Gentle reader, try it, it's delicious, your husband will be delighted. - Raymond Herment, Au Royaume de la Fée Diane d’Esterel, 1952

"The pissaladière merchant rides his bicycle, balancing his huge onion tarts on his head. Through the streets of the old town he goes, carrying the precious manna and supplying the stores as and when they need him. He's a considerable character who knows the latest news long before journalists do, and doesn't mind spreading it around. His breath is fragrant.”

Today we head south to discover another popular traditional dish from the region of Nice. La cuisine niçoise is a Mediterranean cuisine rich in tomatoes, eggplant, onions, garlic, fish from the sea, and, of course, olives and olive oil. I’ve already introduced you to la salade niçoise and pan bagnat, and the ratatouille niçoise - with la bohémienne, a dish from Provence - and, of course, the beautiful tian, each a mighty fine summer dish filled with the season’s freshest garden vegetables.

Our little pissaladière merchant on his bicycle zipping around the old town of Nice, so wonderfully described in Le Petit Journal in August 1932 as one of the central figures of authority (authority as in one who can be counted on for all the latest news and gossip), introduces us to today’s dish, la pissaladière. The 15 January 1935 issue of Les Cahiers de Radio-Paris describes this treat as “a wonderful tart whose contents are a mixture of lots of onions, a little anchovies, and a few black olives.”

It’s thought that earliest versions of the dish likely date back only to the 18th or the first decades of the 19th century, but we do know that by the early 20th century, pissaladière - or pissaladiera in local dialect - had become a defining feature of street food culture in Nice, and more widely throughout Provence, sold not only in bakeries but also by street vendors, particularly in Vieux-Nice, the old part of the city. The street vendor, le marchand de pissaladière, as the above quote highlights, became a well known and symbolic figure, weaving through the city as a distributor of food, news, and gossip.

In 1946, Benoît Mascarelli captured this atmosphere in La Table de Provence & Sur la Côte d’Azur, offering a vivid portrait of the pissaladière vendors—by then a veritable institution in the streets of old Nice and a fixture of everyday life.

“All the alleys of old Nice are scented with the sweet emanations of pissaladière....you'll find young men and old women balancing on their heads very large tin containers whose indiscreet lids let out a delicious smell of cooked onions. All these carriers come from “bakeries” specialized in cooking pissaladiera, and they go to sell it at the market where, for a few coins, you can truly feast.”

It is disputed exactly how and when the pissaladière made its way from the Liguria region of Italy, from whence it originated, up to the south of France and into niçoise kitchens. Nice was long connected to the Ligurian region by culture, language, and politics; Nice was Italian-speaking and Ligurian-influenced well into the 19th century and only officially became French when it was ceded to France in 1860 as part of a deal between Napoleon III and King Victor Emmanuel II of Sardinia-Piedmont during Italy's unification.

Ligurian cuisine influenced the region of Nice for centuries, The name "pissaladière" comes from the Niçard (Occitan) word "pissalat", which derives from the Ligurian dialect "peis salat" meaning salted fish paste, a product used in ancient Mediterranean cuisines; the Roman fermented fish sauce garum is noted as far back as the 1st century. Pissalat niçois is a fermented anchovy paste used as a condiment, a topping, or a base flavor in many niçois dishes, including la pissaladière. This way of preserving fish, particularly anchovies, by salting or fermenting it and preserving it as a paste was common along the Mediterranean coast down to Liguria where preserving fish was a practical necessity. Louis Roubaudi described pissalat in his 1843 book Nice et ses environs as “very suitable to awaken the appetite.” Which, of course, it does, sharp and salty.

It is believed that the pissaladière was inspired by the traditional Ligurian flatbread which was commonly topped with anchovies or sardines, garlic, olives, and sometimes tomatoes. Once it found its way to Nice, the locals added onions in abundance.

“But the Niçoise cuisine I want to tell you about,” wrote Dr. Louis Camou in the Provence issue of France à Table in 1935, “is not the kind you'll find in palaces, hotels, and restaurants. We're talking here about the special dishes served on the tables of all the old families of the country, on the menus of regional meals, and which you'll eat every day in some of the most popular restaurants.”

Pissaladière was—and remains—not just a popular street food, but also a rustic, home-style dish, typically prepared in family kitchens or served in modest neighborhood eateries. As such, when searching for recorded recipes, it tends to appear only in family-oriented cookbooks featuring home-style fare, in regional collections that highlight local specialties, or in cookbooks dedicated specifically to the cuisine of Provence.

There are some outsiders who take a sort of malicious pleasure in criticizing this tasty dish, which in our opinion is one of the treasures of Nice cuisine. - Benoit Mascarelii

La Pissaladière is a delicious tart that makes a fabulous cocktail finger food, is great for picnics or brunches, a starter, or a main course for a light meal with a salad. It’s best eaten hot, but is still excellent eaten warm or a room temperature.

La Pissaladière traditionally allows you to adjust the recipe to make it as you love best, whether you add tomatoes or not and how you include the anchovies:

Traditionally, there are 3 different ways one can incorporate the anchovies into the pissaladière: make an anchovy butter, as I did, and spread it on the dough before covering with the cooked onions; about 5 or 10 minutes before the end of cooking, stir the anchovies into the cooking onions, stirring until the anchovy filets melt into the onions; Simply lay the anchovy filets in a pattern on top of the onions and then dot with the olives.

Tomatoes, while being an important element of la cuisine niçoise, are optional, and not often seen in recipes. If you choose to include them in the recipe, you can either: chop up 2 or 3 ripe tomatoes and sautée them in a little oil or butter, salt, pepper, and herbs, fresh or dried, until they are reduced to a thick purée or sauce with not an iota of watery liquid in the pan - this is then layered with the onions; or slice a couple of ripe tomatoes and lay them on top of the onions before dotting with the olives and baking.

Pissaladière

Preheat the oven to 400°F (200°C). You will need a 10 x 15 - inch (25 x 38 - cm) jelly roll pan (a rectangular baking pan with a lip all around). Lightly oil the pan, bottom and sides.

Pâte à pain - Bread dough (recipe follows)

4 tablespoons olive oil

2.2 pounds (1 kilo) yellow onions, trimmed, peeled, and largely diced

2 large-ish cloves garlic, peeled and just mashed

¼ teaspoon salt

½ teaspoon dried thyme, more for dusting

Freshly ground black pepper

1 can - 3.5 ounces (100 grams) anchovy filets with oil; 2.5 ounces (70 grams) anchovies drained - or slightly more; oil reserved

3 - 4 tablespoons (50 grams) unsalted butter, softened

12 or so black olives, preferably salty niçoise or Greek olives, pitted if possible

Pâte à pain - Bread dough for pissaladière

2 cups (280 grams) flour for the dough + 1/2 cup (70 grams) for kneading and rolling

1 teaspoon active dried yeast

1 teaspoon salt

¾ cup (175 ml) tepid water

3 tablespoons olive oil

Prepare the bread dough for the crust:

Have either a baking sheet or large mixing bowl ready with about 1 tablespoon of olive oil in the center/bottom on/in which the dough will rise.

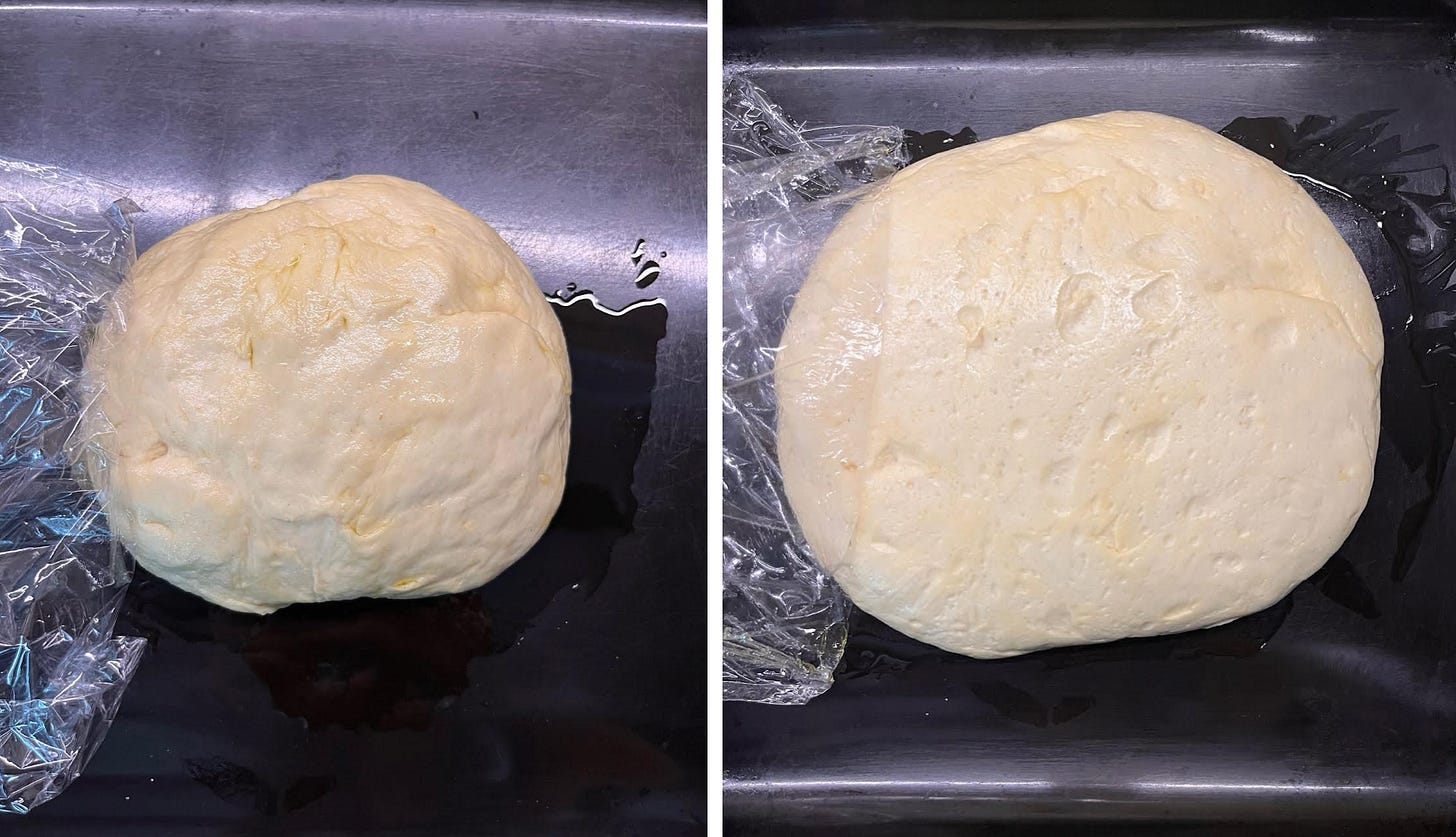

Place the 2 cups (280 grams) flour in a medium or large mixing bowl; make a slight well in the center. Add the dried yeast, the salt, water, and olive oil. Using a wooden spoon, stir well until all of the flour is damp and incorporated into the scraggily dough and all of the ingredients are well blended/dispersed. Scrape out onto a floured work surface (using the extra flour) and knead, adding flour a little at a time as you knead, until the dough is no longer sticky and is soft, smooth, and elastic; this should take about 5 minutes. Gather the dough into a ball and place either in the bowl or on the baking sheet; roll the dough to evenly and lightly coat it all with olive oil. Cover with plastic wrap (or a clean kitchen cloth) and let rest and rise at room temperature for 2 hours - while you prepare the filling. It should about double in volume.

Prepare the filling (onions and anchovy butter):

Place the 4 tablespoons olive oil in a large sauté pan, skillet, or deep heavy pot and heat over medium heat. Add the onions and mashed garlic cloves and stir so everything is coated with oil.

Stir in the salt, the dried thyme, and several grindings of black pepper. Once the onions start sizzling, lower the heat to medium-low - you want to cook the onions slowly but still hear the sizzling during the whole cooking time - 40 minutes. I lower the heat a bit more and cover the pot for the first 20 minutes, lifting the lid and stirring occasionally. After the first 20 minutes, remove the lid, raise the heat under the pan just slightly, and continue to cook, stirring often, for an additional 20 minutes.

You do not want the onions to brown, caramelize, or - most importantly, burn - so if they begin to stick (they might towards the end of cooking), lower the heat a bit and stir more often.

After about 30 or 35 minutes of total cooking time, stir in a couple tablespoons of the reserved oil from the anchovies. Taste the onions and add more salt and pepper if you think it needs it.

Near the end of cooking, the onions should become a slightly deeper yellow color and become almost creamy.

At the end of the 40 minutes, turn off the heat under the onions and let cool a bit while you roll out the dough and line the pan.

While the onions are cooking, open the can of anchovies and drain the oil out into a cup or small bowl and reserve for the onions. Lift out the anchovies one at a time and, if whole, carefully slide a knife down the center to separate the 2 filets, then lift/scrape out the center bones and discard (the bones). If the anchovies are really salty, you can rinse them under cold water to lessen the saltiness before puréeing them. Place the cleaned anchovies in a bowl with the softened butter and, using a fork, turn it into a smooth paste. Set aside.

Place the risen dough on a clean work surface dusted with some of the reserved flour and dust the dough with a little more; lightly knead the dough to deflate then roll out the dough into a rectangle the size of the jelly roll pan, flouring both the work surface under the dough and the dough itself, as needed to keep the dough from sticking to the surface and the rolling pin to the dough.

Carefully and lightly roll the rectangle of dough around the rolling pin, lift it up and transfer to to the lightly oiled jelly roll pan and unroll. Place the rectangle well in the pan and carefully stretch and press the dough to fill the corners and up the sides to the rim. The dough is beautifully soft and pliable. Prick the dough with a fork.

Scrape the anchovy butter onto the tart dough and using a flat blade - I used a long offset spatula - or back of a large spoon, carefully spread the butter across and evenly over the dough all the way to the edges and into the corners.

Scrape the cooked onions onto the anchovy butter and, again, carefully, gently spread the onions evenly across the tart to the edges and corners.

Evenly space out the olives across the surface.

Bake in the preheated oven for about 30 pr 35 minutes until the onions are golden and beginning to look caramelized and the bread dough is baked and golden. (I cooked mine for 40 minutes and, while really good, the dough was a bit crispier than I would have liked it)

Remove from the oven and serve.

Thank you for reading and subscribing to my Substack Life’s a Feast. Please leave a comment, like and share the post…these are all simple ways you can support my writing and help build this very cool community. If you would like to further support my work and recipes, please consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Absolutely love your recipes but placing them in their cultural and historical context make them extra special!

I love the idea of anchovy butter! I was taught in Arles at a tiny cooking school to melt anchovies in olive oil with a couple of cloves of chopped garlic to make the base under the onions. I am enamored of the sweet/salt flavor, and make this several times a year!