The Creator, by obliging man to eat in order to live, invites him to do so through appetite, and rewards him with pleasure. - Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin

The French have always loved things wrapped in pastry. Who doesn’t? But it’s a real specialty with the French. Tourtes have been popular from the earliest days of the kingdom, recipes offered in the earliest cookbooks. Rissoles were a wildly popular treat in the Middle Ages; rissoles were little hand pies or mini tourtes, mostly savory, sometimes sweet, sometimes baked but mostly fried, and their popularity continued well into the 19th and early 20th centuries. Pastés - I imagine from whence the word pastry came (or vice versa), a pie baked at the pasticier, in the village pastry shop’s oven - were also tourtes or two-crust tarts, again, often savory and yet best known as filled with pears. Tourtes, pastés and rissoles were made from regular shortcrust pastry, pâte brisée, until the invention of puff pastry in the early 17th century, when more and of these meat, fish, vegetable, or fruit pastries were made in the lighter, flakier, richer crust. Small pastries, tarts or tourtes, were often a way to use up bits of leftover puff pastry from larger confections.

And then came the chausson. A chausson is, according the the 1938 Larousse Gastronomique, simply “a preparation made from a round sheet of puff pastry, filled with a composition of some kind, folded on itself, and baked.” A turnover. Chaussons are both large and small and filled with basically any kind of savory or sweet filling. The larger chaussons, were considered rustic, family fare, while the individual chaussons are a bit more elegant, what we commonly find in boulangeries today filled with applesauce or apple compote, and would generally come much later in the pastry’s history.

It is thought that the chausson aux pommes (the apple turnover) was born in the city of Saint-Calais, a small city situated between Le Mans and Orléans. An epidemic, either the plague or dysentery, it is still debated, swept through the town in the year 1630 (some say earlier). According to legend, the châtelaine, the mistress of the château of Saint-Calais, distributed apples and flour to the population, pushing a wheelbarrow filled with these goods from door to door; the people were able to make pâtés aux pommes, small tarts of apples covered or wrapped in a simple pastry crust, and thus were the good people of Saint-Calais saved. The pâté aux pommes became the chausson aux pommes, and now the city hosts a yearly celebration of the event, selling chaussons to commemorate the “miracle.”

While a pâté aux fruits, still found in certain fruit-growing regions today, is round, the chausson is not. Curiously, the chausson, also the French word for slipper, was commonly used in cookbooks throughout the centuries to describe foods that began round which were then to be folded into a half-moon shape, from omelettes to rissoles. The word chausson has a curious and surprising origin: chausson is derived from chausse (formally called hauts-de-chausse), as are the Picard cauchon, Spanish calzones, and Italian calzone, of a similar shape. Chausse or hauts-de-chausse were mens’ breeches or pantaloons, specifically those worn in the 13th through the early 17th centuries, breeches that covered the body from belt to knee, usually puffed, traditionally vertically pleated or banded. There was often a lacy ornamental band at the bottom of the breeches at the knee. If one looks at a chausson aux pommes, one can see the corresponding elements: the poofy contour, the bands in the distinctive decorative lined markings, and the lacy edging.

In 1893, François Bouquet republished the 16th century poem La Parthénie by Baptiste Le Chandelier in which is the mention “crepidula polentaria.” Bouquet translates this curious name as a “chausson en griote sèche” or “gruau" (polenta), claiming crepidula is a diminutive of crepida, or a “gâteau frit ou gâteau farci” - a fried or stuffed pastry, saying “we still give this name to a type of pastry, confirming this with his translation of the following lines “that he knows how to give a thousand shapes to dough made with the gifts of Ceres, such is the variety of his art.” Crepidula is a variety of sea snails or marine mollusks commonly known as the slipper snails, slipper limpets, or slipper shells, coincidentally in the shell shape recreated, knowingly or not, by pastry chefs for the chausson aux pommes.

But while we can only guess as to the origin of this pastry and its curious name, the first actual mention of a chausson was in François Pierre de La Varenne’s 1653 cookbook Le Pastissier François. His recipe is for “une tourte ou pasté, ou chosson de pommes ou de poires, ou d’autre fruit crud.” In other words, one rolls out the pastry dough to any size or shape one likes, making either a tourte ou pasté, ou chosson. One then dusts the pastry with sugar, then layers one peeled and cored apple or pear (“or other raw fruit”), a bit of fresh butter, a dash of cinnamon, then the filling is covered with another piece of pastry, and, finally, baked. He suggests one can also add pine nuts, raisins or sultanas, prunes, or thin slices of lemon zest.

And then it becomes difficult, indeed, to find a mention of a chausson as a turnover, fruit or otherwise, for quite a long time. Jam and fruit tarts were popular, and puff pastry was often the crust of choice. Pierre de Lune has several ways to make a tourte de pomme, and 2 recipes for tourte de crème de pommes; crème de pommes, apple “cream” being, of course, applesauce made from apples cooked in white wine with cinnamon and sugar (and a bit of chopped candied lemon peel, if one likes), until soft and smooth. One recipe layers the applesauce between 2 thin puff pastry crusts, brushed with an egg wash to create a golden top crust when baked, then sugared before serving.

In the 1746 La Cuisinière Bourgeoise, Joseph Menon has recipes for tourtes de toutes sortes de confitures pour l’hyver (hiver) and tourtes de confiture pour l’été - two-crust jam pies for winter and for summer - puff pastry tarts filled with jam, the top crust laid on in strips like a lattice crust; one can, he suggests, make the same using fruit compote or purée. He also makes a filled cake, a gâteau fouré, in which two rounds of puff pastry, rolled out thinly, are stacked one on the other with a layer of fruit jam in between, the top is brushed with egg wash and the cake baked until golden. Once baked, the top can be dusted with sugar and iced with a hot iron. Very much like a chausson, except, of course, for the shape.

By the 19th century, the word chausson is found in cookbooks quite often, used not for a particular pastry, but for the technique and finished shape of other things, most commonly for omelettes or, yes, rissoles: “en forme de chausson” or “in the shape of a chausson.” It was common to find the instructions “Repliez-la sur elle-même en forme de chausson et mettez-la sur le plat” or “fold it on itself to form a chausson and place it on the dish”. Philippe-Edouard Cauderlier suggests “using the puff pastry trimmings of his little vols-au-vent (petits vidés - or “little empties”) to make individual pastries filled with a bit of jam or almond paste, the edges of the round of pastry then wet, folded over on itself and sealed “in the shape of a chausson” while not calling the pastries themselves chaussons.

It isn’t until the very end of the century that we finally see recipes for chaussons, even as the Dictionnaire de l’Académie Française offers this definition for chausson: “Still used to describe a pastry containing marmalade, compote, or jam, and which is made from a round pastry crust folded onto itself” in 1835. “Still” meaning, in my idea of the word, that it is an old pastry, one known and made for a long time, even though we have never seen a recipe for one in a cookbook, other than La Varenne in 1653. And yet, the word is commonly used to indicate a culinary technique, especially for rissoles, which continue to appear in cookbooks, a small pastry made now from puff pastry enclosed around a filling, sweet or savory, and folded in half “to give them the form of little chaussons.” Could this indicate that the chausson aux pommes was a rustic treat made and sold by bakers, so common that it didn’t deserve a spot in a cookbook? Yet the same can be said for rissoles. We might never know. But if the August 31, 1889 issue of L’Art Culinaire journal is any clue, the recipe for cervelles en papillotes (parchment-wrapped brains) instructs one to fold and seal the papillotes “the way one makes chaussons de pommes.” Maybe they were just too common and…common…to ever be offered a spot in a high-end cookbook.

And then, in 1876, Urbain Dubois has a recipe for chossons aux pommes in his book L’École des Cuisiniers, curiously the same spelling as François Pierre de La Varenne two centuries earlier. Even more curiously, he gives a detailed explanation on the folding process and shaping of his pastry, instructing to fold the pastry, “forming a large rissole” flipping what we normally read on its head!

At last, Auguste Colombié offers us a recipe for chaussons normand aux pommes in his 1906 La Pâtisserie Bourgeoise. Colombié’s chausson is a single large one, not smaller, individual pastries - and normand because the French region of Normandy is famously known for its apples. His chausson is filled not with compote or applesauce, but with thin slices of peeled and cored apples which are then dusted with sugar. M. Colombié published the same recipe in the October 1, 1905 issue of the monthly professional revue, La Pâtisserie Bourgeoise. Emile Darenne and Emile Duval’s chausson aux pommes - also one single, large one - included in their Traité de Pâtisserie Moderne a few years later is filled “with apple purée (marmalade de pommes) or, depending on the occasion, finely sliced apples sprinkled with vanilla sugar.”

By the 20th century, chaussons aux pommes were a simple enough treat to make at home for the family - “pâtisseries vite faite et bon marché” - “quick and inexpensive pastries” - whether making one’s own puff pastry or not. All one needed was the dough, apples, sugar, and cinnamon, if one wished. Books like La Cuisine de Chez Nous (Our Home Kitchen, Dory), 1930, 800 Recettes de Cuisine Pratiques, Simples, Économiques (800 Practical, Simple, and Economical Recipes, Pichard et Poirier), 1942, La Cuisine Familiale (Family Cooking, Pellaprat), 1955, Petit Guide de l’Alimentation Familiale (Little Guide to Family Food, Serville), 1964, and La Cuisine Familiale (Family Cooking, Mariette), 1975 all have their recipes for chaussons aux pommes. And if one doesn’t wish to make them at home, they are easily found in every boulangerie in France.

If you like apple turnovers (chaussons aux pommes), ladies, don't overdo it. Common sense and art are needed, even in apple turnovers. Gluttony punishes the glutton. - Victor Hugo, Les Misérables

Chaussons aux Pommes - Apple Turnovers

For about 8 or so chaussons.

After making my pâté de pomme de terre (potato tart), I had half a batch of puff pastry left, about 1 pound or a bit more (500 - 600 grams). I made two batches of chaussons aux pommes with this leftover puff pastry with 8 chaussons in each batch, each using half of the rest of the pastry (a quarter of the original block of pastry) and 3 largish apples for the filling for each batch. You can easily double the quantity of both the puff pastry and the filling.

Puff Pastry

¼ block of homemade puff pastry following my recipe, about 17.6 - 21 ounces (250 - 300 grams) - find the recipe on my Substack post Pâte Feuilletée - or the same weight of really good quality, all-butter store-bought puff pastry. Use the pastry chilled from the refrigerator.

Apple filling

3 - 4 apples - you want to use a variety of apple that cooks easily into purée, not a variety that holds its shape when cooked. You want fruity apples, not tart apples. The best apples I’ve found for chaussons aux pommes are Canadas.

1 ½ or 2 tablespoons (25 or 30 grams) unsalted butter

¼ cup (50 grams) granulated brown sugar

¼ to ½ teaspoon cinnamon

¼ teaspoon vanilla

A small cup or bowl with water and a pastry brush for sealing the chaussons

Egg wash

1 egg + 1 teaspoon powdered (icing) sugar

Preheat the oven to 400°F (200°C). Have ready a large cookie or baking sheet lined with ovenproof parchment paper.

Prepare the filling by peeling and coring the apples (whatever method you like best), and cutting the apples into chunks.

Heat the butter in a large frying pan or sauteuse; when the butter is melted and sizzling, add the apple chunks, the brown sugar, and the cinnamon and stir to combine and to coat all the apple chunks with melted butter. Stir in a dash of vanilla, if you like. Cook the apples for 10 or 15 minutes over medium-low heat, stirring often, until very soft; you want to be able to crush and purée the apples until smooth using just the back of a fork. Remove from the heat, scrape the cooked apples into a bowl and purée.

Roll out the puff pastry on a floured work surface to a thickness of ¼ inch (1/2 cm); brush off any excess flour. Cut circles of dough about 4 ½ inches (11 cm) in diameter - I use a stanless (metal) pastry ring mold which cuts the dough cleanly. You should get about 8 circles of dough with this amount of pastry.

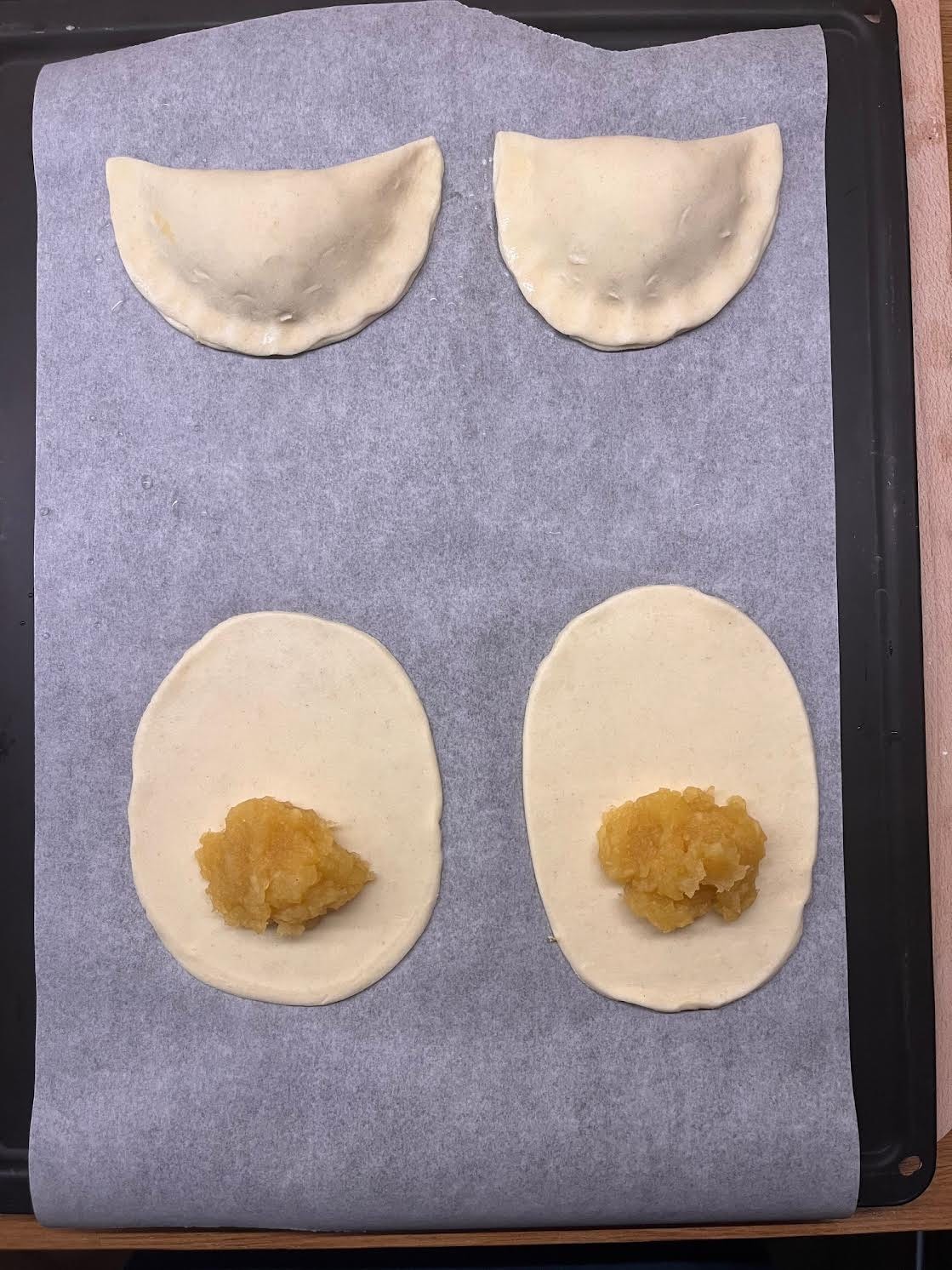

Using a rolling pin, roll the circles of dough out gently just to create an oval shape (which will also then the dough just enough) - see the photo.

One by one, place an oval of dough on the lined baking sheet and place about a heaping tablespoon or a bit more of the applesauce on the lower half of each oval, leaving about an inch (2 cm) of dough around the sides and bottom of the mound of fruit - see the photo.

Lightly brush the outer inch of the dough all around the edges of the oval with water, lift the top half of the dough over the mound of applesauce, matching the edges of the dough together and press to seal the edges. I press the edges closed with my fingers then with a fork, creating that “lacy edge”.

Continue with all of the dough circles and the applesauce (any extra applesauce can be eaten straight from the pan) until you have 8 filled, folded, and sealed chaussons on your baking sheet.

Whisk the egg and the teaspoon of powdered/icing sugar together in a small bowl or cup until super well blended. Using a pastry brush, brush a thin coating of the egg wash all over the tops and sides of the 8 chaussons. Now, using the tip of the sharp blade of a knife, gently carve or draw the distinctive curved marking onto the surface of each chausson, being super careful not to cut through the dough or make any holes in the dough.

Bake the chaussons in the preheated oven for about 25 minutes. They should be a puffed, a beautiful deep golden brown color, and the surface should be shiny from the egg wash.

Remove from the oven and transfer the chaussons onto a cooling rack to cool until warm before eating.

Thank you for reading and subscribing to Life’s a Feast by Jamie Schler. Please leave a comment, like and share the post…these are all simple ways you can support my writing and help build this very cool community. Let me know you are here and what you think. You are so very appreciated.

Wow, these look delicious. My apple pie loving husband would love them, so I hope to try my hand at them soon.

My wife used to make the Normandy type, with thin apple slices. I think these are best. RIP Elodie, and thx