The Strange and Curious Forgotten Occupations of Paris

A little French food history that might surprise you.

Why travel far when the new, the strange, the extraordinary lies right at one’s doorstep - mere omnibus rides away? - Alexandre Privat d’Anglemont

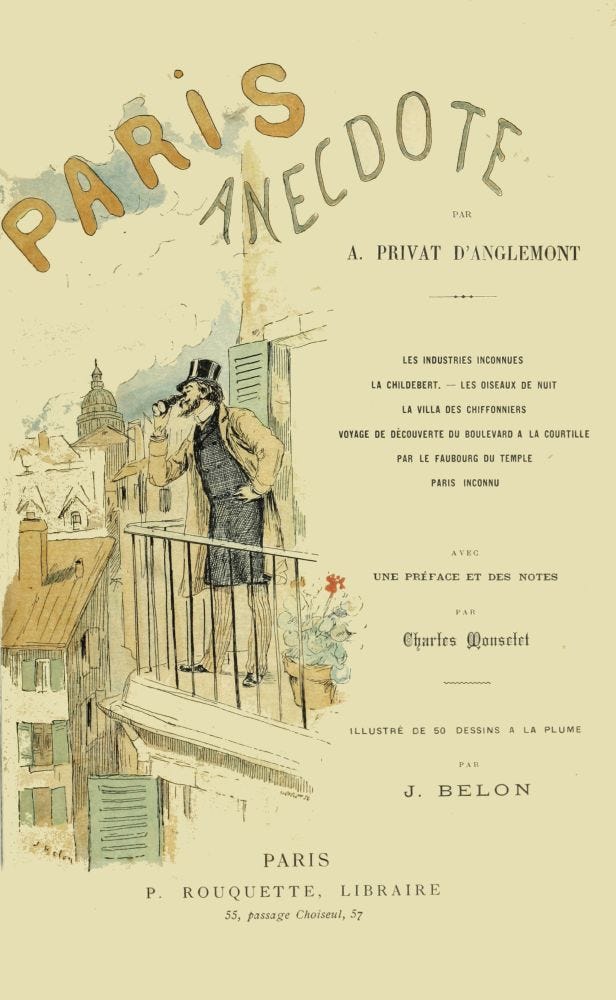

“Every day in the streets of Paris, you rub shoulders with thousands of passersby whom you pay no attention to whatsoever…. Have you ever been walking around Paris and wondered how all these people manage to make a living?” Alexandre Privat d’Anglemont, journalist, writer, and bohemian opened both his books Paris Anecdote (1854) and Paris Inconnu (1861) with this deceptively simple - yet profound - question. Who else but a true observer would take the time to study the people scurrying through the streets and alleyways of 19th-century Paris and wonder how they lived, earned the few francs they needed to eat and survive day to day?

Fueled by his curiosity about a populous yet largely invisible segment of Parisian life, almost in awe of the creativity and ingenuity of the poorest Parisians who lived by their wits to survive, Privat d’Anglemont explored the city’s back streets and underbelly, becoming a chronicler of the unseen and the resourceful ways they earned their bread. His book Paris Anecdote is a long rambling narrative, a series of intimate yet humorous sketches that paints a vivid portrait of the ‘industries unknown’ - the quirky, forgotten trades that thrived in the city’s shadows and along its bustling margins, some ingenious, some shady, all revealing a side of Paris rarely seen by the polite eye of his readers.

He was fascinated by the minutiae of Parisian life, the grand and the insignificant, every human being who made the city hum. He knew each of them had their place in this bustling city, a means of survival, a day-to-day life that, together, sustained it, keeping Paris alive and moving. “We saw such surprising things,” he wrote, “that we couldn't resist the urge to share them with our curious readers.” There are people, he continued, who embark on long and perilous voyages to see the extraordinary when just outside their door, or at the end of a short bus ride, they can discover the new, the bizarre, and the extraordinary at every turn, on any street. “We simply wish to give you an idea of the ingenious spirit of Parisians by reviewing the poor, hardworking, intelligent people who have managed to create an honest industry that meets the various needs of the public.”

Many of these strange and forgotten trades - and, unfortunately for M. Privat d’Anglemont, not all honest - will sound straight out of a Dickens novel (or Balzac or Dumas) rather than real occupations, but they existed. In a large, cosmopolitan city like the author’s 19th century Paris, and in the years before, necessity was indeed the mother of invention, and a multitude of curious, often practical, sometimes indispensable, occasionally dubious occupations flourished.

When my husband sent me the link to a copy of Paris Anecdote, I skimmed the pages for those tied to the food trade. Of course I did. Some of these old métiers I found awfully clever, others, well, rather frightening, a fine line between necessity and danger (or outright disgusting). Altogether, this peek into another world where hunger trumped hygiene, and the need (or desire) to save a few centimes could blur the line between industry and fraud, simply fascinates to this day. But it all kept the wheels of the economy turning, and served, in some strange way, to reduce food waste, and allowed the poorest to survive.

Many of these jobs were in close proximity or connected intimately to Paris’ tremendous, bustling Les Halles market; these odd professions helped feed the poorer population of the city while, wittingly or unwittingly, making use of what might otherwise have been discarded, thus, as we would say today, reducing food waste. While food and health inspectors did exist, some even uniquely assigned to Les Halles, along with officials charged with detecting fraud, such trades and professions nevertheless thrived, at least for a time, sustained by demand, the economic realities of a large metropolis, and the gaps in oversight that allowed fraud to flourish, often in plain sight. Les Halles was, after all, Le Ventre de Paris - “The Belly of Paris,” according to Émile Zola (1873).

I’ve decided to list a few of them for you, most taken from Alexandre Privat d’Anglemont’s funny little book, Paris Anecdote, some from other books or newspapers of the 19th century.

• Marchand des fraises des Halles - Strawberry seller of Les Halles

While they might have sold strawberries, this was the nickname given to petty (small quantities) sellers who would purchase the “tail-ends” of produce in and around Paris’ Les Halles market. This might be fruits and vegetables too advanced to sell, or the scraps, trimmings, or leftover parts of produce that couldn’t be sold at full price or at all - the wilted outer leaves of lettuce, carrot tops, bruised fruit, or the ends of beans, onions, or leeks. The marchand des fraises would resell, repurpose, or cook these tail-ends into simple dishes that they would then sell on to the poor. They might have even used their wiles to “freshen up” some of their salvaged produce, passing them off as fresh and fetching a higher price.

• Cuiseuse des légumes - Vegetable cooker

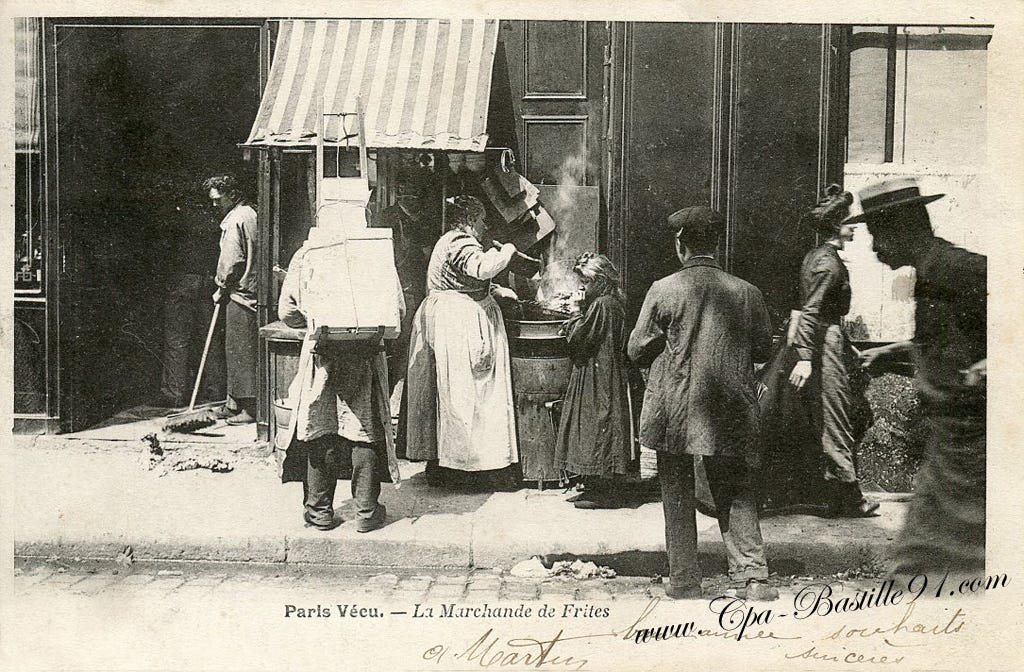

Often women, the cuiseuses des légumes, or vegetable cookers, made their living boiling or pre-cooking vegetables in bulk, then selling them hot and ready to eat in the markets or streets. Their customers were usually working-class Parisians, those without proper kitchens, or laborers and porters who needed something cheap and filling during the day. These vendors were part of a larger world of cuisine de rue (street cooking) that thrived in 19th-century Paris, long before the modern idea of “takeaway” meals or food trucks. Sometimes these women would collect or purchase vast quantities of fruits or vegetables, such as sorrel, chicory, spinach, apples and pears, or artichokes in season, and cook huge vats of them. The cooked fruits or vegetables would be sold on to restaurants, food shops, or market vendors, primarily because it would have cost these establishments more to cook the fruits or vegetables themselves than buy them already cooked. This wasn’t a trade open to everyone; the equipment was costly, as was the fuel and the initial purchase of the raw ingredients (unless scavenged), not to mention rent - one needed a large enough space to set up the equipment. Les cuiseuses des légumes often set up their stoves and vats in their homes to make it financially feasible. In the mid- to late- 19th century, the cuiseuses d’artichauts, the artichoke cooker, was a well known figure in the neighbourhood around Les Halles, working nonstop during the 4 months a year that artichokes were in season.

• Marchande de soupe - Soup seller

I wrote a short history of French onion soup on this Substack; I explained when and how this traditional soup became a classic Parisian brasserie and bistro staple. But before the recipe was enriched and sold in restaurants, it was a street food, simple, filling, and nourishing. Women would set up large tables on the sidewalks around Les Halles or rows of large pots or vats nestled atop portable stoves and serve bowls of soup to the “strongmen” of Les Halles market, local porters, waiters, vendors, laborers, or cops on the beat who needed a hot restorative during or after a day’s - or night’s - hard work.

Which leads us to the bijoutier (bijoutière) ou marchand(e) d’arlequins or the regrattier. One of my personal favorites. In Paris Anecdote, Privat d’Anglemont’s local character, “la mère Maillard” is a bijoutière d’arlequins creating dishes of randomly assembled foods sourced from restaurant plate-scraps (“rogatons”).

• Regrattier - Bijoutier (Bijoutière) - Food resellers

Common in the Middle Ages through the Old Regime, the regrattier (sometimes spelled regrettier) was a reseller who dealt in small portions of foodstuffs (salt, mostly, but also bread, butter, cheese, meat scraps, wilting vegetables, etc.). But they would also collect table scraps and leftovers from aristocratic and later upper class homes and sell them in smaller portions to lower-income urban populations. In the 19th century, the word bijoutier (or bijoutière for a woman) began being used for these merchants that would collect table scraps and leftovers from bourgeois homes as well as restaurants, arranging the food onto plates to resell to the lower class who needed a cheap but good meal. In older French, bijou - jewel - could mean “a trifle, or a small item” - and by extension, a bijoutier (jeweller) was a dealer in trifles, including edible odds and ends. I have a Dickensian image in my head of young food scavengers or older women standing on the street at the kitchen door of some great house holding a bucket into which a butler is scraping table scraps off of elegant dinner plates.

The bijoutière was a marchande d’arlequins, a seller of harlequins. Charles Virmaître defined the “arlequin” or harlequin in his 1894 Dictionnaire d’Argot Fin-de-Siècle (End-of-the-Century Slang Dictionary) as “scraps of all kinds of food that restaurant cooks sell to market vendors. These scraps are carefully sorted, and the vendors arrange them into assorted dishes that the poor buy for a penny or two. This expression comes from Harlequin's costume, which is made up of (patches of) fabrics of different colors.” The bijoutière or marchande d’arlequins would thus arrange the bits of food - table scraps from restaurants and upper class homes, or bits and bobs from the market - into a culinary patchwork creating a single dish. Charles Boutler adds further, “These dishes are very generous, yet they are sold for a penny each. The bucket costs three dollars. It contains everything from truffled chicken and game to beef and cabbage.” (Argoji, Dictionnaire d’Argot Classique)

• Peintre de pattes de dindons - Painter of turkey feet

A painter of turkey feet? This one quite surprised me. Actually, it made me gasp. Why would anyone paint turkey feet? And no, we are not talking about the Old Masters and their dark, moody still lifes of grapes, lemons, oysters, and the odd freshly-hunted carcass. Un peintre de pattes de dindons or painter of turkey feet was a tradesman who applied glossy varnish or dye to the legs and claws of turkeys, chicken, etc to make them appear fresh, thereby increasing their value. The limbs of a freshly killed turkey are dark and lustrous; as the days pass, they dull and pale, indicating the fading freshness of the bird. A butcher, hoping to pass off a several-days-old turkey as newly slaughtered, would hire one of these “painters” to restore the bright, glossy appearance. In the 19th century, this odd culinary trade was alive and well, still managing to deceive its customers. These professional “artists” were sought after by poultry sellers and butchers who depended on such tricks to fetch a better price for their tired, old birds.

Privat d’Anglemont gives a colorful description of one such tradesman at work: “It took a genius. Chapellier returned home and set to concoct a varnish that would preserve poultry legs with a brilliant sheen, even days after death, signaling their quality to gourmets… Two days later, triumphant, he returned to the market: ‘Eureka!’ he proclaimed. All the market women had been fooled themselves. The varnished poultry was tested—and passed muster with the finest cooks. For his painted fowl, Chapellier received half of the quarter that the sellers would have lost had they sold them with dull legs…”

In the November 25, 1848 issue of Le Corsaire, a professional painter of turkey feet - also referring to himself as a coloriste - explains his work : “When poultry isn't sold in time, what happens? The legs, once so black and shiny, go limp and turn pale! The color becomes dull and lacklustre, a telltale sign that drives buyers away forever. It is to me that we owe the varnishes used today by merchants to conceal the age of future roasts. Black varnishes, brown varnishes, pink, scarlet, and orange... the sublime art of the trade lies in knowing how to capture the subtle nuances of each type of leg, and to dress them according to their temperament.”

• Fabriquant de crêtes de coqs and Fabriquant d’os de jambonneau - Makers of rooster’s combs and ham hock bones

Two more unlikely professions that turned dishonest tricks into a trade were the fabricants de crêtes de coq - markers of faux cockscombs - and the fabricants d’os de jambonneau - someone who repurposed old ham hock bones for reuse - each an excellent example, along with our painter of turkey feet, of 19th-century food fraud practices. But each fascinating in its creativity and cunning.

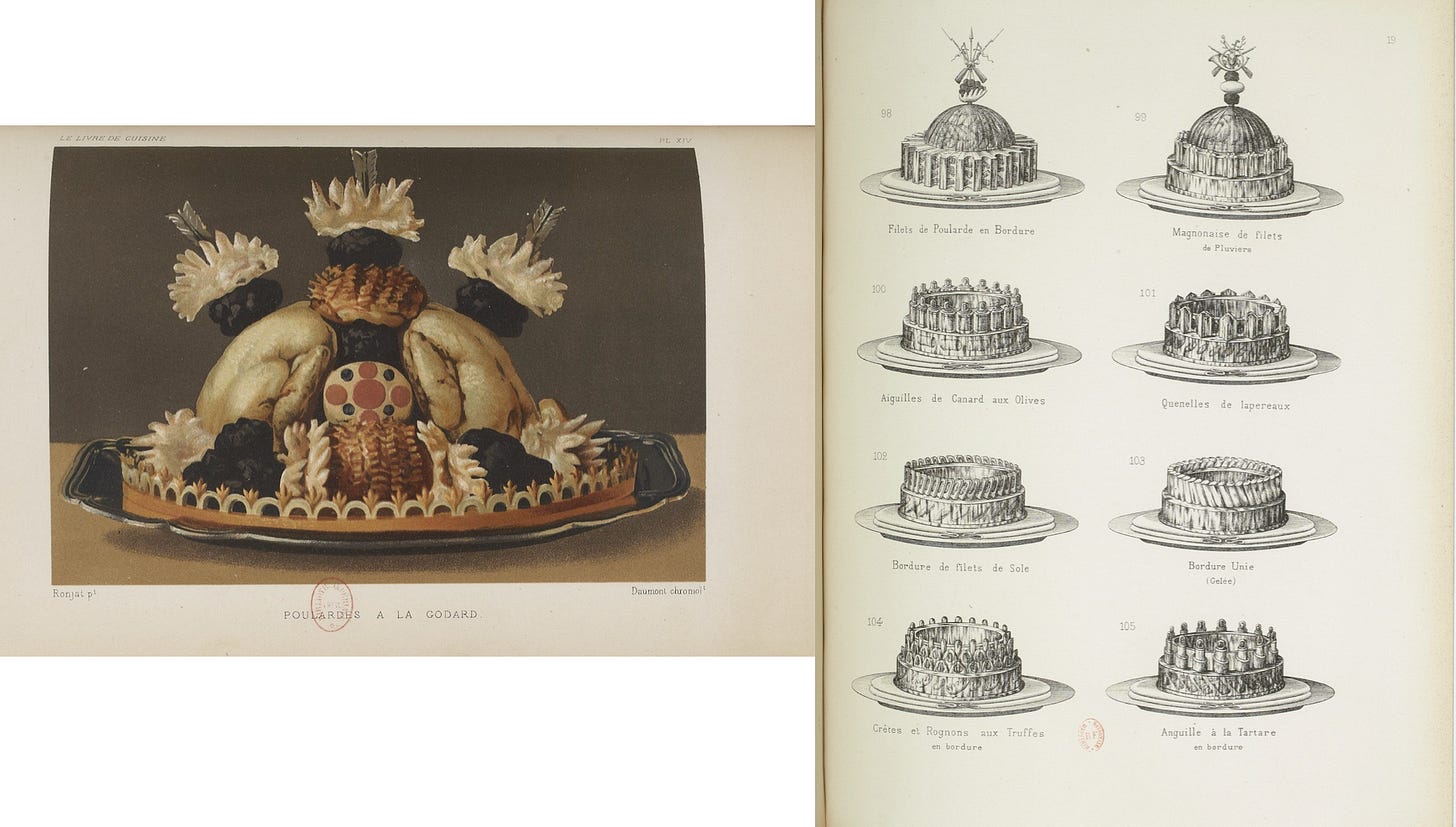

The first crafted rooster combs - quite a complicated and technical skill - from the palates of lamb, beef, or calves. Rooster combs - crêtes de coqs - were sophisticated delicacies, found in vols au vent or bouchées à la reine, combined in stews, served as a side dish with kidneys, or used as garnish on the most refined preparations. François Massialot offers a luxurious recipe for sweetbreads cooked with mushrooms, truffles, morels, cockscombs, and artichoke hearts in his 1691 cookbook Cuisinier Roïal et Bourgeois. The great Antonin Carême, in the first half of the 19th century, used cockscombs to garnish soups, all kinds of meat dishes, and tucked inside elegant aspics. But this delicacy was in such high demand with the upper crust and fine gourmets, it was said that “restaurants offered more stuffed combs than there were roosters slaughtered” thus creating a market for rooster comb “manufacturers”.

The second - the fabriquant d’os de jambonneau - reshaped and repurposed ham hock bones that would then be used to create new, fresh “jambonneau” or ham on the bone. The bones from old or used ham hocks (jambonneau) would be cleaned and combined with or wrapped in cheaper cuts of pork and fat and sold again as a new jambonneau or ham hocks, another way of making a seemingly high-quality product from leftovers while really keeping up the demand.

“We could do some clever statistical work here and prove that the number of ham hocks eaten in Paris exceeds by at least two-thirds the number of pigs consumed there. Before the advent of Mr. Oscar Mitbat, when people ate ham hocks in a workshop (workplace), they would leave the bone for a child to collect; the child would take it to the butcher, who would give him two pennies in exchange. So ham hocks are made; so this shoulder is a marvel of anatomy, a masterpiece that every good butcher must execute in order to be accepted as a journeyman in his art. In Paris, there are bones that have been in use for ten or twenty years, which leave the shop every morning covered in meat and return in the evening completely bare.”

• Le boulanger en vieux - Secondhand bread seller

Here is another seemingly innocent profession - turning stale bread into breadcrumbs and croutons - and yet, it was another cunning way for folks to earn money by reselling food recuperated off the tables (and plates) of others. The boulanger en vieux would collect uneaten, old, and stale bread from public schools, boarding schools, and seminaries - and most likely private homes and restaurants - and turn the stale crusts into breadcrumbs and croutons. “All of this comes from pieces that you left on the corner of your table two weeks ago. Fortunately, they say, fire purifies everything.”

The secondhand bread seller visited by M. Privat d’Anglemont had done very well by his business, as breadcrumbs and croutons were always in very high demand. He had several ovens going day and night to dry and toast the “mountains” of old pieces of bread, and “a multitude of laborers, men, women, and children who grated the hard bread as it came out of the ovens.”

“The charred parts,” the author explains, “are set aside and used to make charcoal for whitening teeth. This powder is then sifted through a silk sieve and sold to perfumers as tooth powder.

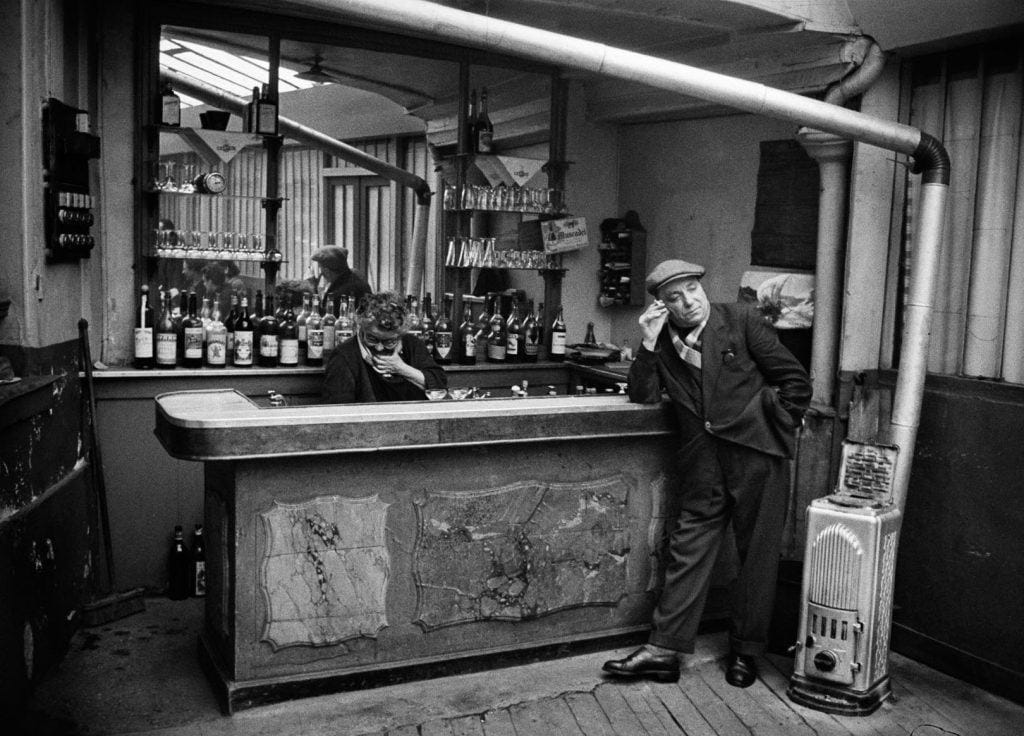

• L’ange gardien - Guardian angel

The guardian angel was employed by wine merchants and taverns, bistrots, or cabarets to watch over drunkards. According to Privat d’Anglemont, “he was charged with protecting them and seeing them home, answering only to the tavern owner who entrusted them to his care. He was obliged to defend them, put them to bed if necessary, and not leave them until they are safe, far from the reach of thieves known as les poivriers or “pepperers,” people without faith or belief who rob drunkards, showing no respect for the god Bacchus, whom they fervently worship…A good guardian angel must be sober; otherwise he would drink with his charge, and all would be lost.” One had to be qualified for this job as no other. “The angel must remain steadfast, impassive, not allowing himself to be led into temptation, going straight on his way, not yielding to any entreaty, not allowing himself to be intimidated by any threat. He must stand up to those who are drunk, always ready to throw himself into the fray when the customer indulges in his revelry on the shoulders of some long-suffering passerby.” And of course, like any good bodyguard, “in addition to all these moral qualities, he must also possess remarkable physical attributes. He must be agile, strong, and nimble, as he often has to carry his man on his shoulders to rescue him from the temptations and collisions that are so common at the barriers and in the market hall.”

• L’employé aux yeux de bouillon - The employee of broth eyes

The November 25, 1848 issue of Le Corsaire, the newspaper of entertainment, literature, arts, customs, and fashions, might be the first time this strange and …. distasteful job was mentioned in writing. L’employé aux yeux de bouillon - literally translated as the “employee of soup or broth eyes” was a hired worker who added grease or fat to plain, mediocre bowls of watery soup to give the appearance of a rich, meaty, alluring broth to increase its sales value. Les yeux - the eyes - were those lovely droplets or rings of fat/grease floating on the surface of a bowl of broth or soup normally left by meat; a bouillon aveugle - a blind broth - was a broth without “eyes”, without fat, usually in the case of an all-vegetable broth.

Bowls of broth or soup were often sold to customers in cabarets or clubs after a long night of carousing. To save money, the owner would make a cheap soup of old vegetables and vegetable trimmings or worse (one author wrote of ‘soup drawn from the fountain, and coloured with a bit of burnt onion’). He would then pay a meagre salary to his employé aux yeux de bouillon to do the rest: “The wretch would dip his fingers into a jar full of fish oil, then shake them over the bowls of broth lined up around the table. That's how he made eyes!” Or “Every morning, armed with this blessed syringe, I aim at the broths and execute, with a raised hand, a mosaic of eyes that would make nature pale in comparison.”

Or, as Privat d’Anglemont explained, tavern keepers would buy old second-or-third-hand meat bones from those regrattiers, who had no use for them, bones recuperated from restaurants or bourgeois kitchens. Those tavern keepers would “make a kind of hot water, which they color with carrots, burnt onions, caramel, and all sorts of ingredients….However, since these ingredients cannot provide what enthusiasts are looking for, namely broth eyes, a clever speculator invented the broth-eyed employee. Here is roughly how it is done: a man takes a spoonful of fish oil in his mouth at the usual time when customers are expected to arrive, and, pursing his lips and blowing hard, he releases a kind of mist which, falling into the pot, forms the eyes that so delight consumers. A skilled employee with broth eyes is a man who is highly sought after in establishments of this kind.”

So, fingers, a syringe or straw, or simply one’s mouth were the tools of the trade of this dubious little creature.

• La zesteuse - The zester

La zesteuse - the zester - referred to a woman who grated citrus zest for a living, primarily oranges and lemons. She would collect rinds from anyone in Paris who served or used lemons and oranges but normally discarded the outer peel: oyster sellers, limonadiers, restaurants, taverns, theatres, etc. The zest would be boxed up and sold to distilleries to extract the essential oils used in the production of eau-de-vie, curaçao; sirop de limon, orangeade, citronnade, limonade, essence de citron. This work was common in artisan distilleries in 19th-century Paris, particularly in working-class neighborhoods, but eventually this business grew. It’s said that distilleries all around France and around the world would purchase citrus zest from Parisian zesters. Privat d’Anglemont’s zesteuse was "a robust woman who, at the sight of an orange peel, would take up her knife and grate it with impressive speed. She could often be seen grating oranges in the streets or in makeshift workshops, contributing to the production of eau-de-vie.”

• Les loueurs de viande - Meat renters

Les loueurs de viande referred to butchers who rented out meat by the piece, rather than selling it outright, or renting out cuts of meat until needed for a client in his shop. These visually appealing, high-quality cuts of meat were rented to small restaurants or food sellers; the idea was that by displaying these beautiful cuts in their windows, even modest establishments could give the impression that their dishes were made with equally premium meat, while in reality they were cooking with cheaper, less impressive cuts.

"Fortunately, I added, the meat we see hanging in the windows of all these cheap restaurants looks good and tasty to me.”

“That meat is only there for show.”

“What do you mean, for show?”

“Yes, those cuts of beef, mutton, and veal hanging in the windows of the soup merchants don't belong to them: they're rented meat.”

“Rented meat! From whom, and why?”

"To serve as a display, to attract customers to the shop. These people sell a plate of meat for six sols at most, three sols at least; they can therefore only use low-quality meat. And what do you see in their shops? Magnificent fillets, superb legs of lamb, succulent entrecôte steaks. If they gave that to their customers, they would go bankrupt. So they make deals with butchers who, for a fee, agree to rent them whole animals, sometimes even. The renter takes them back when he needs them.

“That's another industry I didn't know about. I had no idea that meat was rented out.”

(From Paris Anecdote by Alexandre Privat d’Anglemont, 1854)

Thank you for reading and subscribing to my Substack Life’s a Feast. Please leave a comment, like and share the post…these are all simple ways you can support my writing and help build this very cool community. If you would like to further support my work and recipes, please consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Thank you - this article is such a GIFT! I just finished reading Zola's Ventre du Paris which takes place in Les Halles at the exact same time period. I was totally surprised to read about food resellers in Zola, and it is amazing to see the service reappearing in your article.

You’re right, this was a gem, with amazing photos of the bustling life in Paris them! Thanks for posting. 🥖🥐🦪