What a fine comedy this world would be if one did not play a part in it. - Denis Diderot

Martin of Tours, Martin the Merciful, eventually to become Saint Martin, was born in Savaria in the Roman province of Pannonia - in what is today Hungary - in either 316 or 336 AD. At the age of 15, young Martin joined the Roman army, serving in the cavalry in Gaul, now France, soon finding himself in the region around Tours, very near where I live now. The legend surrounding this man, who would become, in time, the most celebrated Bishop of Tours and eventually one of the most known and recognizable Christian saints in France, is told and retold in innumerable written accounts and art works through the centuries. Martin, proudly riding towards the city of Amiens on horseback in the deepest of winter, splendidly attired in his cavalry uniform, chanced upon a beggar dressed only in rags. Martin, taking pity on the poor soul, drew out his sword and cut his cloak in half, giving part to the man to cover and warm himself. Some say it was prudence that made Martin keep half of his cape, needing to protect himself as well from the harsh winter; others say it was that only half of the cloak was his to give away, the other half the property of the Roman army. That night Christ appeared to Martin in a dream wearing the piece of cloak he had given away. This experience and the dream inspired Martin to leave the army, convert to Christianity, and devote himself to preaching. His thoughtful generosity and empathy towards the wayward vagabond earned him a sainthood.

As Martin is a local saint and one that this region, extending from Tours, where Martin lived, served as Bishop, and is buried, through Chinon to Candes (now Candes-Saint-Martin) where Martin died in 397, holds in such great esteem, there must be at least a bit of local folklore surrounding his time living here.

Ah, yes.

Martin with his donkey, his faithful companion, possibly his mode of transportation, traveled around the countryside spreading the Good Word to the villagers, peasants, and farmers. One day, Martin came across the locals tending to the grapevines - we are famously a wine producing region. The workers gathered around Martin as he preached; his donkey, with little to do but stand around and eat, began nibbling on the leaves of the vines, eating his way up and down the rows. That year, the vines produced the biggest, most lush, beautiful crop of grapes ever seen, and from then on, the peasants cut and trimmed the vines as Martin’s donkey had done. The saint’s beast taught the locals how to produce the best wine grapes, a true miracle!

As I wrote in a previous post, food (and wine) history is rich and abundant with stories. It’s often difficult to tell what is based on a truth and what is based on old wives’ tales, religious mythology, or just plain fancy. Like the story of why the macaron de Cormery is shaped like a belly button.

And this is where the monk comes in.

In Part 1 of Le macaron, I told you that the French did not begin to seriously cultivate almonds until about the 16th century. But the macaron de Cormery seems to have been created in 791 at the Benedictine Abbey of Cormery - founded by Ithier, an abbot of Saint-Martin of Tours - about 20 km south of Tours. If this is the case, then the macaron, a cookie made with the 3 simple ingredients of finely ground almonds, sugar, and egg whites, was not, in fact, first made in Italy but in France, thus this particular one from Cormery, said to be the actual first macaron, would have traveled south, been reproduced in a number of different forms throughout Italy, then returned to France centuries later with Catherine de Médicis.

The macaron was, in fact, a gâteau de voyage, a pastry that stayed fresh, moist, and tender for long periods of time, thanks to being primarily composed of sugar and almonds, making it the perfect food for extended voyages. So of course it would have been packed and carried along with travelers, sailors, soldiers, or members of religious orders going to, oh, I don’t know, maybe Rome?

The macaron de Cormery is made of ground almonds, both granulated and confectioners’ or powdered sugar, and egg whites, making it, like all the known variations of this popular cookie, tender on the inside with a slightly crispy outside. Don’t confuse the macaron with the macaroon which is dense and chewy; the macaron is light. What makes this specialty of Cormery particular is its shape.

Strangely enough, one odd story about how the macaron de Cormery got its shape wasn’t enough, for there are 2 conflicting legends about the cookie.

We know that simple cookies and pastries were often made in convents and monasteries, and the macaron was no different. The monks at the abbey in Cormery specialized in this “divine” treat, created by a certain Brother John, according to a 17th century poem that recounted the origins of the macaron de Cormery.

Brother John’s superior, Father Séraphin, was thrilled with the popularity of the tasty cookie, yet lamented "Something is missing for them to be perfect, and I know the reason: their shape is too crude, the customer must be able to recognise them and say on seeing them: There are the macarons that are from the monastery!"

Father Séraphin searching for inspiration, decided, as was his profession, to look for divine intervention, and resolved to pray to Saint Paul, patron of the abbey, for one whole night:

"When the sixth hour rings in the belfry,

To John's workshop I will go unsuspectingly...

The first object seen, I promise to God,

Will adorn the middle of all our macarons!"

While Father Séraphin prayed, Brother John worked, making macarons, putting tray after tray into the ovens, pulling tray after tray of golden macarons from the fires. At the stroke of 6:00, according to the tale, Father Séraphin went to the kitchens hoping that his prayers would work. He arrived at the door and bent down to peep through the keyhole; just at this moment, a spark flew out from one of the ovens’ fires and burnt Brother John’s robe right in the very center leaving "a hole edged with black, as round as a ring, not very big it's true but... you could see the skin!" Being always fearful of someone stealing his secret recipe, “Brother John, on hearing a noise, turned around showing the astounded father his portly monk's navel."

"That God, in his intentions, is therefore impenetrable!”, exclaimed Séraphin, as he realized that the monk’s navel was “The first object seen” and as he had promised to God, would from then on “adorn the middle of all our macarons!"

The second version of the story comes much later and Brother John is replaced by Brother Lai whose job it also is to bake for the abbey. Brother Lai, upset because the grand religious institution was getting poorer and less grand, prayed to the Virgin Saint. Suddenly, she appeared to the pious baker among the tender golden cookies he was preparing and praised the humble man, guiding him to look at the dough for a sign of what he should do to save the abbey from ruin.

Brother Lai got back to work. The kitchens, being hot from the flames of the ovens, he worked without his robes on, and as the poor man worked and worked, kneaded and baked, on and on, eventually fell asleep, exhausted, tumbling right into the pastry. He awoke sharply and, looking down into the dough, saw the outline of his belly button. Inspired, the good monk saw this as the sign and from then on shaped the macarons of Cormery in the round of his navel!

While the macaron de Cormery, the Navel of the World, as it is known, is like all other variations of this delicate cookie in that it is a crisp outer shell hiding a surprisingly tender, slightly chewy inside, it is unique in its shape. What is surprising is that it is related to the famed macaron de Paris, the colorful, more luxurious pastry we are so familiar with. Ground almonds, sugar, and egg whites. That’s it. The difference is in the quantities of these 3 basic ingredients and the manner of preparation. The macaron de Cormery is decidedly easier to make with much less risk of failure while creating a delicious, satisfying, more rustic cookie.

The macaron de Cormery contains equal parts granulated sugar and confectioners’/powdered sugar: the granulated sugar, which creates millions of microscopic air pockets, produces a dough with a light and airy texture; powdered sugar, being much, much finer, does not make those air pockets, thus producing a denser, sometimes crumbly, sometimes chewy texture. The combination of the 2 sugars gives a cookie that is super tender, melt-in-your-mouth, and slightly crumbly, slightly chewy, making the perfect macaron.

Le Macaron de Cormery

Fresh from the oven, these macarons are light and tender; left overnight, the macarons become satisfyingly chewy. Truly perfect either way.

Makes about 14 cookies

7 ounces (200 grams) finely ground almonds

½ cup (100 grams) granulated white sugar

Scant ½ cup (50 grams) confectioners’ (powdered/icing) sugar

2 ½ ounces (70 grams) egg whites, the whites of about 2 large eggs

½ teaspoon bitter almond extract

Stir or whisk together the ground almonds and the 2 sugars in a mixing bowl until blended and without lumps.

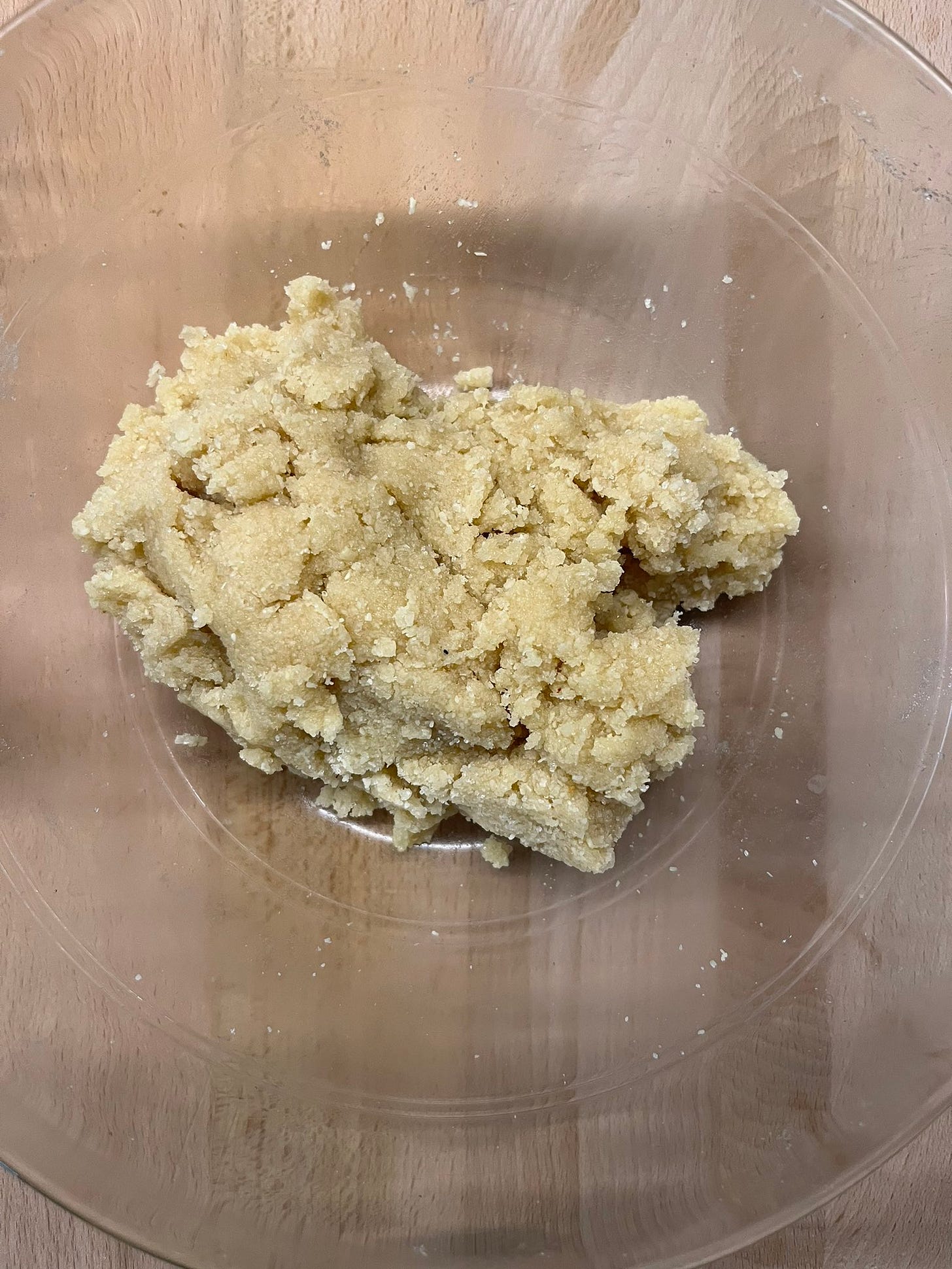

Using a fork or a spoon, blend in ¾ of the liquid egg whites; this will take a bit of time and work… it might seem that there isn’t enough liquid but there is, just keep stirring and, if you like, kneading the dough until all of the dry ingredients are moistened and a dough comes together - the dough might not yet be soft and smooth but don’t worry. Scrape the dough together, cover the bowl, and place the bowl in the refrigerator for 2 hours.

Preheat the oven to 475°F (250°C) - my oven only goes up to 250°C and you want a very hot oven.

Line a baking sheet with ovenproof parchment paper. Prepare a pastry bag with a large star tip.

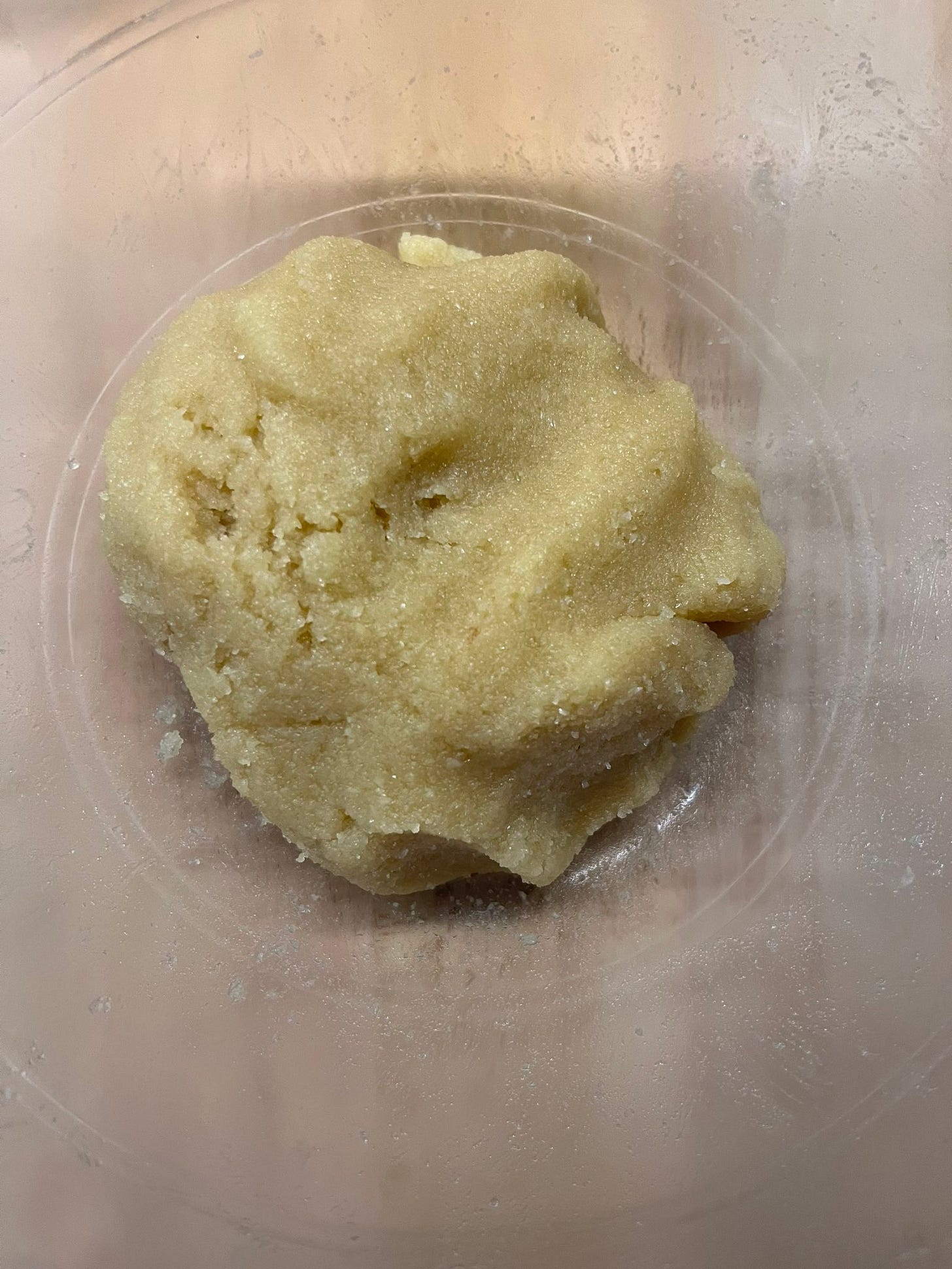

Remove the macaron dough from the refrigerator. Stir the almond extract into the remaining egg whites and add the whites to the dough in the bowl. Stir or knead until all of the liquid whites are incorporated into the dough, which should be smooth and tender.

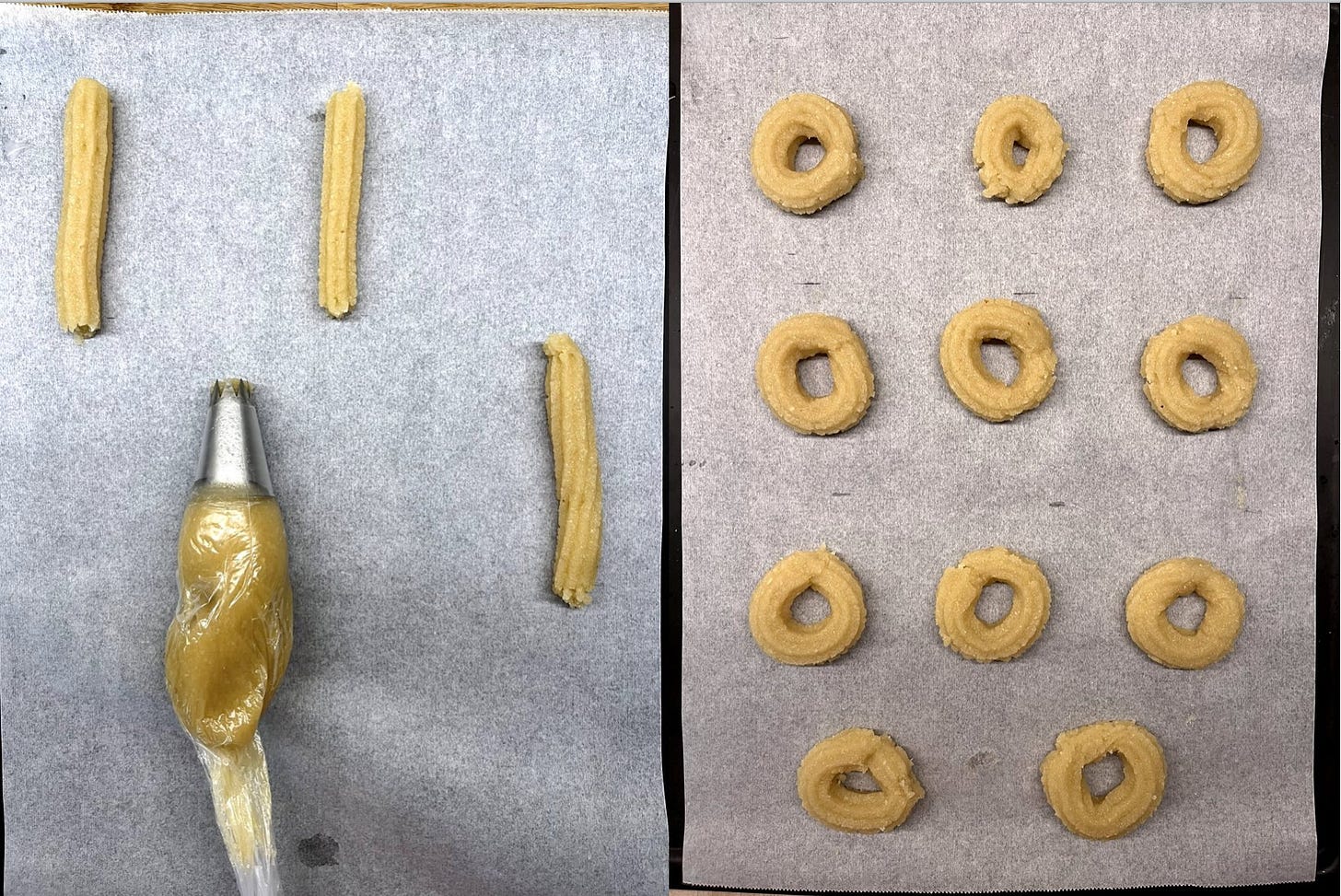

Pipe out 4-inch (10-cm) or just slightly longer tubes of dough, trying to keep the thickness of each tube regular - the star tip giving the tubes of dough the cookie’s distinct grooves. As the dough is very thick and a bit stiff, this will take a lot of patience and muscle! To help, I “glued” the parchment paper down to the baking sheet with a couple of tiny dots of the dough so the paper didn’t move while I piped.

Gently shape each tube into a circle, gently pushing or pressing the ends together to make a ring.

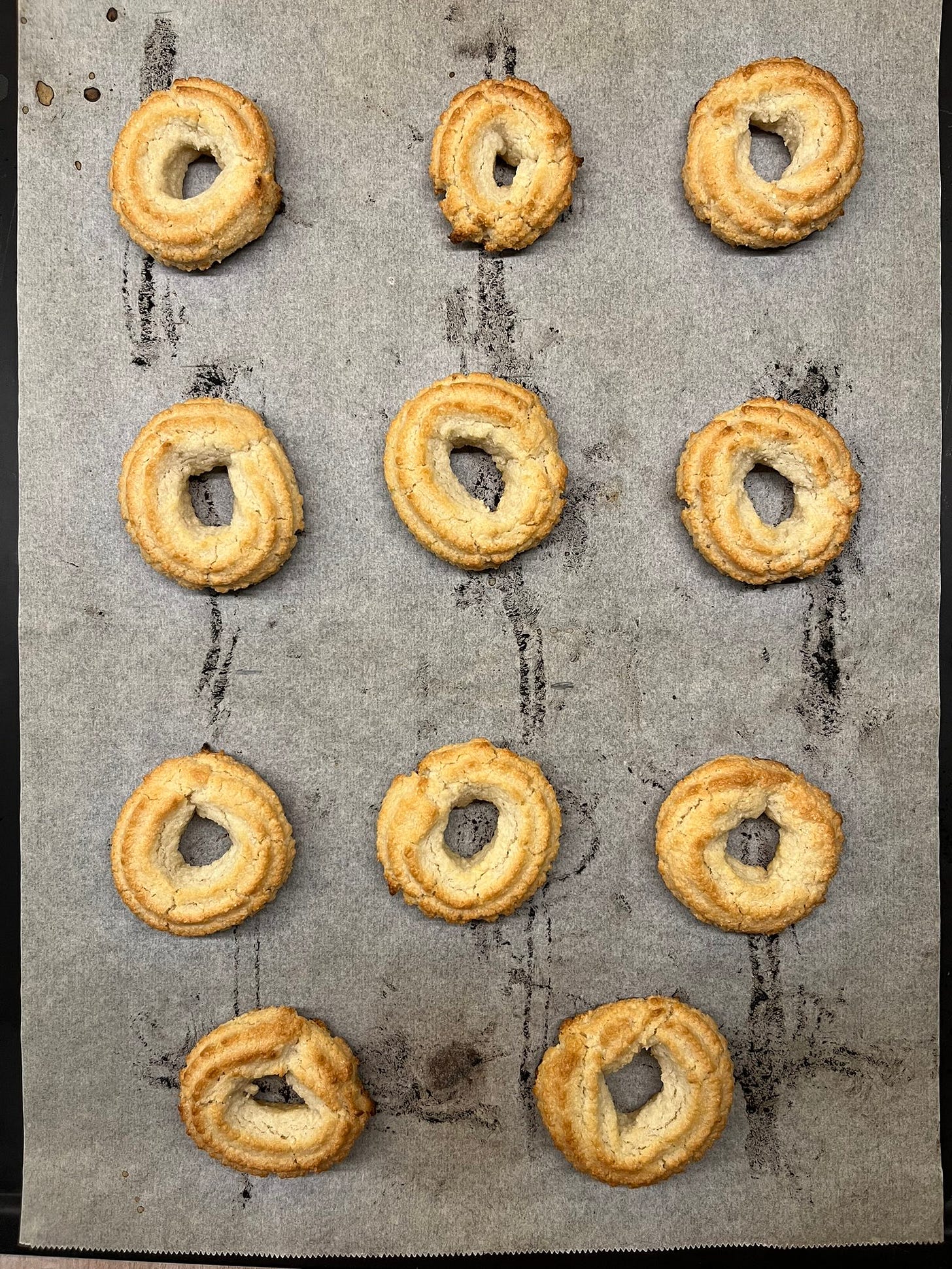

Place the baking tray in the very hot oven and bake only for 5 to 8 minutes until golden brown; if the cookies are left in the hot oven even a couple minutes too long the bottoms of the cookies may burn - although the cookies will still be delicious!

Remove the baking tray from the oven and gently left the cookies from the paper and allow to cool on a rack or plate.

Thank you for subscribing to my Substack, Life’s a Feast by Jamie Schler, where I share my recipes, mostly French traditional recipes, with their amusing origins and history. I’m so glad that you’re here. You can support my work by sharing the link to my Substack with your friends, family, and your social media followers. If you would like to see my other book projects in the making, read my other essays, and participate in the discussions, please upgrade to a paid subscription.

Really, Jamie, your newsletters are like reading chapters of a deeply researched and meticulously edited book. A real treat.

I loved these stories. Thank you!