lovage.” Da Brescia boils and drains his “old peas” twice before preparing his soup. But in what water? A tricky question in the year 1393 “because peas don't usually cook well with well water, and in some places they cook with fountain and river water, as in Paris, and in other places they don't cook with fountain water, as in Beziers.”

In 1558, Léonart Fuschs writes “We find in our country two species of peas: one grows along the ground, the other is a climbing plant, in French pois ramiers (snow peas). Peas are similar to fava beans (or broad beans) and we eat them “en entremets” (side dish or between courses) but they are different in two ways: they don’t swell or plump up like favas and they pass and descend more slowly through the belly than beans.” (L’Histoire des Plantes)

Jacques Dalechamps wrote Histoire Générale des Plantes in 1615 and discusses how age-old peas are, commonly eaten in ancient Greece when peas, shelled and split, were made into soup. And like Fuschs , he also speaks of two sorts of peas, those whose plants lie on the ground and those which climb. According to Dalechamps, the “pois nouveaux” or new fresh peas are eaten with their pod, so most likely snow peas. “Even the rich cook them with salted meat or lard, and make a strong, good meal out of them, which even dares to compare with the great banquets.” Much loved, indeed, and by all classes of society.

By 1705, Louis Lémery speaks of 3 types of peas in his Traité des Aliments or Treatise on Foods: the first that are “almost round, a color green at the start and become on drying angular, white, or yellowish. These peas are enclosed in long, cylindrical pods made up of two husks. The second are large, angular, a variety of colors, white and red, they are formed in large succulent pods. The last are white, small, and enclosed in small pods. The first two sorts are found in fields, and the second is cultivated in our gardens.” This is the first we read of peas being cultivated. But more of that in a future post….

And our old friend Lémery never fails to let us know of both the goodness and the dangers of each food one eats, and he doesn’t fail us where peas are concerned “Peas soften the acridity of the chest, soothe coughs, nourish a lot, are an emollient and a little laxative, mainly through their first boiling. Peas are windy (cause flatulence), and bad for those prone to kidney stones. They are suitable at all times, especially for young people, and for almost all temperaments, provided they are used moderately. However, people with coarse dispositions don't do well with peas.” Peas, Lémery states, are a popular food, and the smaller and greener they are, the better they taste. Peas are dried, he explains, in order to preserve them for a long time, but once dried, he warns, “they no longer have that same wonderful taste.”

Gustave Heuzé, French agronomist and Honorary General Inspector of Agriculture, also wrote of dried peas in Tome 1 of his fascinating book Les Plantes Alimentaires, Edible (Food) Plants, in 1873. “Dried peas are widely used in the countryside, and although they have their disadvantages, they are to be preferred in every respect to beans, because they are more digestible and less flatulent. These disadvantages disappear almost completely when the peas are stripped of their exterior shells; they are sold in food shops under the name split peas, and are used to prepare excellent purées.”

Joseph Favre complains about dried peas and beans in the Dictionnaire Universel de Cuisine et d'Hygiène Alimentaire in 1890 - or, more likely, those who don’t prepare them correctly “these (dried) vegetables are rarely sufficiently cooked; regardless of their age, they are left to soak for an insufficient time beforehand; then, the fat or old butter used gives them a rancid taste to which it's hard to become accustomed.” His entry for pois cassés - split peas - is separate and distinct from the entry for pois - peas, determining it to be a unique foodstuff: “dried peas are ground, shelled and halved. Two types are prepared: yellow and green. Split or dried peas,” Favre stresses, “are a real asset to home kitchens, hotels, boarding houses and hospitals.” Easy, efficient, nutritious, and cheap.

François Pierre de la Varenne is definitely using dried peas in soups in 1654. His recipe in Le Vray Cuisinier François for potage de purée de pois communs - listed in the index as pois vieux or old peas - has one cooking them in water until “fait” or done, possibly meaning soft. He serves this soup “green” by adding parsley, watercress, chervil, and capers. He serves the soup with fried bread. His recipe for pois passez, probably pea purée, instructs one to soak the peas, then drain them, and finally to cook them in hot water. This would only be done with dried peas. The cooked peas are then drained and puréed. The purée is cooked with butter, salt, and an onion stuck with cloves.

2 centuries later, dried peas are still being used and used in the same ways as back in medieval times (and the way they are still cooked today). Urbain Dubois explains in his 1876 book École des Cuisinières “lentils, white beans, yellow peas, and split peas are often used to make soups, primarily in winter. These purées,” he continues, “are easy to make and inexpensive: they give very good results if they are carefully prepared.”

Which brings us to the split pea soup. It was a common soup, a soup that could be made and enjoyed by the rich and poor alike, since the earliest days, even as the flavorings changed with the times. But it was Count Saint-Germain, War Minister under Louis XVI, that gave this soup the cultural oomph it needed to lift it up to a classic and an icon. The Count was crazy about peas. Crazy. A soup was created for him using fresh peas, but as fresh peas could not be had year round, he was contented with the same using dried or split peas. With a bit of lard or bacon, of course, a match made in heaven, or at least as far back as the middle ages.

There are two ways to prepare this luscious soup, with and without lard, bacon, or smoked pork. While the 1936 classic, L’Art Culinaire Moderne adds “a bit of ham” to its Potage Saint-Germain along with the onion and carrot that have been sautéed in butter and a “handful of leek greens,” not everyone does. Henri-Paul Pellaprat, a curious individual, chef and co-founder of Le Cordon Bleu cooking school in Paris, was an instructor at heart and wrote a vast array of cookbooks, for professionals, for homemakers or home cooks, and as tomes to collect and preserve the classics of traditional French cuisine, and it’s interesting to see his own variations of the same soup. His 1937 recipe in Cuisine Végétarienne for Potage Saint-Germain obviously contains neither pork nor chicken or meat broth, only split peas cooked in water to which one adds, once the peas are cooked, an onion and carrot cut into strips and cooked in butter along with the greens of a leek; once cooked completely, the mixture is puréed fine then thinned with vegetable broth. The soup is served garnished with peas, either fresh or canned. Pellaprat’s recipe in his 1950 L’Art Culinaire Français, now called Potage aux Pois Cassés dit Saint-Germain is the simplest of recipes. Split peas are cooked in water to which is added a chopped onion and chopped carrot; once cooked it is puréed then thinned with either water or broth, keeping the soup creamy but not too thick, and a pinch of sugar is added to “offset the bitterness of the split peas.” This soup is served either with butter-fried croutons or thickened with rice. 5 years later, his Potage aux pois Cassés dit St Germain in La Cuisine Familiale et Pratique has no lard or bacon, even as it’s a hearty family dish, only split peas, an onion, a carrot which are cooked together in lightly salted water then puréed, again with that pinch of sugar; this version is also served with either butter-fried croutons or thickened with rice.

Prosper Montagné’s 1938 and original Larousse Gastronomique has two recipes, separating the Potage purée de pois frais dit Saint-Germain and the Potage purée de pois cassés; the Saint-Germain is simply fresh green peas cooked in water then drained and puréed, the purée thinned with a light consommé then finished with a bit of butter and served with 2 spoonfuls of fresh and freshly cooked peas and chopped chervil. Very elegant and befitting a Count. The split pea soup is heartier, the pre-soaked then cooked dried peas are joined by a mirepoix of chopped lard, carrot, and onion sautéed in butter and seasoned with a bouquet garni and a handful of leek greens. Once cooked, the solids are strained out and the soup puréed. The purée is thinned with a light consommé and finished with butter and chopped chervil. This soup is served with fried croutons. The author notes that this soup can be made without the lard and thinned with milk in the place of the broth for a meatless version.

My own version is a blend of them all. I wanted to make the best tasting split pea soup possible using the simplest of ingredients; I decided not to use lard, bacon, or pork so the dish could be enjoyed by everyone. Adding a swirl of tangy crème fraîche to serve gave it just the flavor kick it needed to finish the dish perfectly. It really is so delicious, and such a perfect, warming, creamy yet robust soup for winter.

Potage de Pois Cassés

Split pea soup

The split peas must soak overnight, so plan accordingly.

10.5 ounces (300 grams) split peas, green or yellow

1 yellow onion

1 leek

1 carrot

2 tablespoons (30 grams) or a bit more butter

Salt and freshly ground black pepper

About 5 cups (1200 ml) chicken or vegetable broth; have more on hand in case you like a thinner soup

Chervil, fresh, for a few tablespoons chopped

Cubed bread for croutons

Butter to fry the bread for croutons

Crème fraîche - fresh cream, sour cream, or Greek yogurt for serving

Put the split peas in a large bowl and cover generously with cold water. Leave overnight.

The following day, pour the split peas into a large mesh strainer to drain. Run the split peas under cold water until the water runs clear (a good minute or two). Set aside.

Trim and chop the onion. Set aside.

Trim, peel and coarsely chop or chunk the carrots; trim, peel off the outer layer (discard), and rinse the leek really well to make sure there is no dirt or sand in the layers of green. Cut the leek in two lengthwise down the center then chop or thinly slice the leek. You can put the prepped carrot and leek together in a bowl and set aside.

Heat a couple tablespoons butter in a large Dutch over, sauteuse, or heavy pan. When it’s melted and sizzling, add the onion and cook, stirring, for a few minutes until soft, translucent, and just beginning to shrink. Add the carrots and leek and continue to cook, stirring constantly, until the onions and leeks are very soft.

Add the drained split peas, salt and pepper generously, and stir everything in the pot together well.

Add the chicken or vegetable broth, stir, bring to the boil, lower the heat to a simmer, cover the pot and cook for an hour. Check and stir the soup occasionally and add a bit more broth if you like (or wait until after puréeing).

Chop a couple of tablespoons of the chervil.

Melt another tablespoon of butter in a skillet or frying pan. When the butter is melted and sizzling, toss in the cubes of bread and fry, stirring and tossing often, until the bread is golden and crispy. Remove from the heat.

To finish the soup, at the end of the hour of cooking, add a tablespoon of the chopped chervil to the pot and, using an immersion blender, purée the soup well until smooth. Stir in another tablespoon of the chopped chervil. Add more broth if you like a thinner soup and reheat through.

Serve the soup hot in bowls, grind on a little more black pepper, and top with fried croutons and a spoon of crème fraîche.

Thank you for reading and subscribing to Life’s a Feast by Jamie Schler. Please leave a comment, like and share the post…these are all simple ways you can support my writing and help build this very cool community. Let me know you are here and what you think. You are so very appreciated.

I like how dried peas are "split" in English and "broken" in French. It makes one take pause and consider what hardships these poor peas must have gone through to arrive at their current condition.

Also, it's my understanding that peas were a crucial first crop for farmers in the Middle Ages, since they are fairly quick to grow and helped bridge the hunger gap that typically happened in the early spring when winter food stuffs had run out so, um, "Yay, peas."

Peas, peas, they bring me to my knees. A little more wine please!