Life is either boredom or whipped cream. - Voltaire

“Take a pottell of swete thycke creame

and the whytes of eyghte egges, and beate

them altogether wyth a spone, then putte

them in youre creame and a saucerfull of

Rosewater, and a dyshe full of Suger wyth all,

then take a stycke and make it cleane, and

than cutte it in the ende foure square, and

therwith beate all the aforesayde tbynges

together, and ever as it ryseth take it

of and put it into a Collaunder…”

Long before voluminous swirls of crème Chantilly began transforming simple treats — strawberry shortcake, pumpkin pie or apple tart, scoops of ice cream, choux puffs or éclairs, bowls of fruit, mugs of hot chocolate, or, dare I mention, a lover’s body — into indulgent experiences, Europeans were whipping cream into what they called “snow”, snowe in Great Britain, neige in France, neve in Italian. It wasn’t a topping or a filling — it was the dessert itself.

A Proper Newe Booke of Cokerye, anonymously written and published in England in 1545, is said to be the first written recipe for this now-popular delight, whimsically titled A Dyschefull of Snowe, a curious combination of cream, egg whites, cooked apple purée, and sugar. In 1552, François Rabelais mentioned neige de crème, cream snow, in the French classic novel The Fourth Book of Pantagruel's Heroic Facts and Declarations, while during the same epoch both French cookbooks Le Grant Cuysinier de Toute Cuysine (Jehan Bonfons, 1547) and Livre Fort Excellent de Cuysine Tresutile & Proffitable, 1555, offered recipes for “snow” - neige en romarin (snow with rosemary) in the first, neige contrefaicte (fake snow) in the second. Cristoforo da Messisbugo, grand chef for the House of Este during the Renaissance, included a recipe for lattemelle (or lattemele) mixed milk, in his Banchetti Compositioni di Vivande (Banquet Composition of Food) in 1549 while his fellow Italian Bartolomeo Scappi offered the first recipe for neve di latte, milk snow, alongside his latte mele in 1570 in his work Opera, including an illustration of the cold room of a kitchen in which cream should be beaten.

We’ve seen this word used in French before to describe both whipped or beaten egg whites and meringues: “The first appearance of “this small pastry” (meringues) in a French cookbook was in Lancelot de Casteau’s Ouverture de Cuisine in 1604. He called them neige seiche (sèche) or dried snow - here you must understand that egg whites whipped and beaten until thick, firm, and white are called neige - blancs montés en neige (“whites whipped/increased to snow”) - neige the French word for snow; correctly done, the whites will definitely look like pure white, tall and billowy snowdrifts.”

Lancelot de Casteau’s neige seiche are sweetened egg whites baked into meringues, but his neige is quite simply fresh cream beaten for half an hour - by someone who has most likely built up both muscle and stamina for such kitchen chores - then allowed to drain, finally scooped into small dishes, and topped with a branch of rosemary. He seems to serve neige both during dessert service with fruits, tarts and cakes, and alongside meats with cooked fruits as a condiment.

It took me ages to begin writing this post on such an uncomplicated, straightforward dish. Whipped cream. That’s it, just whipped cream. I couldn’t figure out how to dive into the topic nor how to make it either entertaining or engaging. Whipped cream has become such a common thing, and the simplest of concoctions, just cream and sugar. So what is there to tell? As long as man has milked cows and allowed the milk to sit, the cream would rise to the top, creating a thick mass that could be eaten as is, like a soft cheese, or whipped to create a lighter confection, the natural sweetness of the cream all one needed to flavor it (my cheesemonger told me “taste this cream before you add sugar so you know what real cream tastes like!”). Although sugar was a most natural companion when fresh herbs weren’t.

But like all culinary fare that has been made since the beginning of time, or once man (or woman) understood that this single ingredient could be beaten with branches in order to transform its consistency, there is a certain fascination in observing the evolution across the centuries.

It’s believed by many that François Vatel, 17th century French pastry chef, steward, and maître d’hôtel (head of household) was responsible for inventing crème Chantilly; as General Inspector of the Royal Table for the Prince de Condé at the Château de Chantilly, Vatel was responsible for the organization of receptions and dinners as he had formerly been at the Château de Vaux-le-Vicomte for Nicolas Fouquet. He oversaw exceptional fêtes and banquets, from choosing the menu and ordering ingredients through to perfectly orchestrating the serving of the meal to dozens of illustrious guests, often throughout many rooms. Madame de Sévigné wrote of Vatel “It was, after all, Vatel — the great Vatel — former maître d'hôtel to Monsieur Fouquet, and now serving Monsieur le Prince — a man of exceptional ability surpassing all others, whose brilliant mind was capable of handling the cares of an entire State.” At a particularly sumptuous banquet for the inauguration of the Château de Chantilly in the presence of the king Louis XIV and his Court in 1671, Vatel served crème fouettée, whipped cream. Evidently, the King, the Prince, and the entire Court were captivated—this exquisite preparation left such an impression that it found its way into several notable correspondences of the time and secured a lasting place in culinary history.

(The success of his whipped cream wasn’t enough to outweigh the perceived (by Vatel himself) mistakes made during this dinner and he finished the night by committing suicide in his bedroom, a sword blade through his heart.)

There is no definitive historical record naming a specific individual who first dubbed the whipped cream served at this banquet "crème à la Chantilly” but we do know that Joseph Menon was the first to include a recipe for Fromage à la Chantilly following his recipe for Mousse à la Crème in 1750 in La Science du Maître d'Hôtel Cuisinier, close to a century after it was served to a King and deemed worthy of such prestige branding. Both recipes are for cream whipped up high, the mousse à la crème using “a pint of good cream,” most likely single cream, and “foaming up” while the fromage à la Chantilly is made with “a pint of good double cream” and whisked until “bien montée en neige autant que des blancs d'oeufs que vous fouettez pour faire les biscuits à la cuilliere” - “as much as you whisk egg whites you whip to make sponge-cookies.” He suggests, as do other cookbook authors, beating the Mousse à la Crème with egg whites if “the cream doesn’t foam up as desired,” a recipe we will find a century later as a crémet nantais or crémet d’Anjou.

Strangely enough, La Veritable Cuisine de Famille par Tante Marie, published in 1925, has a recipe for crème fouettée with “ou fromage à la Chantilly” in parentheses, close to 2 centuries later. Chantilly cheese.

It was André Viard, who first used the term crème à la Chantilly, writing “fill them (choux puffs or tartlets) with whipped or Chantilly cream (crème fouettée où à la Chantilly) in the 1822 edition of his cookbook Le Cuisinier Royal. It does not appear in his earlier 1817 edition.

But I’m getting a bit ahead of myself. By the 17th century, whipped cream was already a familiar entremets — referred to in cookbooks as neige, snow, cresme façonnée (a distortion of the word foisonnée, meaning “to incorporate air bubbles by beating or whipping), or cresme/crème fouettée. Whatever it was called, it was served either unsweetened alongside savory dishes or lightly sweetened for dessert. As Joseph Favre noted in his Dictionnaire Universel de Cuisine Pratique (1905), “This type of cream—frothy, whipped into an emulsion—was already known to the Romans, who mixed it with honey and herbs.” In France, it was typically perfumed, if at all, with delicate accents like orange flower water, lemon zest, or coffee. It wasn’t until the mid-18th century, however, that the French began to expand whipped cream’s flavor palette, treating it as so many other desserts, folding in coffee essence or grated chocolate or infusing the cream with citrus zests, and fruit purées, mainly either raspberry or strawberry. Then along came Carême, who began, as he did with most other confections, flavoring whipped cream in earnest—experimenting with liqueurs, fruits, floral essences, nuts, coffee, grated chocolate, and caramel, sometimes tinting the whipped cream in pink or green, and folding it into other preparations, like bavaroise, blanc-manger, pastry cream, etc, to create new creams and desserts.

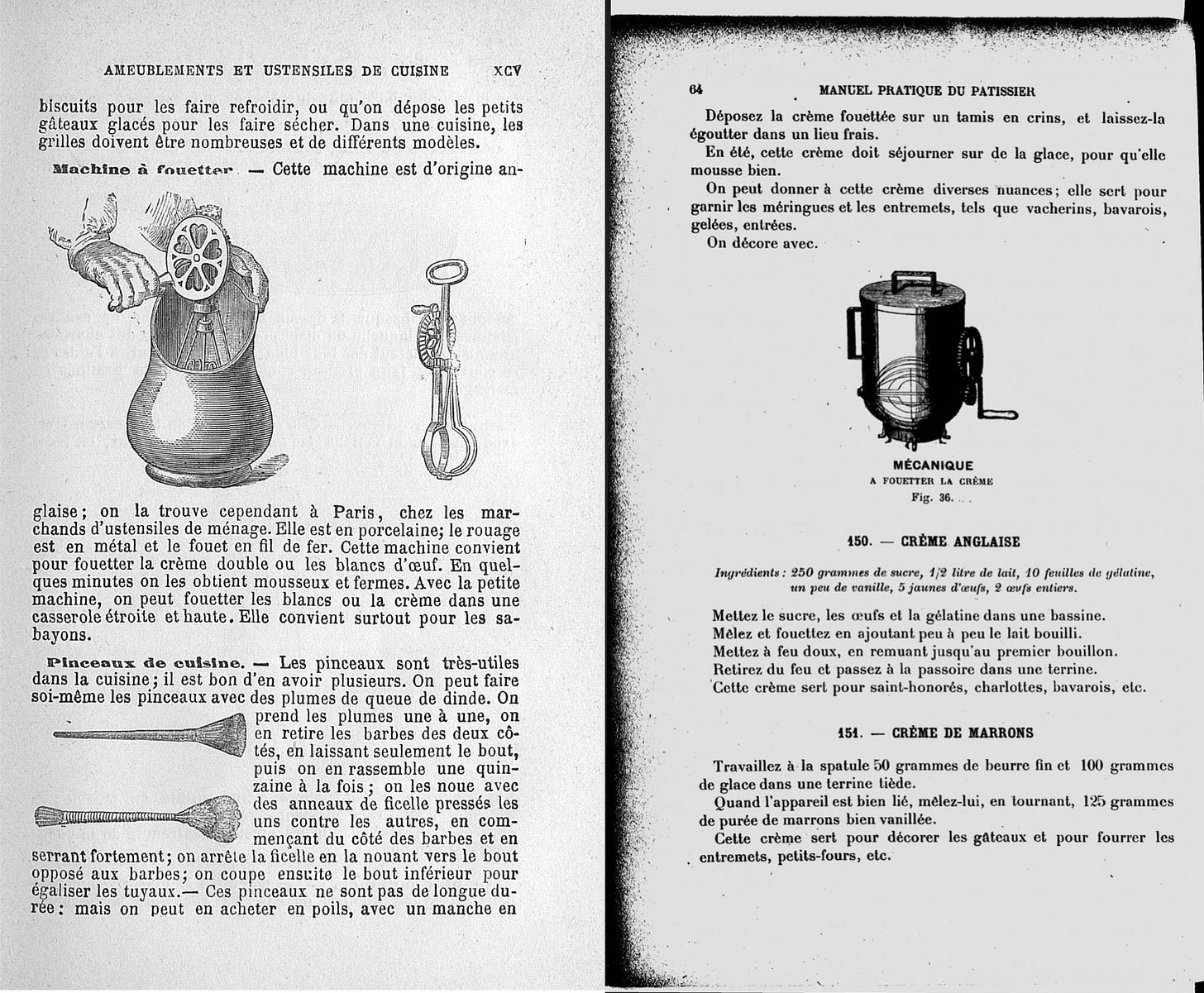

Whipped cream continued to be enjoyed much as it had been since the 16th century—as a dessert in its own right. But once Carême elevated it further, folding it into other creams to create richer, more velvety textures, adding depth and elegance to an already luxurious preparation, other chefs began seeing the extraordinary versatility of this preparation. Alexandre Dumas (Grand Dictionnaire de Cuisine, 1873) was filling choux puffs and éclairs with whipped cream, folding it into pastry cream, chilling it to make ice creams which were used for bombes and Bavarian creams, or filling lined molds to make charlottes, sometimes calling it crème fouettée, sometimes fromage fouetté à la Chantilly. Émile Hérisse (Manuel Pratique du Pâtissier-Confiseur-Décorateur, 1894) also used it to garnish meringues and other entremets such as vacherins, bavarois, gelées, and bombes. It is also, finally, used to decorate other desserts. And Hérisse includes an illustration of a machine to beat cream, as did Urbain Dubois in Nouvelle Cuisine Bourgeoise in 1888.

And yet, crème fouettée had always been and continued to be served as a dessert: “Then cast your Snowe uppon the Rosemarye and fyll your platter therewith.” (A Proper Newe Booke of Cokerye, 1545); “Arrange it on a dish, sweeten it well, and drizzle good scented water over the top.” (Nicolas de Bonnefons, 1654); “Fill your gobelets, and do so as generously as possible; the goblets in which it is placed should be beautiful and grand in scale.” (Joseph Gilliers, 1751); “Arrange in a pyramid on porcelain and garnish all around with berries.” (J.J. Machet, 1803); “Arrange the cream in a pyramid or flat; smooth it out well with a knife. When you're ready to serve, garnish with coloured sugar, or sprinkle with a thin lemon, and serve.” (M. Gauthier, 1827); “Whipped cream should be served in a bowl with a drizzle of sweet cream around it.” (Dr Jourdan-LeCointe, 1844); “Arrange on a cold platter and serve with a plate of cookies or biscuits.” (Urbain Dubois, 1888); “Sweet, violet-flavored Chantilly cream, lightly frappéed, spooned into elegant crystal cups.” (Auguste Escoffier, 1912); "Arrange the cream in a domed shape in a bowl or compote that has been chilled in a refrigerator.” (Entremets et Boissons Glacés, c. 1929). As Nicolas Bonnefons noted in 1654 writing about cresme façonnée “when the cream begins to rise is the most pleasant and healthiest of all.” People have always found it luxurious and healthful in its graceful creaminess, its featherlight airiness, its natural sweetness, so it was never treated as a mere garnish—it could stand alone as dessert in its own right.

Whipped cream, crème fouetté, became so synonymous with ethereal lightness, something evanescent, all air and delicacy, that the term became a figure of speech denoting something, a work, a book, a speech, even a person, where one finds only fine words, brilliant appearance, outwardly lovely, impressive, and refined, “but where there is no substance, no solidity”… “by a metaphor taken from cream, which swells prodigiously, when we whip it.” (Antoine Furetière, Dictionnaire Universel, 1702) and “It's only whipped cream”. (Dictionnaire de l’Académie Française Tome 1 - 1835

Chefs saw crème fouettée or crème Chantilly as something unique and fascinating, consistent enough, exceptional enough to serve in cups or bowls, or in pastry shells, simple or almond flavored, as cream tarts as far back as Joseph Menon, in fragile choux puffs as did Viard and Dumas, in puff pastry cups like Carême, or, as Pierre Lacam mentioned, en cornet (in a cone like ice cream). But one had to have access to the best cream possible. “Of all the sweet cold entremets, Crème à la Chantilly is the simplest to prepare,” wrote Baron Brisse in 1844, “but only if you have double cream worthy of the name, which is difficult to do in Paris. So I'm giving the recipe mainly for the province.” In 1900, Lacam published Le Mémorial Historique et Géographique de la Pâtisserie in which he stated “All the cities of France are overflowing with cream, but here in Paris, it’s nearly impossible to get any in its natural state; the ice cream makers have claimed almost all of it,” complaining how challenging it was to procure the necessary cream so one could whip up crème à la Chantilly.

So is it whipped cream or Chantilly cream? Even as late as 1934, someone as illustrious and influential as Auguste Escoffier was writing “crème fouettée dite crème Chantilly” in his huge tome Ma Cuisine. Françoise Bernard was writing crème Chantilly ou fouettée as late as the 1980s. Finally, my 2 huge professional pastry manuals from École Ferrandi and Marabout both have, simply, Chantilly. But I’m guessing that you could ask for either one in a French restaurant or ice cream shop and you’ll be served.

Crème Fouettée or Crème Chantilly

There is really no recipe, just the best cream you can get, double cream or whole (heavy) cream for whipping. Powdered sugar. A small amount vanilla extract.

Unless you’re adding a liquid flavoring (a liqueur, some orange juice, etc), you’ll want to add a few tablespoons whole milk or liquid heavy cream if using thicker double cream for this.

Double cream will produce a much thicker, denser whipped cream like mousse, single/ heavy/ whipping cream will give you a softer, more fragile whipped cream (which must be eaten more quickly). Mascarpone is a good substitute for double cream; add the quantity milk or liquid cream as needed to lighten the mascarpone as you whip.

If you like, you can add coffee or orange essence, citrus zest, grated chocolate, a small amount of liqueur. You can also dissolve some instant coffee powder in the milk or heavy cream; if you have to gently heat it, just refrigerate until cold before using.

1 cup (250 ml) double cream

3 tablespoons liquid heavy (whipping) cream

½ teaspoon vanilla extract

3 - 5 tablespoons powdered/icing sugar, sifted and to taste

Start by chilling a bowl and the beaters (hand or stand mixer) in the refrigerator for at least half an hour.

Pour the cream into the bowl and beat until it begins to thicken; add a splash of vanilla extract or other essence and continue beating. Once soft peaks begin to hold, add the milk or heavy cream and continue beating then add a tablespoon or two of the powdered sugar, sifting the powdered sugar onto the cream to take out any lumps. Once your cream holds stiff peaks, add more sugar to taste.

At this point, you can fold or quickly beat in grated chocolate or fruit purée a little at a time, avoiding adding so much purée the cream turns back to liquid.

Either serve immediately or chill until ready to serve.

Serve as you would a mousse; and serve with berries.

Thank you for reading and subscribing to my Substack Life’s a Feast. Please leave a comment, like and share the post…these are all simple ways you can support my writing and help build this very cool community. If you would like to further support my work and recipes, please consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Sadly, Americans have relegated whipped cream to the Department of Garnishes. The history of whipped cream is fascinating. Thanks!

OMG- You’ve just written a book 📕 I confess-I prefer La Crème.

I will take some leisure time to read thru your post…then attempt to make it after this busy few wks.

Thanks for not being political- pleasant change👈💕🇺🇸

Hope you’re doing well👏🇫🇷