Plums and prunes hydrate, soften, refresh, quench, and stimulate the appetite. ... Prunes quench and soften the bitterness and bile. - Le Médecin des Dames, où l’Art de Les Conserver en Santé (Women’s Medicine, or the Art of Keeping Them Healthy) by Jean Goulin, 1771

Le Cannameliste Français written by Joseph Gilliers in 1771 defines pruneaux as “plums that one dries in an oven at a moderate temperature or in the sun.” He goes on to explain “We make compotes with them for Lent, we cook them by throwing them into boiling water…we drain them and turn them into compote (stewed prunes); we put them into Burgundy wine, or into water, according to the taste of those to be served, with sugar and a little cinnamon, and we allow them to cook slowly.”

Prunes - plums dried in in an oven or in the sun - found their way to France in the 12th or 13th century, carried across the miles by knights returning from the Middle East, along with spices and exotic fruits and vegetables. And they - prunes, not knights - immediately found their way into French cuisine, joining the other fruits - figs, raisins, apricots, dates - that were dried for preservation, eaten as they were, at both the beginning and the end of meals, or used in cooking, quite popular in both savory and sweet dishes, but primarily savory.

Medieval cuisine was particularly spicy, ginger, cinnamon, saffron, and pepper, as well as cloves and nutmeg, finding their way into most dishes (as well as set out in bowls on the dinner table for each guest to add as they pleased) not, as many suspect, in order to cover the taste of bad meat, but because it was the culinary taste of the time. Spices were also served and consumed for their health benefits, quite a fashionable trend in the Middle Ages. Food was not only rich in spices, but there was a preference for tart and acidic flavors, as well, and a particular penchant for sweet-and-sour or savory-sweet. Many dishes blended an acid in the form of verjuice, vinegar, or wine, while honey offered the sweet component, of course, with the copious addition of fresh or dried fruits, not only in meat and poultry dishes, tourtes, and rissoles, but fish (carp, eel, tuna), as well.

Spiced wine was also in vogue during the Middle Ages through the Renaissance, again not only for the culinary appreciation, but these libations were considered to have important health benefits. One of the most popular drinks of the time was hypocras, spiced wine, often served and drunk heated, much like today’s mulled wine. “Le boute-hors (vin et épices) termine le repas…” Meals, according to Le Ménagier de Paris, a guidebook written in 1393 by a young bourgeois gentleman on a woman's proper behavior in marriage and running a household, were finished with wine and spices. Bochet, a medieval mead, was a popular drink of fermented honey infused with spices. Claret or claré was an alcoholic drink made from honey cooked with wine.

Pears poached in hypocras, like today’s pears poached in red wine and spices, was quite a popular dessert in the Middle Ages; apples were cooked in wine along with dried fruits and spices as a filling for tarts. I imagine it wasn’t uncommon to find dried fruits, prunes included, poached in wine, as well. Hypocras was often the base of a sauce, according to Taillevant’s influential Le Viandier; a “bouillon” or “potage” - broth or soup - was made by cooking beef shank with hypocras, cinnamon, ginger, cloves, pepper, and grains of paradise, a bit of sugar to taste, finally tossing in a bit of vinegar to keep the liquid from boiling. This concoction was served with roasted peacock, pheasant, partridge, cranes, and skylark.

And from the beginning, when prunes were introduced into French cuisine, they often seemed to go hand-in-hand with wine. Dried confit plums (prunes), dates, raisins, and figs, along with pine nuts are added to numerous savory dishes in Maitre Amiczo Chiquart’s 1420 Du Fait de Cuisine (Kitchen Facts), often chopped and “très bien lavées en vin blanc” (very well washed in white wine). Libro de arte coquinaria, an Italian cookbook written around 1450 or so by Martino di Rossi (or di Rubeis), includes a recipe for a sauce aux pruneaux secs in which the prunes are first soaked in wine then ground or puréed with almonds and bread, then cooked with a little verjuice and wine, to which is then added "a little sapa (vin cuit or sweet cooked wine) or sugar”, balancing the acidity and the sweetness.

Cookbooks from the medieval and renaissance periods are difficult to come by, but we do know that prunes were an integral part of French cooking.

And then we lose track of prunes completely, other than a brief mention in François Pierre de la Varenne’s Le Cuisinier François written in 1654 where, for the first time I could discover, prunes were treated on their own rather than as a flavor component, a sweet balance to the acid, in a savory dish or sauce. La Varenne includes a very simple recipe for prunes cooked in water and sugar until the liquid reduces to a syrup.

In the 18th century, prunes cooked in wine suddenly appear again, yet, oddly enough, in medical books aimed at children, adults, the poor, or those serving in the military or at sea, as well as books and pamphlets treating specific illnesses, from fevers to constipation. An extremely bizarre book, Introduction au Traité de la Conformité des Merveilles Anciennes avec les Modernes (Introduction to the treatise on the conformity of ancient wonders with the modern) written in 1572 by Henri Estienne indicates that prunes, like many foods and spices, are already being thought of in medicinal and medical terms, albeit with a curiously extreme religious influence: Estienne seems to make his dietary recommendations by blending religiosity (the ancient wonders) and bodily health (modern medicine): “Prunes are also necessary to make a dinner complete: yet it is necessary to have some. By these prunes, which are black and of good substance, I mean abstinence from sin, mortification of the flesh, and bodily godliness.”

In 1700, Claude de Pinteville published Le Petit Trésor de Santé. Contenant plusieurs remèdes à beaucoup de sortes de maladies (The Little Treasury of Health. Containing several remedies to many kinds of diseases), a collection of extracts from the books and memoirs of his father, M. Pinteville. M. Pinteville recommended one “often eat prunes cooked in water and honey at the start of meals and as an appetizer between courses” if suffering from kidney pain. To combat a continuing fever, one must “drink an infusion made from prunes, honey, and sorrel root.” In 1728, Pierre Fauchard wrote Le Chirurgien Dentiste, ou Traité des Dents (Dental Surgeon, or Treatise on Teeth) in which he gives several formulas and concoctions for removing grime or stains from as well as whitening the teeth, which he refers to as “liqueur pour les dents” including one preparing marshmallow (Althea) root boiled with and infused in red wine, adding prunes, honey and sugar, creating a syrup in which the root is candied, making it more agreeable. Jean Goulin, cited at the beginning of this post, also recommends crazy concoctions for the cleaning and whitening of women’s teeth, including soaking marshmallow root in a stew of black prunes, alum, honey and sugar; the prunes can be substituted for red wine.

And in 1738, Nicolas Alexandre published the Dictionnaire Botanique et Pharmaceutique in which he instructed making a laxative syrup by cooking prunes in white wine with sugar and senna until the liquid is a syrup.

The prune is now recognized as one of the best medicines for constipation, a laxative that “releases the stomach”. But, finally, a century later, it is starting to be understood that one can benefit from the health qualities of this dried fruit while enjoying it as a dessert at the same time. In 1871, Dr. Collongues, the resident doctor in the thermal spa town of Vichy, wrote Notice sur les quantités d'eau minérale qu'il convient de boire pendant et après la saison de Vichy : leur meilleur mode d'administration et le régime alimentaire à suivre chez soi après le traitement thermal (Instructions on the amounts of mineral water to drink during and after the Vichy season: their best mode of administration and the diet to follow at home after the thermal treatment) in which he recommends pruneaux laxatifs du dessert. He begins his preparation by infusing 10 grams of cassia or senna follicles in boiling water before straining. 16 prunes are then added to the infusion with a glass of Bordeaux wine, a bit of cinnamon, sugar, and 2 slices lemon, the concoction boiled until the liquid is reduced to a syrup. Just “2 or 3 of these laxatives prunes…gives the best results for constipated people” and, he concludes, they are “good dessert prunes.”

And it only took a few centuries for the prune to find its way into the dessert chapter of French cookbooks.

The first recipe for a good, boozy compote de pruneaux or stewed prunes (compote de pruneaux sounds so much sexier, doesn’t it?) I could find in a cookbook was in Louis Bailleux’s Le Pâtissier Moderne of 1856. He favours using the famous prunes from the towns of either Agen or Tours; the prunes are placed in a container filled with boiling water, covered and sealed, and allowed to soften for 4 hours. The prunes are then drained and placed in a pot large enough that the prunes fill the pot halfway. The pot is then filled ⅔ full with a good wine, just enough sugar is added to sweeten lightly. The zest of one lemon is bundled and tied and tossed into the pot with the prunes, and the contents brought to the boil. The prunes are allowed to gently finish cooking in the oven for 2 hours. The peel is removed from the pot before the prunes are served. In a pretty compotier or footed fruit bowl, of course.

Our old friend Urbain Dubois, never behind the times, includes an interesting recipe for compote de pruneaux secs in his 1888 La Nouvelle Cuisine Bourgeoise. He softens and plumps prunes in boiling water before draining; he then mixes the prunes with wine, either red or white, a zest, most likely lemon but I’d love to think that he offers the choice between lemon or orange zest, and just a pinch of sugar. The stewed prunes are then lifted out and placed in a terrine, the liquid is cooked down with more sugar. Dubois explains that cooking the prunes themselves with too much sugar will wrinkle the plumped prunes.

In 1913, Le Journal des confiseurs, pâtissiers, glaciers, fabricants de chocolats, biscuits, fruits confits, confitures, conserves, etc, a publication for professional pastry chefs, chocolate makers, etc, has a very modern recipe for stewed prunes under the heading “The Art of Using Prunes” : prunes are cooked in white wine with a pinch of sugar until plumped. After the prunes simmer in the sweetened wine for half an hour, they are removed from the liquid which is then left to reduce until a syrup. The prunes in the wine syrup are served in a compotier, that fancy footed fruit bowl. Another professional publication, Fruit à Noyaux (Stone Fruits), published by The Fruit Preservation Industries in 1925, recommends conserving or storing prunes in a good quality red wine, making “an excellent preparation.”

Then we see the elevation of stewed prunes to something a bit more special, more dessert-like, more deserving than their oft-maligned status.

In 1934, Bertrand Guégan offers us a beautiful pruneaux à la crème in Le Cuisinier Français in which prunes are soaked for 24 hours in a half liter of good red Porto; once the prunes are plumped, a half liter of a light red Bordeaux is added, along with a vanilla bean and a cup of sugar; this is then cooked.… The pot with the Porto and Bordeaux syrup and the boozy prunes is then put aside for 3 days for maximum maceration, the prunes soaking up the wine with the hint of vanilla. The prunes and syrup are served, most elegantly, in a crystal bowl drizzled with a liter of thick fresh cream accompanied by slices of brioche mousseline. Prunes served with cream, while being sophisticated enough for elegant tables, are also being prepared in more modest kitchens. Pruneaux à la crème fouettée (prunes with whipped cream) makes its appearance in the 1932 La Cuisine Familiale, pour manger mieux et dépenser moins (The Family Kitchen, to eat better and spend less) in which the prunes are poached simply in water with sugar and (yes! finally!) the zest of an orange; the prunes are then puréed. Heavy cream is whipped and sweetened, placed in a dessert bowl and “crowned with the prune purée.”

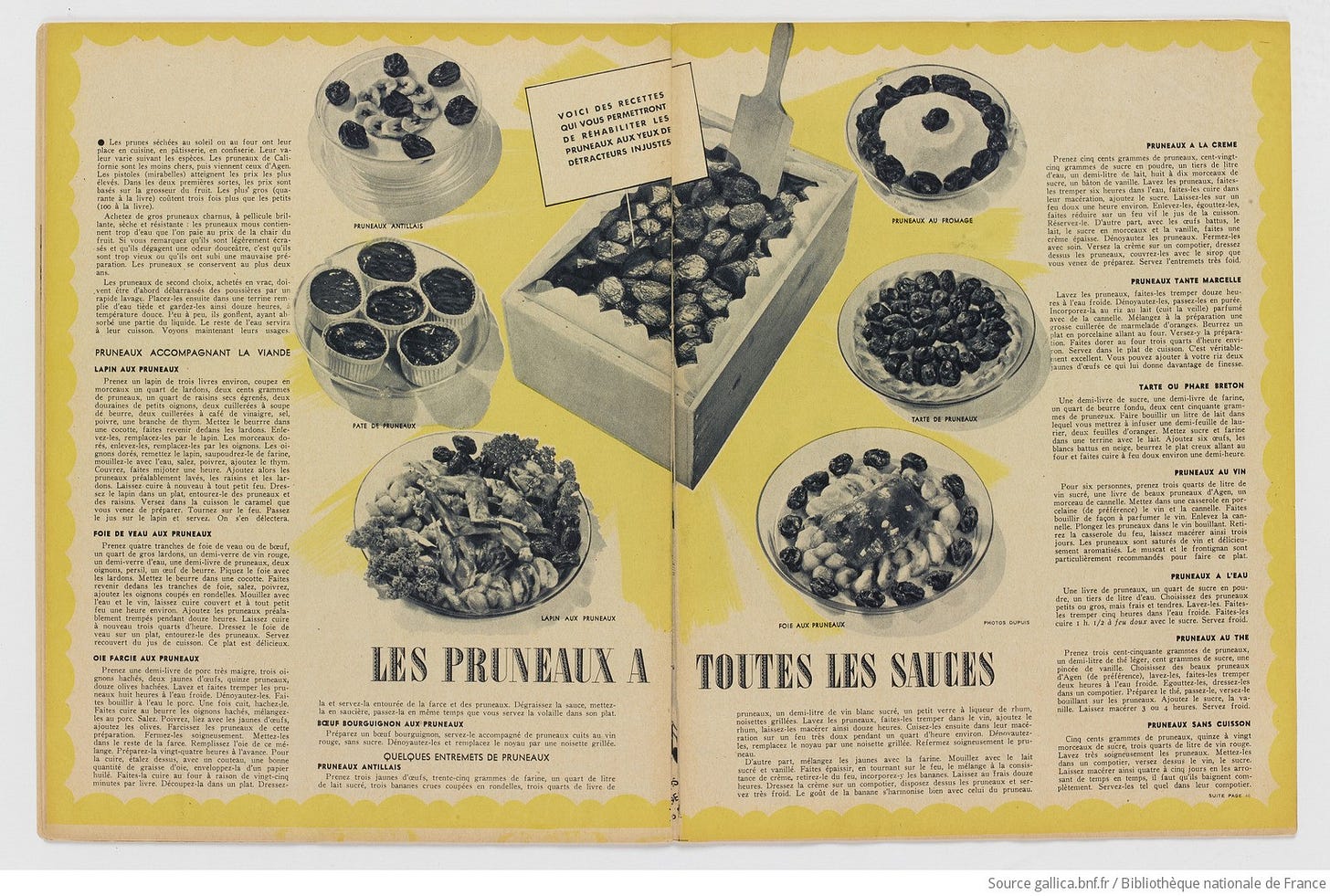

The February 4, 1938 issue of Marie-Claire magazine has a double-page spread dedicated to the prune, stating squarely in the center of the 2 pages “here are the recipes you need to rehabilitate prunes in the eyes of unfair detractors” followed by a dozen savory and sweet recipes using prunes, including pruneaux au vin (prunes cooked in cinnamon-infused Muscat until “saturated with wine and deliciously aromatic”) and pruneaux à la crème (prunes cooked in sweetened water perfumed with vanilla and served with a pastry cream and the cooking liquid reduced to a syrup).

Laurence Berluchon, a gastronomic writer and columnist best known for her writings on the gardens of Touraine, penned an in-depth article on the Prunes of Tours for the October 1,1949 issue of La France à Table (magazine of gastronomie et tourisme) featuring the region of Touraine (where I currently live). She recounts “We’re invited to taste the “prunes with cream” and we’ll say “Now that’s good!” with an accent of verity and enthusiasm to which disgraced palates cannot aspire and which would not deceive Brillat-Savarin.” She continues, leading into a recipe, “Our chef assures us this is a 100 year old recipe: soak 36 fine/large prunes in half a liter of red port for 14 hours. Once plumped, cook them in the Porto with as much old Bourgueil or Chinon (framboisé), half a vanilla bean, and 200 grams sugar. Let them cool in the liquid for 3 days; it’s important as they will become soft and flavorful. To serve, arrange them in a crystal goblet and drizzle them with fine cream and serve with slices of brioche mousseline. It’s simply exquisite.” (Exquisite indeed: one notices this is the same recipe Guégin offered in his cookbook, changing out the Bordeaux, of course, for a local old Bourgueil or a fruity (framboisé) Chinon red.)

Compote de pruneaux - prunes poached in red wine and spices - stewed prunes. Don't let the word prunes fool you. Today I’m sharing with you a gorgeous recipe, crazy in its simplicity, yet sensual and intriguing in texture and flavor. Wine-poached prunes, a very adult twist on the stewed prunes and dried apricots that my father made, that I grew up on and loved, a very modern rendition on a very ancient French dish.

Moist pitted prunes (call them dried plums if you will), are poached in a fruity red dessert wine and water with a touch of cinnamon and orange until tender and infused with the heady mix of wine and spices. I’ve made this with what is possibly the only red dessert wine in the world, Giovanni Allegrini Recioto della Valpolicella Classico, but you could use any full-bodied fruity red wine or port wine. Glistening, slippery wine-poached prunes that burst on the tongue make a sensational dessert served simply with whipped cream or over vanilla ice cream, or serve the prunes spooned over a simple pound cake - a quatre-quarts. Drizzle with the luxurious syrup that results from simmering the cooking liquid down and you have an incredibly adult pleasure.

The wine-poached prunes, in the best French medieval fashion, are equally at home served as a condiment or sauce with any roasted meat or fowl.

Wine-poached prunes with orange and cinnamon

This recipe appears in my cookbook Orange Appeal, Gibbs Smith Publishing, 2017.

10 ½ ounces (300 grams) moist pitted prunes (weighed without pits, about 45 to 50 prunes

¼ cup (50 grams) granulated white sugar

⅛ teaspoon cinnamon

½ inch (1 cm) thick orange slice with peel

2 cups (500 ml) total liquid - ¼ cup (65 ml) red wine + ½ cup (125 ml) orange juice + 1 ¼ cups (310 ml) cold water -or- replace ¼ up (65 ml) of the water with more wine

* note: you can add half a vanilla bean to the poaching liquid, if you like.

Place the prunes, sugar, cinnamon, orange slice, and the liquid (and the half vanilla bean, if using) in a saucepan, bring to a boil, lower the heat and simmer for 10 - 15 minutes until the prunes are plump and tender but have not exploded. Using a slotted spoon, carefully remove the prunes from the liquid to a bowl and continue to simmer the liquid with the orange slice (and vanilla bean) until reduced by about a half, another 12 - 15 minutes. The liquid will thicken as it cools. Remove and discard the orange slice (and the vanilla bean).

Serve the prunes warm in individual bowls with some of the syrup and, if you like, topped with whipped cream or ice cream.

If making the poached prunes ahead of time, they can be served at room temperature or gently reheated with the syrup just until warmed through.

Thank you for subscribing to Life’s a Feast by Jamie Schler where I share my recipes, mostly French traditional recipes, with their amusing origins, history, and anecdotes. I’m so glad that you’re here. You can support my work by sharing the link to my Substack with your friends, family, and your social media followers. If you would like to see my other book projects in the making, read my other essays, and participate in the discussions, please upgrade to a paid subscription.

Jamie, here's a funny story. When our kids were in their early teens, someone gave us a decent-size container of homemade fudge sauce. My wife and I liked to scrape out a spoonful after dinner. To prevent our kids from finding our stash, I labeled the container Prune Compote. It was effective for quite a while, until one decided to see exactly what "prune compote" was. We still make references to it 30 years later.

I suddenly got hungry for the leathery dried prunes in my fridge while reading this engaging account of the elegant pruneaux au vin of France and their rich and delicious history. It really is a far cry from the stewed prunes my dad ate so religiously every morning (for medicinal reasons!). I can only imagine how delicious they would be with ice cream, whipped cream or even pound cake! Thank for another excellent piece, Jamie!