Love chocolate thoroughly, without complexes or false shame, because remember: 'without a grain of madness, there is no reasonable man’. - François de La Rochefoucauld (1613 - 1680)

While chocolate had been known for thousands of years in large parts of the world, it only arrived in France in 1615 with the marriage of Anne of Austria, daughter of Phillipe III of Spain, with Louis XIII. Anne arrived at the court with her personal contingent of maids and servants in tow, among which were those that knew well how to prepare her chocolate in the Spanish style, at that time seen as a curiosity and an eccentricity in France although quite a common habit in Spain. After the death of Louis XIII some 30 years later, it is said that she - now the regent to her son, Louis XIV - began to impose her habit of drinking chocolate upon the court and among the clergy.

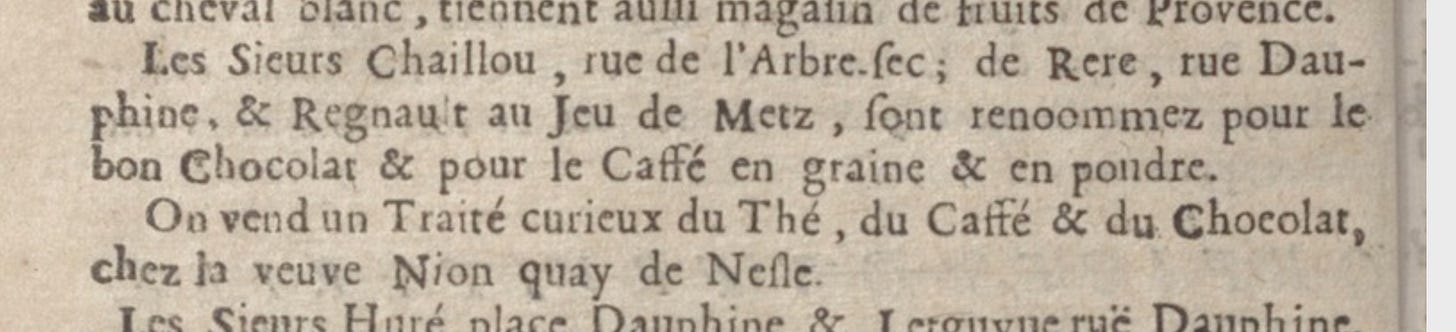

Cardinal de Mazarin, France’s chief minister and official lover of Anne, so crazy about chocolate himself that he had his own personal chocolate maker in his service, conferred the title Chocolatier du Roi on David Chaillou on May 28, 1659 in the name of Louis XIV, granting him the exclusive right to manufacture and sell chocolate throughout the kingdom for a period of 29 years, making Chaillou France’s first official chocolatier. Chaillou opened France's first chocolate shop in Paris at the corner of la rue de l’Arbre-Sec and la rue Saint-Honoré facing les Halles. He used the chocolate paste made from cocoa not only to prepare the drink but in cakes and cookies, making him a pioneer in the French chocolate industry.

But it wasn’t Anne who made the taste for chocolate popular in France, creating a veritable craze, but Maria Theresa, daughter of Philip IV and another Infanta of Spain like Anne, who also brought the tradition of chocolate with her from her home country when she married Louis XIV in 1660. At the Court of Louis XIV, Maria Theresa had the reputation of “having only two passions: the King and chocolate.” And while the court’s enthusiasm for this “drink of many virtues” increased, her husband the king wasn’t convinced; he considered it “un aliment qui trompe la faim mais ne remplit pas l’estomac” - “a food that fools hunger but doesn’t fill the stomach” - and looked down upon his queen’s habit.

Chocolate, at this time, was a luxury, a highly valued commodity reserved for the royal court and the upper classes for its taste as much as for its sophistication. And its extravagant price. But chocolate was also highly prized for its health benefits and was used in health regimes, medical treatments, and in the preparation of medicines. For a long period of time, chocolate was thought by some to be an aphrodisiac leading many religious leaders to forbid its consumption, but the reputation of its curative powers was so strong among the French that it soon became commonly used in pharmaceutics and by doctors. Chocolate was thought to aid in digestion and strengthen the spleen, fight against both mental (depression) and physical fatigue, and strengthen intellectual performance, stimulate fertility, and cure colds and coughs.

Possibly the first mention of chocolate in French was in the translation of "Dialogos muy apazibles escritos en lengua española y traduzidos en frances” (Extremely pleasant dialogues, written in the Spanish language and translated into French, with French annotations where necessary to explain the few difficulties of the language, all of which is very useful to those who wish to hear said language) by César Oudin in 1608. There is one brief mention, an annotation under a dialogue in which someone mentions the word “caco” - “Caco or otherwise Cacao is a certain fruit, resembling an (?? this word is indecipherable) and held in great esteem in America and serves as money for the Indians and is used to make a very dark, very delicious brew that they call chocolate.”

In 1631, Antoine Colmenero de Ledesma, Spanish doctor and surgeon, wrote Du chocolate : discours curieux divisé en quatre parties, translated from the Spanish into French by René Moreau, professor of medicine in Paris, who added notes where needed. This 59 page pamphlet was a discourse on the benefits of chocolate, inspired by and dedicated to Monseigneur l’Eminentissime Cardinal de Lyon to “satisfy his curiosity after hearing some people rebuff the use of chocolate, people who evidently did not understand the virtues of this foreign drug”. Colmenero explains “The number who drink chocolate today is so large… in the Indian countries, Spain, Italy, Flanders, but particularly in the Royal Court of Spain… yet there are people who are in doubt of the advantages and the damage it causes.” The author decided to write this pamphlet to explain to the public the preparation of chocolate and the variety of ingredients that goes into its making and the difference between good chocolate and bad, so that each person could select the best for his own infirmities.

A few years later, in 1637, Pierre d'Avity, French historian and geographer, penned Le Monde, ou La description générale de ses quatre parties. Avec tous ses empires, royaumes, estats et républiques (The World, or the general description of its four parts. With all its empires, kingdoms, estates and republics). He just touches on cocoa: “The principal use of this cocoa consists in brewing what they call chocolate which they strongly promote in this country (America), even as it induces nausea or queasiness to those not used to it as it has a foam on top that is extremely disagreeable. The Spanish, who are already used to drink it, are extremely fond of chocolate. They drink it hot, cold, and warm, and they even make a paste for the stomach and against catarrh (bad head and lung colds).”

But the battle between whether chocolate was a food or a medicine raged. The upper classes and royalty enjoying this delicious drink several times a day for pleasure in place of coffee might have used the excuse put forth by doctors, pharmacists, and apothecaries of chocolate’s multitude of health benefits to be able to consume more cups each day, but the religious community, in a conundrum of what exactly chocolate was, debated the question fervently. Was chocolate a food, a drink, or a medicine? In fact, the debate had been going on in ecclesiastical circles for a hundred years; from the moment cocoa arrived in Europe and was turned into a beverage, the religious community religiously (ha!) debated whether it was considered food or drink, or in other words, whether or not one could drink it during Lent or whether it would break fast.

In the 16th century, many people, especially women, commonly sipped chocolate, even during religious services, as a restorative to better endure the long ceremonies. In 1569, and contrary to other voices in the Christian church, Pope Pius V, stating “this delicious drink brings serenity to the soul,’’ decided that chocolate, since it was made with water, did not break the fast. Others in the Church specified, though, that drinking chocolate during fast days was fine, but it did “reduce the merits of the Christian who consumed it,” especially if the reasons for drinking it were to defy the religion, drinking it simply for pleasure. In 1624, a Viennese theologian Joan Fran Rauch penned a treatise condemning the consumption of chocolate in convents and monasteries, blaming “this violent inflamer of passions” on a spate of pregnancies among the nuns in several Austrian convents and the disintegration of morals amongst the monks. Rauch railed against chocolate as an aphrodisiac, that it “heated both minds and passions” and he exhorted the religious community to absolutely refrain from drinking it in order to avoid further scandal. His treatise was translated into several languages, and Rauch went so far as to request Pope Urban VII to “excommunicate the infernal drink”. But the monks evidently pushed back - hard - and supposedly had as many copies of the pamphlet destroyed as they could.

Finally, in 1662, Cardinal Francesco Maria Brancaccio, an important figure in the Catholic Church, defended the consumption of chocolate, declaring it “in conformity with the canons of the Church,” adding “it would be a pity to leave the privilege to the Devil”. He also, once and for all, decided chocolate’s fate: “That it nourishes cannot be denied, but it does not follow that it is a food… no more than wine, beer, or other usual beverages that the Church permits during the hours of abstinence.” The Cardinal thus declared that chocolate was allowed during the fast days of Lent to everyone’s delight.

Possibly the first dissertation written about chocolate in France was the Traitez nouveaux & curieux du café, du thé et du chocolate: ouvrage également nécessaire aux médecins & à tous ceux qui aiment leur santé (New & Curious Treatise on Coffee, Tea, and Chocolate: a work equally necessary for doctors & for all who love their health) published in 1671 by Philippe Sylvestre Dufour, a French apothecary and druggist, banker, and author based in Lyon.

After his chapters on coffee and tea, Dufour explains that “the use of chocolate has become so common in Europe, principally in Spain, then in England, in France, then in Italy, that we can no longer consider it as a beverage particular to America where it was born, but as a drink naturally among us. This obliges me to examine its composition and benefits, as I did for coffee and tea, to truly know if it deserves all the praise that we confer on it.”

Cocoa, Dufour explains, as well as the flavoring ingredients added to cocoa to make chocolate, were each considered drugs on their own, or at least all used in health regimes or pharmaceutical treatments and preparations, and he strongly advised that each must be prepared and added in the dose prescribed in order to have the desired medicinal effect. The flavoring ingredients added to cocoa included cinnamon (fortifies the stomach, dissipates winds/gas, corrects bad odors of the mouth, calms stomach pains, and strengthens the heart), Mexican pepper - chili or pimiento (fortifies the stomach, takes away the negative effects of chocolate such as acne), cloves (fortifies the stomach), vanilla (fortifies the stomach and the heart, calms repulsive moods, effective remedy for venoms), and sometimes anise and achiote (calms crude, rude, and crass moods which cause difficulty in breathing and urine retention). The chocolate mix is then sweetened with sugar which, he explains, is not only added as a sweetener to balance out the natural bitterness of the cocoa, but, as with jams, “to preserve the chocolate as well as to keep out worms”.

Dufour included a chapter on the Préparation & mélange des drogues pour faire le chocolat & manières de la boire (the preparation and blending of the drugs to make chocolate and the manners in which to drink it). The chocolate is dissolved in a liqueur to create “an extremely delicious and very healthy beverage. Chocolate”, he writes, “nourishes and fattens, it calms and fortifies the stomach and heart, attenuates “thick and viscous humours” (depression, fatigue, bad or crass moods), calms fever and stops dysentery,” among other medicinal uses. “People who have exhausted and weakened stomachs from colic, diarrhea, the winds, copious evacuations, weakness of the stomach are perfectly well with the use of this drink.”

The Marquise de Sévigné’s instructions to her daughter in a series of letters - her famed correspondence is abundant and expansive - illustrates the continued questions around chocolate and its uses. In a letter dated February 11, 1671, the year Defour’s book was published, she writes “But you are not doing well; chocolate will set you up.” But on April 15 of the same year, she writes “Chocolate (…) flatters you for a while and then suddenly ignites a continuous fever that leads you to death.”

Le bon usage du thé, du caffé et du chocolat pour la préservation et pour la guérison des maladies (The proper use of tea, caffé and chocolate for the preservation (of health) and healing of diseases) written by M. de Blegny, medical advisor and “artist of the King, appointed by His Majesty to the research and verification of new medical discoveries” in 1687 includes an entire chapter on the use of chocolate as as part of a treatment to cure venereal disease (“the most universal of gallant diseases”) whereas chocolate is “given in the form of an opiate”. Doctors already understood that chocolate paste contained properties that were both stimulants and antidepressants, provoking euphoric and calming effects close to opium. Dr. de Blegny seems to cure patients over a period of weeks by alternating “anti-venereal” chocolate with wine (a Burgundy, a Spanish wine, muscat or a claret), herbal tea, baths, and the application of hot water bottles all over the body, evidently to make the patient sweat. He devotes a chapter to the preparation of the drink, the “most common and most agreeable way to take chocolate.”

Half a century after chocolate had been introduced to the French, it still remained a costly and artisanal product reserved for the upper and royal classes and the medical world. And it was still primarily taken in liquid form, heated with either water or milk, stirred until frothy, the foam a signature quality of the brew, and drunk. Chaillou, in his shop on rue de l’Arbre Sec began adding chocolate to some cakes and cookies, but apparently it took until the 1670s for chefs to begin creating other forms of desserts with this prized flavoring, and then only timidly.

Our old friend François Massialot might very well have been the first chef to include chocolate in the recipes of his cookbooks, and it’s easy to see how they evolved over time. He begins quite simply in the 1691 edition of Le Cuisinier roïal et bourgeois with a crème de chocolat (milk boiled with sugar, then the addition of egg yolk; chocolate is then added off the flame and stirred until melted, put back on the flame, finally strained then “served as you like”) and, curiously, a savory stew, macreuse en ragoût au chocolat, of beef, salt, pepper, bay, bouquet garni, livers, several varieties mushrooms, chestnuts, and with chocolate added along with the seasonings. In the 1698 edition, he added the chocolate version of a type of set almond cream like a blanc-manger.

Massialot’s 1698 edition of Nouvelle Instruction pour les confitures, les liqueurs, et les fruits has very few chocolate recipes, including only biscuits de chocolat (cookies made from egg whites, sugar, and only enough grated chocolate to give it “scent and color”), eau de chocolat (a water, chocolate, and sugar sorbet or ice), along with “the manner to prepare chocolate.” By his 1715 edition, he had added recipes for the preparation of milk chocolate along with traditional chocolate, conserve de chocolat (2 ounces of chocolate melted with a pound of sugar, the mixture then “dressed as one likes” - most likely used as one would any confiture or jam), crème de chocolat, massepain au chocolat (chocolate almond paste), pastille de chocolat (a candy), along with the biscuits de chocolat and the eau de chocolat glacée.

His 1740 edition didn’t go much further in chocolate innovation, but that’s another whole century….

Petits pots au chocolat

This simple dessert was one of the first desserts made with chocolate to find its way into French cookbooks, and it is still a classic, still just as simple, and still just as good. Cooked rather than baked, this delicate, creamy, full-flavored custard is versatile, both homey and elegant.

2 cups (500 ml) milk or half milk and half cream (I usually use half low-fat 2% milk + half heavy cream)

6 ½ ounces (200 grams) semi-sweet or bittersweet chocolate

6 egg yolks, beaten just until blended

¼ teaspoon ground cardamom, optional

½ teaspoon vanilla extract or ½ a vanilla bean, split, the seeds scraped out and reserved

You can also add up to 2 tablespoons of sugar, if you like, to be cooked with the milk/cream and chocolate, depending on your taste and choice of chocolate.

Prepare 6 small dessert glasses, verrines, or tea or demi-tasse cups.

Place the egg yolks in a large pyrex (heatproof) mixing bowl.

Grate or chop the chocolate and place in a small saucepan with the milk/cream; add the vanilla bean plus the scraped seeds, if using. Cooking over very low heat, scald the mixture (bring it just up to the boil), stirring to make sure the chocolate is completely melted and combined and does not burn.

Remove the scalded milk/chocolate mixture from the heat and gradually whisk into the egg yolks in a slow, steady stream while whisking constantly. Whisk until well blended. Stir in the ground cardamom and the vanilla extract if using.

Lift out the vanilla bean and discard. Pour the custard into the desserts glasses or cups. Cover with plastic wrap and chill until firm.

Serve with plenty of very lightly sweetened whipped cream.

Thank you for subscribing to Life’s a Feast by Jamie Schler where I share my recipes, mostly French traditional recipes, with their amusing origins and history. I’m so glad that you’re here. You can support my work by sharing the link to my Substack with your friends, family, and your social media followers. If you would like to see my other book projects in the making, read my other essays, and participate in the discussions, please upgrade to a paid subscription.

I would commit crimes to have your research skills. I know what I'm making after my, um, procedure next week.

Wonderful article, again. The history then sent me down the rabbit hole to see if Quai Nesle might be related to Nestlé (not at all) But I ended up the scandalous Tour de Nesle Affair. French history is as deliciously decadent as the cuisine.