“What delight to savor a vanilla meringue, still moist from a mistress's kiss!” - Les Bains de Paris ou Le Neptune des Dames by J.P.R. Cuisin and dedicated to the fairer sex, 1822

“Looking through the Old Testament and mythology for examples of vampires, one doesn’t find any. But it has been proven that the dead drank and ate, since so many ancient nations put food on their tombs. The difficulty was to know whether it was the soul or the body of the dead man who ate. It was decided that it was both. Delicate, insubstantial dishes like meringues, whipped cream, and soft fruits were for the soul, roast beef was for the body.”

Thus is our introduction to the fragile, ethereal meringue. Voltaire knew exactly what foods to accord to the soul and which to the body. His book Questions sur l’Encyclopédie (volume 9) of 1772 is an extremely odd place to begin our look back to the origins of the meringue, but rather apt, tying this delicate confection to the lightness of the soul.

Meringue is a concoction of whipped egg whites and sugar, often with a touch of lemon juice or zest to stabilize the whites as they are beaten thick, tall, and stiff. Or, as was described by François Massialot in 1692 in Nouvelle Instruction pour les Confitures, les Liqueurs et les Fruits, “It's a little confection of sugar, very pretty and very easy. It is also very convenient in a kitchen, as it can be done in a moment."

There are 3 types of meringue, French meringue (also called ordinary meringue), Swiss meringue, and Italian meringue. As meringue was defined in the 1926 Larousse Ménager, Dictionnaire Illustré de la Vie Domestique (Household Larousse, Illustrated Dictionary of Domestic Life overseen by Chancrin and Faideau): “A very light pastry made with egg whites and sugar, mixed in different ways depending on the purpose.” In other words, “Variations exist by changing the quantities and type of sugar, but above all the way it is incorporated into the mass.”

French or ordinary meringue is quite simply egg whites beaten with sugar until stiff, then piped or spooned out and baked.

Italian meringue is made by beating egg whites with cooked sugar. The final meringue itself is not cooked. This is the meringue you will find on lemon meringue pie, Baked Alaska (omelette norvégienne), and in the preparation of marshmallows.

Swiss meringue is made by whisking egg whites with sugar over simmering water in a bain-marie, the whisking then continued off the heat until the mixture is cooled and thickened. This is the most stable of the meringues. This is also the most versatile of the meringues, used baked or not, and most commonly used to make buttercream frostings.

“It was in 1720,” writes Prosper Montagné in the first edition of Larousse Gastronomique in 1938, “that, according to culinary historians, this small pastry was invented. This invention, if there was one, because it seems that well before this time egg whites were used in pastry, is attributed to a Swiss pastry chef named Gasparini who practiced his art in Mehrinyghen, a small town that some authors place in the state of Saxe-Cobourg-Gotha, while others place it in Switzerland.” Mehrinyghen, or Meiringen, is said to have given its name to the meringue, but this fact is often disputed, the origin of the word never settled upon.

Montagné was right about one thing: meringue was being made in France long before it was called meringue. The first appearance of “this small pastry” in a French cookbook was in Lancelot de Casteau’s Ouverture de Cuisine in 1604. He called them neige seiche (sèche) or dried snow - here you must understand that egg whites whipped and beaten until thick, firm, and white are called neige - blancs montés en neige (“whites whipped/increased to snow”) - neige the French word for snow; correctly done, the whites will definitely look like pure white, tall and billowy snowdrifts. De Casteau’s meringue is what is now known as an Italian meringue, the sugar melted then boiled with a bit of rose water “to perfection” before beating into the thickened whisked whites.

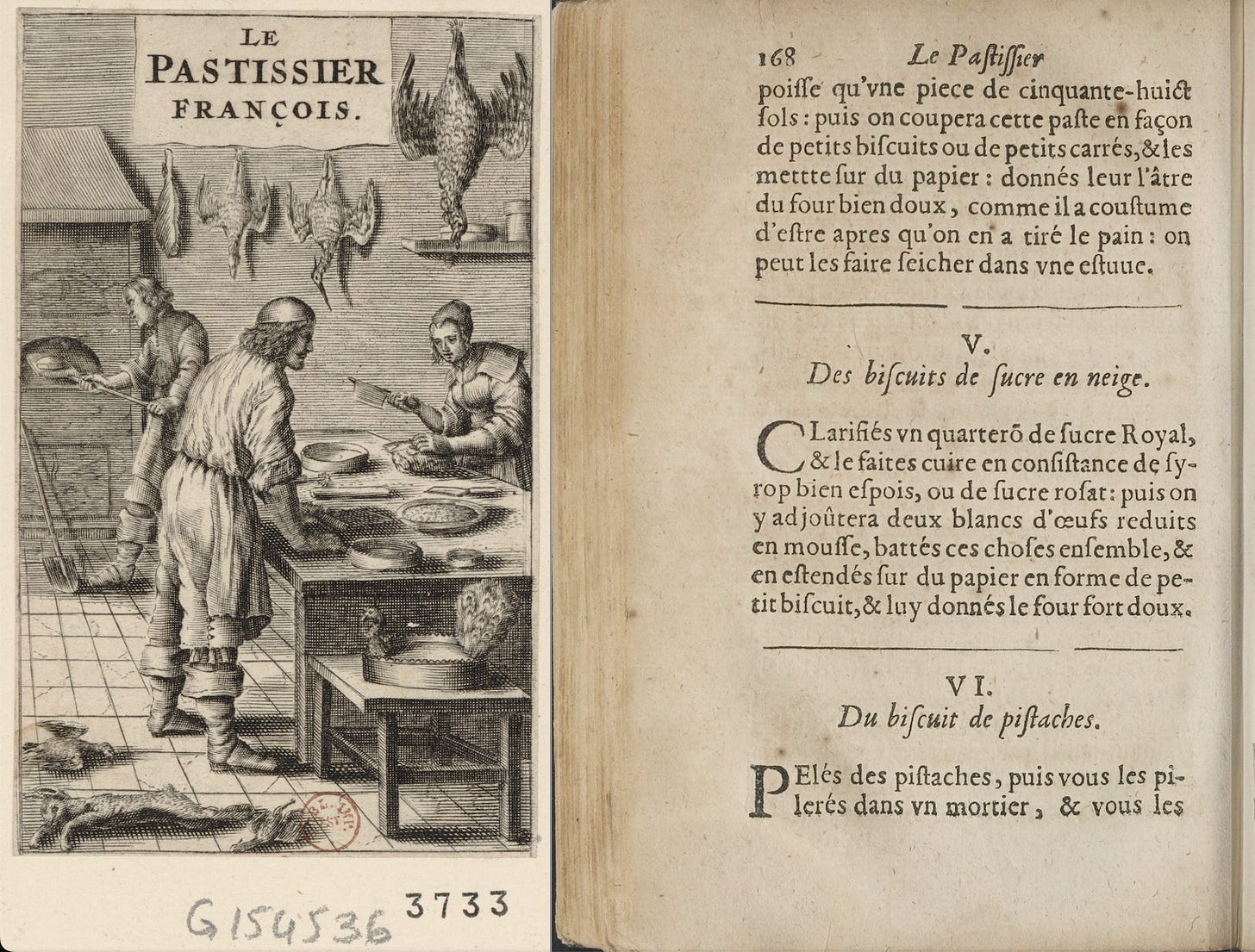

Meringues next appear in 1653 in François Pierre de la Varenne’s rare Le Pastissier François. His recipe for des biscuits de sucre en neige is a perfect Italian meringue - sugar cooked to a very thick syrup - added to egg whites that have been beaten until foamy, then beaten together, the mixture shaped into small biscuits or cookies on paper then baked in a very slow or moderate oven.

It is our old friend François Massialot who finally calls a meringue a meringue. The first appearance in a cookbook of this pastry referred to as a meringue is in his 1691 cookbook Le Cuisinier Roïal et Bourgeois. His meringues are proper French meringue, egg whites beaten until they form “la neige à rochers” or thick white peaks like snow on crags or rocks. He adds lime zest, the acid helping stabilize the firm whites, 3 or 4 spoonfuls of sugar, and then shapes into rounds or ovals the size of a walnut. He dusts them with a bit of fine sugar then bakes carefully. He places a small fruit, a tiny bit of raspberry, cherry, or strawberry, “depending on the season” into the hollow center then sandwiches the meringues two by two. He also offers a recipe for pistachio meringues. His meringues are made to garnish other desserts.

A year later, Massialot includes a small chapter in his second cookbook Nouvelle Instruction pour les Confitures, les Liqueurs et les Fruits on des meringues & macarons, including the same 2 recipes as his previous book but building on the concept of the meringue by adding finely ground almonds and making macarons, indeed a type of meringue.

In 1750, Joseph Menon divides his meringues into méringues liquides (with the accent over the e) and grosses meringues séches (without the accent) - liquid meringues and large dry meringues. The liquid meringues are simply the whites beaten with lime zest and sugar then dropped into rounds the size of chestnuts and baked. They are, like Massialot’s, sandwiched together with a bit of fruit. The large dry meringues become more like what we call a Pavlova today, one large meringue (thus the name) baked in the shape of a large round or mound and served topped with orange flower marmalade, red currant jelly, or apricot jam. Around this time, other cookbook authors are creating new recipes using meringue, starting with Joseph Menon’s 1749 La Science du Maître d’Hôtel Cuisinier with recipes for potage au lait meringué (a strange “soup” of milk cooked with eggs and sugar which is then poured into a pre-baked meringue-edged serving dish lined with slices of a delicate white bread and served), ris meringué (rice pudding topped with meringue which is then lightly colored in the oven), and rôties meringués (eggs scrambled in a reduced and thickened cream made of milk, lime zest, crushed almond macarons, and sugar placed atop grilled slices of bread and topped with meringue). Menon’s 1755 Les Soupers de la Cour (volume 4) has two recipes - crème meringuée and autre (another) crème meringuée that seem to be 2 versions of today’s lemon meringue pie but without the crust. He also creates another scrambled egg dish, sweetened and lemony, topped with meringue - oeufs meringués. His oeufs à la Dauphine are an interesting version of oeufs à la neige: a rich cream is made of cream, sugar, yolks and flavored with lemon and cinnamon, whites are beaten en neige, spoonfuls of these whipped whites are poached in the cream; the cream and the poached whites are placed in a platter and topped with more meringue. François Marin had a crème au caramel meringué à la glace in which large meringues are set atop chilled crème caramel in his Les Dons de Comus in 1758. Marin’s oeufs en meringue is a savory dish, something like what today we would think of as devilled eggs, the filling made with the hard boiled yolks and sorrel cooked in butter and seasoned; the “stuffed” hard boiled whites are then topped with a meringue for, he writes, “un effet meringue”, a meringue effect. Indeed. These authors also continue to include recipes for simple meringues made of ordinary or French meringue baked into small cookies.

“Never had we seen, never have we seen since so many tarts & so many meringues together, & never had she eaten so many.” - Le Cabinet des fées, ou Collection choisie des contes des fées, et autres contes merveilleux by Louise de Bossigny Auneuil, 1786

Dr. Jourdan Le Cointe’s cookbook for healthy eating, La cuisine de santé, ou Moyens faciles & économiques de préparer toutes nos productions alimentaires de la manière la plus délicate & la plus salutaire, d'après les nouvelles découvertes de la cuisine française & italienne (Healthy Cooking or easy & economical ways to prepare all our food products in the most delicate & healthy way, according to new discoveries in French & Italian cuisine - I just like this title) published in 1790 includes meringues in his list of Des Entremets en Pâtisserie Maigre or lean (light or possibly low-cal) pastry, referring to them as “highly sought after and found on the best-served tables”.

L. H. C. Macquart begged to disagree. In his 1798 Dictionnaire de la Conservation de l’Homme, his book on “hygiene and physical and moral education” claimed outright that “there are very few stomachs that do find themselves well with (meringues), the most delicate of delicacies”. A fact disputed in a review of his book in the January 1779 issue of Journal des Sciences, des Lettres, et des Arts. “Without a doubt, there must be many things of use in this dictionary, but there are certainly many useless things, as well…All doctors will not find themselves in agreement with the author. That's why we don't recommend relying too much on what he says about meringues.”

Madame la Comtesse de Genlis penned La Maison Rustique in 1810, “for the education of youth, or Return of an Emigrant Family to France” and opens chapter 5 with “In general, pastry is very unhealthy.” She goes on to divide pastries into 3 groups: those that are harmfully unhealthy (rich pastries such as brioche, pastries made with puff pastry, meat pies and pâtés), less unhealthy (massive, dry and crunchy pastries such as biscuits and flans), and very light pastries made without butter or fat which are not at all unhealthy or unwholesome. She includes meringues in this last category.

“Yes, you've eaten ten tarts, six meringues, & had two cups of ice cream à là crême, so it's no wonder you're sick.” - Adèle et Théodore, ou Lettres sur l’éducation by Madame la Comtesse de Genlis, 1782

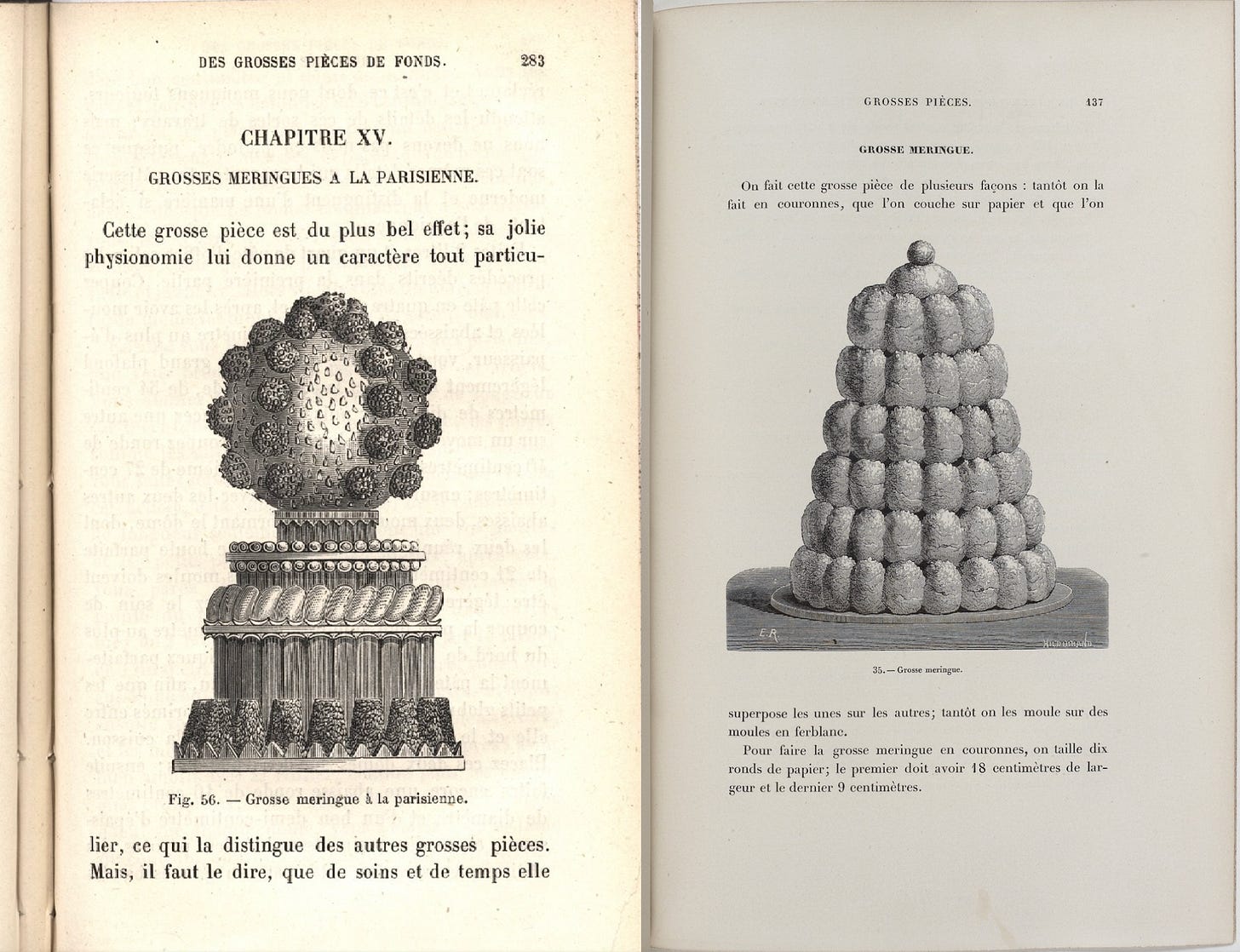

Carême, of course, takes meringue to a whole new level in the new century. His 1815 Le Pâtissier Royal Parisien reveals such creations as pommes méringuées en forme de hérisson (syrup-poached apples filled with apricot marmalade sitting atop apple marmalade masked in meringue in the form of a hedgehog), grosse méringue à la parisienne, and la méringue montée et au gros sucre, his enormous desserts using meringues baked in various shapes as both building blocks and decorative accents for these architectural centerpieces. As Comte Cousin de Courchamps writes in 1853 in his Dictionnaire Général de la Cuisine Française Ancienne et Moderne: “All that good taste and gastronomic experience, all that French savoir-vivre and gallantry could have inspired on this sweet entremets, could never have rivaled Mr. Carême's praises of meringue. “Meringue,” says M. Carême, ”is so loved that the entremets served with it are never tempting enough. There isn't a single gathering where every guest doesn't want to indulge in several. They are cherished like jewels by the ladies, are admired and savored by gourmands as a delightful tribute; the ladies easily eat two or three of these delicious cakes, as their composition is light and as meltingly smooth as the whipped cream which garnishes them, and that, by this reason, their delicate stomachs are never disturbed.”

Carême, the great Carême, created the necessary buzz around the sweet little meringue, showing how it could be used as both element and decor, equally simple and elaborate. And from then on, pastry chefs were off and running.

In 1856, Urbain Dubois and Émile Bernard began instructing readers how to create decorative accessories from baked meringue, using either French or Italian meringue. La Cuisine Classique includes directions for meringue mushrooms, meringue walnuts (“meringue can be used to produce an infinite number of imitations”), and small meringues piped into various tiny shapes using a paper cone, adding either finely grated chocolate, orange or lemon essence, or “any other flavor” to the meringue, varying both color and flavor. He also pipes out cannelons or sticks, adding grated chocolate, carmine (“for a lovely pink”), or vanilla for meringue decorations in 3 colors.

In 1865, Pierre Lacam offers recipes for coffee meringues, raspberry meringues, English meringues, Italian meringues, Russian meringues, and Swiss meringues, and tiny meringue cases in which a corkscrew of meringue tops candied cherries which is then sprinkled with chopped almonds in his innovative cookbook Le Nouveau Pâtissier-Glacier Français et Étranger. He uses meringue not only to encircle or top various desserts, but as a base for others, as well. Pierre Lacam, pastry chef and culinary historian, according to Joseph Favre in the Dictionnaire Universel de Cuisine Pratique, was the first to use Italian meringue as integral parts of entremets or pastries. Favre should know as he and Lacam were contemporaries.

By the end of the century, we see the creation of meringue desserts such as oeufs à la neige, Charlotte de pommes meringuée, fanchonnettes, flans of all sorts topped with meringue, and a slew of other pretty little pastries and petits fours - soupirs (sighs), viviennes, mars - in which meringue is used as a decorative topping (Manuel Pratique du Pâtissier-Confiseur-Décorateur by Émile Hérisse, 1894). And gringalets, rochers, carottes, and pommes d’api (Le Pâtissier Français by Bernard, 1895). Hérisse also introduces us to the term meringuage, the art of preparing a meringue. And by the turn of the century and into the new, meringue - Swiss, French, and Italian - is being used in more and more ways, to cover cooked fruits, riz au lait, cakes, tarts and tartlets, and soon ice cream bombes and other creations - des entremets meringués is now a category unto itself.

But the meringue wasn’t just an exciting, diverse tool for pastry chefs. The simplicity and diversity of the meringue quickly made it popular across classes and in all homes, easy to prepare by chef, cook, housekeeper, or housewife. “Meringue crusts can be made with various essences, flavored like fondant,” instructed the author of La Pâtisserie et le Dessert à la Maison in 1866 (Pastry and Dessert at Home written by une ménagère - a housewife herself). “Meringue,” she continued, “is used to decorate a large number of cakes - make a meringue paste - spread it on your cake to a thickness of a cent piece. - Make designs with the tip of a knife and bake at a very low heat. Meringues can be used instead of cookies in charlottes.”

By 1923 and Le Répertoire de la Cuisine by Théophile Gringoire and Louis Saulnier, meringue seemed to be so common that the authors felt no need to give specific instructions for preparing meringue other than “8 whites beaten until stiff (montés en neige). Mix with 500 grams vanilla sugar”. They then offer several recipes using meringue, especially meringue baked into little cups or baked, chopped, and folded in, adding crunch to creams, with such charming names like the colinette, baisers de vierge (virgin kisses), caprice, mousse Monte-Carlo, etc, as well as dozens of desserts, ice creams, and pastries covered in soft Italian meringue. The 1947 cookbook La Pâtisserie de Marie Claire by Jeanne Grillet contained recipes for desserts “destined for the family table” and included meringues, meringues au chocolat, meringues à l’italienne, meringues ordinaires, meringues suisses, meringuettes, and meringuage pour fonds (meringues used as bases, like a dacquoise, much like a pie crust would).

Meringues are divided into two hemispheres, in the middle of which one puts whipped cream. It is the most sought-after of treats; there are few stomachs that don't benefit from meringues. - Médicine, Encyclopédie Méthodique, 1816

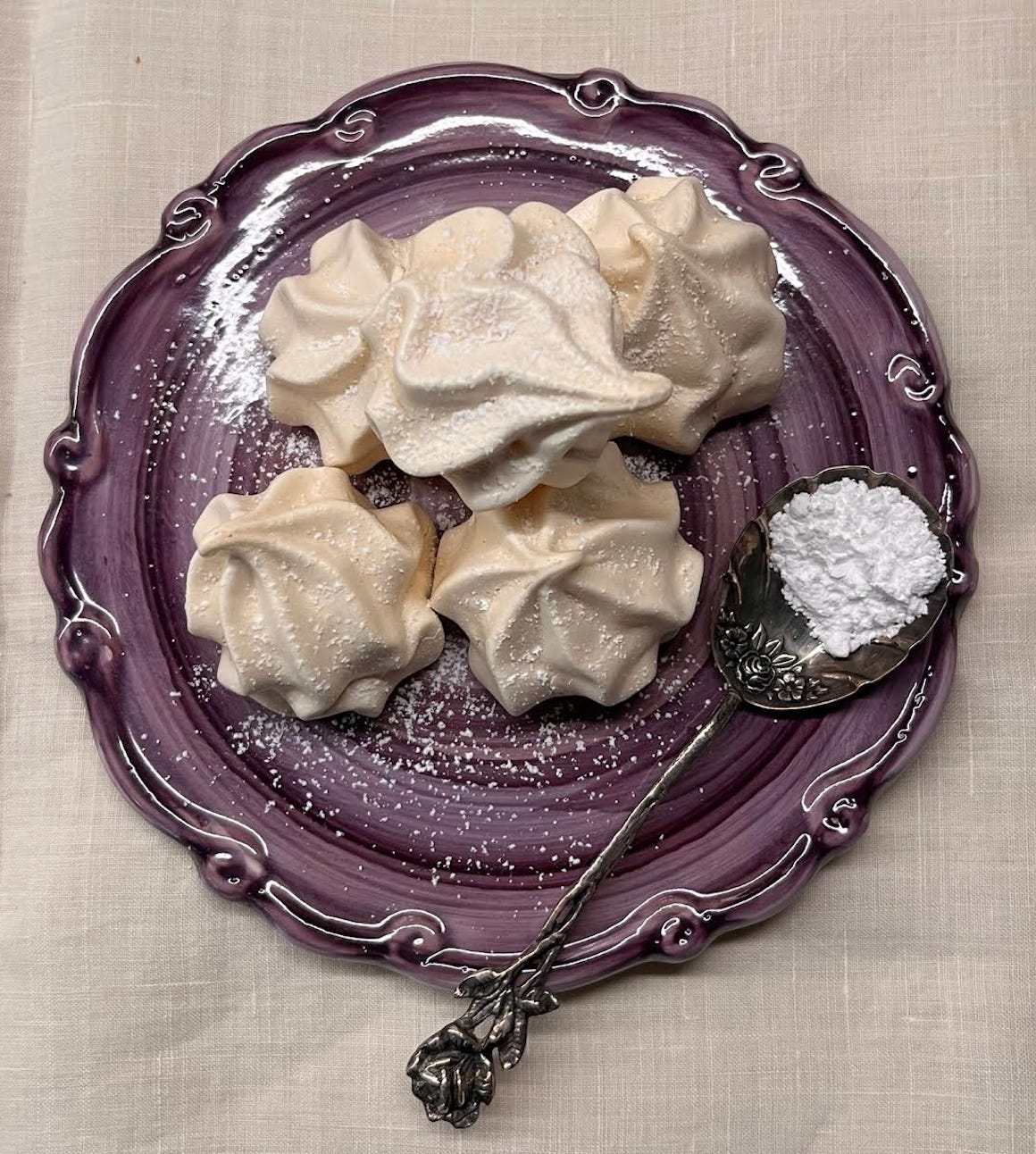

But let’s get to my topic here today; as we’ve seen, there are a few types of meringues used for and in a multitude of dessert and pastry creations. The meringue I want to talk about here is the cookie, that simple cookie made simply with an ordinary French meringue just like François Massialot’s back in 1691. The very first meringue in France is still wildly popular and commonly found in bakeries today.

The baked meringue has a hard, crunchy outer shell and a tender, moist, often chewy interior. It is thought that the first meringues in France were served to King Stanislas in Nancy. It was he, no doubt, who gave the recipe to his daughter Marie Leczinska, the wife of Louis XV, who also grew to love them. Like the madeleine and soupe à l'oignon, also introduced to Marie by her father Stanislas, this assured the popularity of the meringue, turning the upper crust of the Court and Paris onto these pretty little pastries. Marie-Antoinette was also apparently very fond of meringues and it is said that she made them with her own delicate and royal hands in her private abode Le Trianon, no doubt dressed as a milkmaid. She supposedly used her handmade meringues to prepare vacherins, as well.

Meringue, while simply 2 basic ingredients and so simple to make, will only succeed if careful attention is paid to the rules for beating egg whites. And I couldn’t have stated it better than in the October 5, 1927 issue of L'Express de l'Est et des Vosges:

“Everyone knows that meringue is made from egg whites and sugar....While meringue is very simple to make, two essential conditions must be met: the whipped egg whites must be absolutely firm, and the cooking process must be slow and well-regulated.” The author follows with excellent and minute instruction: the bowl (copper, of course) must be cleaned, rubbed with lemon just before using, then dried with a clean cloth. The whisk must have fine (thin) wire loops, not too many and not too close together and must be extremely clean, used only for the meringue. It is recommended to rub the tines or loops with lemon juice then begin by whisking moderately (in small bursts) then, once the whites begin to foam, accelerate the whisking movement until you are whisking vigorously as the whites begin to cling to the whisk loops. This is when you begin adding the sugar. These instructions are still de rigueur and are extremely important to follow.”

In other words, both the bowl and the whisk/beaters must be perfectly clean and grease and moisture free. The whites must be spotless, not even the tiniest speck of yolk or shell should have fallen in - it is advised to separate the eggs one at a time into a separate cup or bowl, then adding each to the mixing bowl when confirmed perfectly clean.

Eggs are easier to separate when chilled but need to be at room temperature when beaten for maximum volume and thickness; separate the eggs cold, storing the yolks in an airtight container and returning to the refrigerator (use them in the next day or two), and leave the whites out to come to room temperature for at least 20 minutes. Add a few drops of lemon juice to the separated whites which will help stabilize the beaten whites.

For smooth meringues, I highly recommend using a combination of superfine sugar and powdered/confectioners sugar; regular granulated sugar won’t completely “dissolve” leaving tiny grains in the meringue. Regular granulated sugar will require longer beating which is okay but not recommended.

While a copper pot is ideal for beating egg whites, I use plastic for excellent results. A glass bowl in not recommended; as my pastry chef at Ferrandi where I was an interpreter told the class, glass doesn’t allow the whites anything to “grip” onto so, as they are being beaten, will slip and slide on the glass surface, ultimately leaving a very fine layer of liquid white on the bottom. Copper or plastic allows the whites to “grip” thus creating perfect neige.

When piping the meringue onto the baking sheet, push it slowly and gently from the pastry bag, guiding the size, height, and thickness of each meringue; you should carefully detach the meringue from the batter coming out of the tip, not allowing it to break but rather lifting the pastry bag up and creating an elegant point.

Meringues must bake at a very low heat so it isn’t even necessary to preheat the oven a long time before putting the meringues into bake. The meringues will bake at 200°F (100°C) for about one hour, then just turn the oven off and allow the meringues to cool in the oven as the oven cools, for anywhere from one hour to overnight.

Vanilla and Coffee Meringues (meringue kisses)

You will need a pastry bag with a fairly wide tip - of your choice - or just drop mounds of the whites onto the baking sheet. You will also need a baking sheet. I recommend you read the tips above the photo before starting.

4 egg whites (they should weigh 4.2 ounces or 120 grams total)

Few drops lemon juice

½ cup (100 grams) superfine granulated sugar

1 cup (100 grams) powdered or confectioners sugar (*see note)

1 teaspoon vanilla extract

1 - 2 teaspoons coffee extract, if desired

* lightly spoon the confectioners sugar into the measuring cup until slightly mounded, then level with a flat blade. Once you have measured out a cup of the sugar, sift the powdered sugar into a bowl to break up any lumps and lighten it.

Preheat the oven to 200°F (100°C). Prepare your pastry bag and tip - I used the wide star tip - and set it into a tall drinking glass.

Add just about 3 drops of lemon juice to the egg whites either when they are separated or just before beginning to beat. Make sure the whites are at room temperature before beginning.

In a medium or medium-large mixing bowl (preferable not glass), begin beating the egg whites on low speed for 30 seconds then increase speed just slightly to medium-low. When the whites are frothy, add 2 tablespoons of the superfine sugar. Continue beating until the whites turn opaque and traces are left in them from the beaters (very soft peaks should form if you life the beaters up) then add another tablespoon of the sugar. Once the sugar is beaten in, gradually increase the speed to high. Continue beating as you add the rest of the superfine sugar in a slow stream.

Once the whites are very thick and glossy, beat in half the powdered sugar, gently pouring or spooning it by tablespoons onto the whites as you beat.

Once half the powdered sugar is beaten in, remove the beaters (tapping any whites clinging to the beaters into the bowl) then sift the rest of the powdered sugar onto the whites and, using a spatula, fold them in.

Add one teaspoon vanilla extract and fold it completely in.

I piped out and baked a little more than half of the vanilla meringue then folded in ½ teaspoon coffee extract to the remaining whites in the bowl for coffee meringues. You could add 1 to 1 ½ teaspoons coffee extract to the whole bowl of the whites for only coffee meringues.

To fill the pastry bag with the meringue, roll down the top half of the pastry bag, allowing you to spoon in the meringue down to the tip with smearing the meringue all up the sides of the bag. As you fill the bag with the meringue, just unroll the bag little by little as you fill it. The tall drinking glass gives you a place to hold the filled pastry bag upright as you do this.

Push the contents of the pastry bag down towards the tip until you see it; twist the bag above the level of the meringue to keep the meringue pushed down. Hold the pastry bag upright, guiding with one hand holding the bag near the tip, the other placed at the top of the contents (meringue) to gently push it out. Slowly push out “kisses” of meringue onto the pastry sheet, managing the size and thickness of each, releasing the hand pushing out the meringue then just lifting the bag away from the “kiss” pulling it off in a point.

Continue piping out meringues, leaving space between each to allow for them increasing in size during baking.

You can also just spoon out small meringues using a spoon.

Place in the oven and bake for one hour.

At the end of the hour, without opening the door, just turn off the oven and leave the meringues inside to finish baking and gradually cool as the oven cools, from one hour to overnight.

To keep the meringues crisp, store in an airtight container at room temperature. I like mine chewy, so I just wrap them in foil and keep them on the counter.

Thank you for subscribing to Life’s a Feast by Jamie Schler. Please leave a comment; your opinions and feedback help me create the content you want and your stories help build our community. You can support my work by sharing the link to my Substack with your friends, family, and your social media followers. If you would like to see my other book projects in the making, read my other essays, and participate in the discussions, please upgrade to a paid subscription.

Reading you is like history and poetry. An antidote for this chaotic world. Thank you

Delightful! Your posts are their own sort of confection.