The potato, the vegetable of the hut and the castle. — Louis De Cussy

“Ah, Monsieur!”

“Well, my good man? What is it?”

“Why, you’ve been robbed! Yesterday, at nightfall, when the soldiers of the guard had left, the people of the plain came to plunder your potatoes!”

“Did they take a lot?”

“Oh yes, sir! This is a disaster! All the fields by the river have been dug up, turned over; you won't get more than enough to fill your hat now! And if you don't have the rest guarded both day and night…”

But the gentleman was no longer listening. “It's going well! Oh, they'll have to come!” Then taking his cane and his hat, he strode away with a jaunty step, his face radiant, and immediately ordered a grand diner. Was he crazy? No! He had just conquered a prejudice!

(From Parmentier et la Pomme de Terre by Charles Delon, 1882)

Our story of a clever Parmentier who, in order to stir up both curiosity and talk, had those fields of potatoes outside of Paris heavily guarded by soldiers all day long, and yet…come nightfall, the soldiers were ordered - by Parmentier himself - to quit the grounds, leaving the fields of potatoes open to pillaging and looting. His idea had been to create enough unbridled interest in those potatoes during the day, making the population believe they were so precious as to require guarding by the King’s soldiers, as to make people want…. DESIRE…those tubers! He purposefully left the fields unguarded at night, hoping the people WOULD come and steal them, cook them, eat them, and, realizing how good they were, want more.

“Potatoes, as a dish, disguise themselves in a thousand different ways, and lose the wild taste they're accused of in different ways. These roots are used to make doughnuts, cakes, and tarts that are so similar to almond tarts, they're sure to impress even the most discerning connoisseurs.” Antoine Augustin Parmentier, Examen Chymique des Pommes de Terre 1773

As we saw in the previous post, Antoine Augustin Parmentier and his scientific colleagues spent many years studying the culinary and nutritional attributes of the humble potato and trying to convince the general population in France - often the last to accept a new fruit or vegetable, suspicious of possible poisonous qualities or simply thinking them purely ornamental - to give it a try. Only thanks to a series of wheat shortages and “little” famines, along with the help of Louis XVI, did Parmentier succeed.

The potato finally begins making its appearance in cookbooks. After a single, short mention in Nicolas de Bonnefons’ Les Délices de la Compagne in 1654, the French must wait until 1796 when François Cointeraux writes La Cuisine Renversée ou Le Nouveau Ménage (The Reversed/Upended Kitchen or The New Household).

Cointeraux was a professor of rural architecture; curiously, he invented the crécise, a mechanical device for producing adobe bricks, from which he developed a kitchen version, a tool that would allow a cook to dry vegetables. And for some reason he decided to write a book about the potato. He claims to have written his book to counterbalance the old cookbooks, cookbooks with titles like Le Cuisinier Bourgeois or La Cuisinière Bourgeoise, written for upper middle class households with money and little need to or thought of economy, especially in the kitchen. But he knew full well that these books’ recommendations for household economy were outdated, not appropriate or adapted to the day or to modern pocketbooks. He knew that the potato was one answer, a foodstuff delicious, nutritious, and cheap, and one that could be adapted to so many ways of cooking it. “It's true that we've added a few ways of preparing potatoes to these old and ancient recipes, but they're not enough to make the most of this valuable resource, as we'll soon find out.”

He begins by complaining that someone somewhere decided to call both the apple and the potato pomme, “There remains the problem of distinguishing the pomme fruit from the pomme hortolage. It would still be appropriate to call the fruit apple (pomme fruit) a seeded apple, and the other apple (pomme) a potato (pomme de terre) or seedless apple.” - I will interject that when one currently sees pommes frites on a restaurant menu, one knows that it refers to fried potatoes, not apples.

While annoyed by the name, Cointeraux does really love the root vegetable: “Never has a foodstuff been more useful, and this one is arguably the most essential. Indeed, turnips, cardoons, artichokes, carrots, cabbage, asparagus, pumpkins, and other vegetables are, without a doubt useful in households, but they are far from being as useful as the potato. Abundant harvests are easy to obtain and, as a result it’s an inexpensive foodstuff, which is the basis for much-needed savings in every household. Everyone knows several ways to use the potato, but don’t know the quantity of new dishes they can provide. Even the most experienced housekeeper will be astonished by this.” He then lists the many ways his own family cooks and enjoys the potato: in soups, fricassees, stews or fried; they can be used to make pâtés, tourtes and tarts, custards, noodles, macarons, purées. They are used to accompany roasts or in sauces. They can even be dried to be eaten in the summer months. He continues by boasting of all the delicious pastries that can be made using potato flour. This “new household”, finding itself in the middle of a Revolution, less rich, more economy-oriented, found an excellent resource in the potato. The potato was no longer presented as either a replacement for cereals or only as poor man’s sustenance, but as a real accompaniment to a dish or as a main course, and the starch finding so many uses in pastry.

By the time André Viard wrote Le Cuisinier Impérial in 1806, the potato was already abundantly used and in recipes still popular today. Not only boiled, baked, stewed, and sautéed, potatoes are now used a binder, ground together and blended with chicken, egg yolks, heavy cream, nutmeg and pepper, shaped into balls or quenelles that are poached in broth then served with the soup, or as meat stuffings for pies and poultry. Viard also slices potatoes, boils them in broth with chopped fennel and, again, served in a bowl with the broth, using the potato in the place of the usual slices of bread or croutons. He, as will shortly become common, recommends serving potatoes with meat dishes, and potatoes are now steamed, boiled, or sautéed in butter, and cooked and served in cream or lemon sauce, with loads of fresh herbs, or they are puréed or mashed. And now potato starch goes beyond bread and sea biscuits, used to make both cakes and soufflés.

In 1836, M. Burnet pens the Dictionnaire de Cuisine et d’Économie and writes of the potato “We distinguish 11 garden varieties; each of the 11 varieties can be used indifferently for all uses (in cooking)”, although he names 4 specific varieties that “have more delicate flesh” which are most appropriately “destined for the table.” He then gives several pages of recipes and ways to prepare them, including stews (haricot) and ragouts, salads, quenelles, a potato cake, and frites.

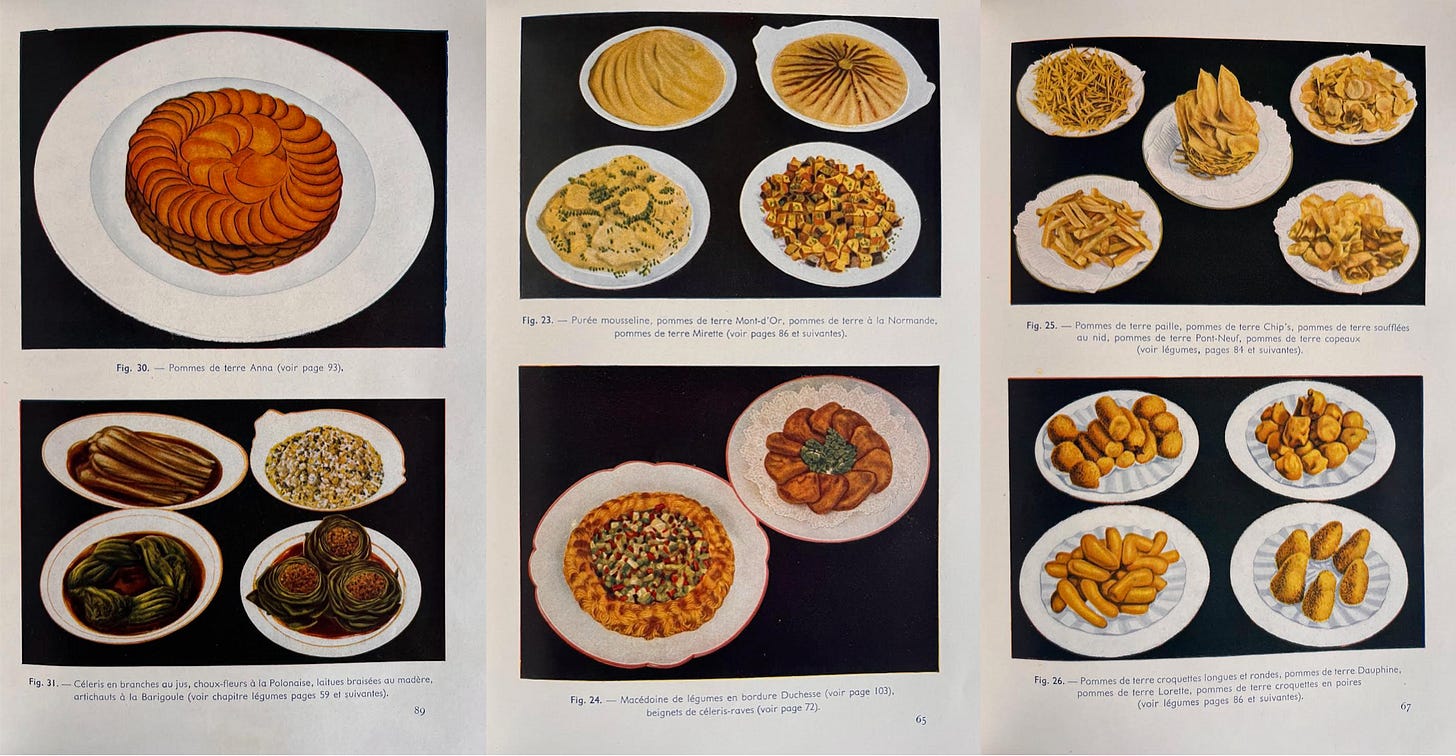

Not only are recipes filling the pages of cookbooks, but they have become a fairly common side dish in Parisian restaurants, from à la Lyonnaise, sauté au beurre, à la maître d’hôtel, croquettes or frites, even charlotte de pommes de terre. And by the first half of the 20th century, the potato has truly become a staple of French cuisine, in both restaurant and home cooking.

To repeat Victor Forbin’s astute observation “I'd be remiss if I didn't mention the thousand and one ways in which our fine French chefs accommodate these precious tubers. And it's worth noting that everywhere else, potatoes are eaten in only two forms: boiled in water or mashed.” The potato, despite all former disdain, the years of debate on its usefulness, and its long, long wait to be embraced by the French, has become so very French, indeed. The French quickly applied their culinary ingenuity to refine the potato, creating dishes worthy of the grandest tables in the land, delectable for the humblest peasant, laborer, and middle class family. Leave the boiled and mashed potatoes to those less creative cultures…

By the turn of the 20th century, the potato had become a popular staple in the French kitchens, recipes flooding cookbooks, from soups and salads, potatoes fried, stuffed, cooked in butter or broth, in wine or with cheese , turned into quenelles and croquettes, beignets and gratins. By 1928, Austin de Croze listed 13 potato dishes in his cookbook of regional cooking, that, 135 years after the French began eating the potato, lifting it up into a culinary ingredient, that were already considered traditional dishes of various regions in France.

But…

…while knowing that the potato itself, boiled, fried, fricasseed, puréed, was an excellent foodstuff, Parmentier’s passion lay in drawing out the starch from the potato, an easy process, he claimed, and drying it into a powder that could be used to make bread as a substitute for wheat flour. This work was carried out simultaneously and since by both scientists and chefs, and it quickly became a much-used ingredient in the French kitchen.

We saw how Antonin Carême, one of France’s most influential, most innovative chefs in the nation’s history, a genius, many believed him to be, embraced potato starch dramatically, using it to lighten cakes, cookies, and pastries in abundance; he is thought to be the first to have substituted potato starch for some of the flour in the gâteau de Savoie to lighten it even more than it was. But he might not have been the first to experiment with it. In the 10 May, 1783 issue of the Gazette du Commerce, an article was written on the Potato cookies from Sieur Courtois, master confectioner, rue Croix-des-Petits-Champs, vis-à-vis the small passage S. Honoré, near the barrière des Sergens, Paris: “The use and advantages of the potato are now well known. We know it is an easily digestible food and is well-suited, for this reason, for delicate stomachs. We prepare this root in a variety of ways. But before sieur Courtois, no one had thought to make cookies (biscuits) only using potato starch. He began doing this 18 months ago. These cookies are all the more deserving of the public’s confidence…the potato starch is prepared with the greatest care; the cookies remain fresh for a long time; they contain no almonds (almond flour or ground almonds were a common ingredient in pastry) which are bad/unsuitable for many stomachs. These cookies can be different shapes and sizes, as large as a biscuit de Savoie, as small as ladyfingers, or round like the most common cookies. M. Courtois makes pastries with using potato starch for those who order them. These pastries are lighter and more agreeable than those made with wheat flour. One can also purchase potato starch at his shop for a reasonable price.”

By 1821, according to Archambault in Le Cuisinier Économe, potato starch of very good quality could easily be purchased at all grain merchants’ establishments. He uses it specifically to make donuts and soufflé’s. In 1877, M. De Montot urges the production of potato starch and its distribution in packets to be used in jellies, broth, porridge for children, and in creams in his pamphlet Observations Très-Importantes à l'Humanité, sur l'Amidon de Santé (Observations of Great Importance to Mankind, on Healthy Starch). M. Buc’hoz, author of L'Art de Préparer les Alimens, Suivant les Différens Peuples de la Terre (The Art of Preparing Food, According to the Different Peoples of the World) states: “For several years now, we have widely recommended the potato as a foodstuff. One can use them to make cakes and bread (using the pulp - purée - or reducing the potato to starch or flour).” He includes a lovely recipe for crème de pomme de terre or potato custard which is thickened with potato starch, sweetened, and flavored with orange flower water and lemon zest which, he says, can also serve it with a caramel sauce.

The authors of Les Classiques de la Table, 1845, “Publiés à Paris pour la Gastronomie et la Vie Élégante” (published in Paris for gourmet dining and elegant life), explain “Starch nourishes perfectly, and all the more so as it is less mixed with foreign principles. By starch we mean the flour or dust that can be obtained from cereal seeds, legumes, and several root species, among which the potato ranks first. Starch is the basis of bread, pastries and purées of all kinds, and thus makes up a very large part of the diet of almost all peoples.” Both Jules Gouffé and Gustave Garlin are indeed using potato starch for all kinds of pastries in their cookbooks Le livre de pâtisserie of 1873 (Gouffé) and Le Pâtissier Moderne in 1889 (Garlin), using it to make soufflés, every kind of cake, most particularly the génoise or sponge, and biscuits, or small cookies. Their pastry books are simply dotted with this now popular baking ingredient.

And from there, there is no stopping the French. Cookbooks and women’s magazines are filled with the potato which has now become a household kitchen fixture in France.

“A scorned and despised tuber, (Parmentier) made it one of the most precious and widely used foods at the table of the poor as well as the rich.” Ernest Laut

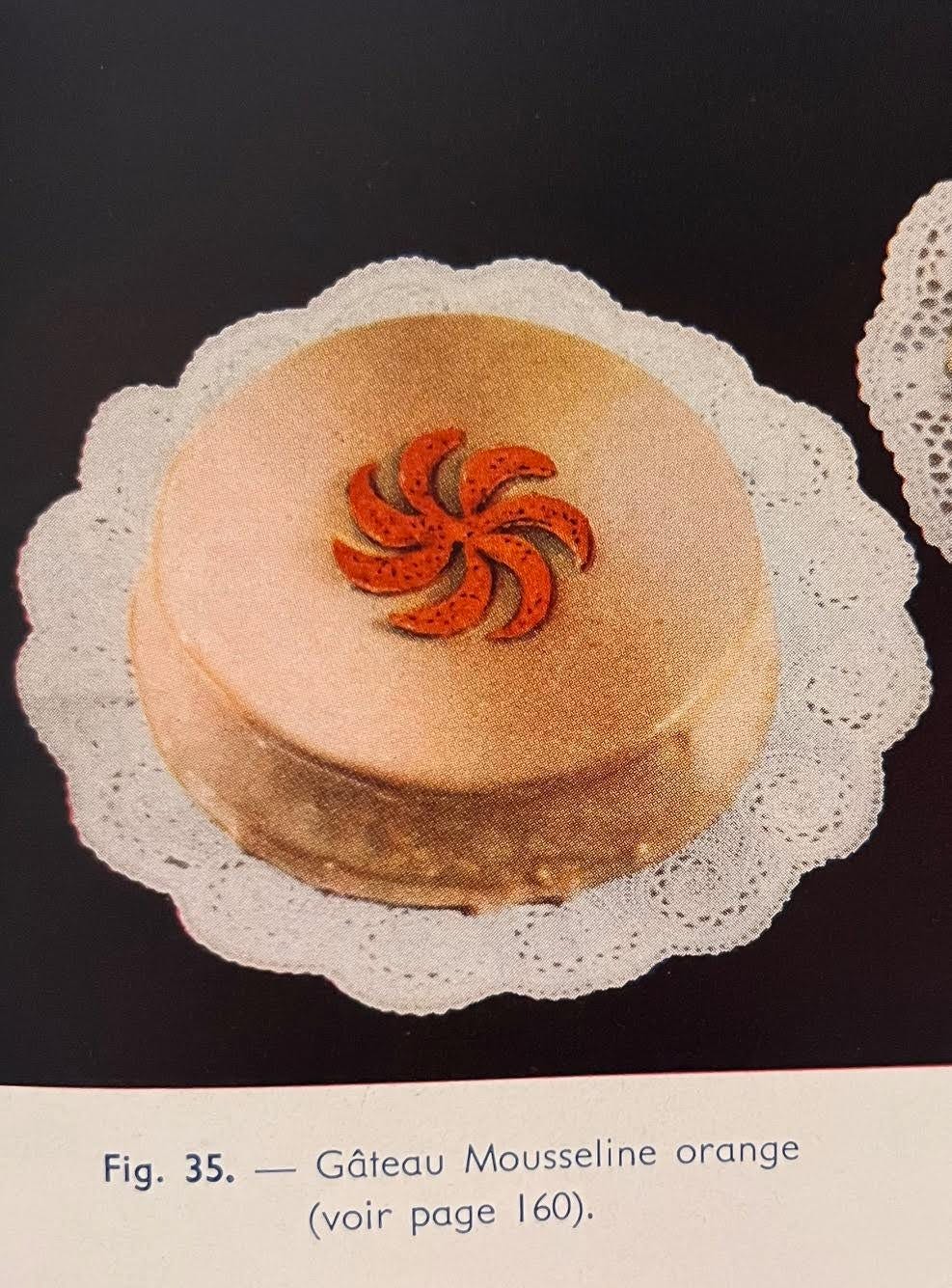

Orange Mousseline Cake

This is a recipe from Henri-Paul Pellaprat’s 1937 Cuisine Végétarienne, his gâteau mousseline à l’orange (image above from the cookbook). While potato starch, which replaces some of the regular flour, makes for a light cake, it also adds a dense toothsomeness, making for a very slightly chewy, really satisfying cake. The simple orange icing intensifies the delicate orange of the cake.

4 eggs, separated - using 4 yolks and only 3 whites for the cake

1 cup + 2 tablespoons (125 grams) granulated sugar

¼ cup + 2 tablespoons (50 grams) regular all-purpose flour (*see note)

¼ cup + 1 tablespoon (50 grams) potato starch (fécule de pomme de terre) (*see note)

Finely grated zest of 1 orange

Orange icing

1 cup (110 grams) powdered/icing sugar, more if needed (*see note)

2 tablespoons freshly-squeezed orange juice, more if needed

* note: to measure the flour, the potato starch, and the powdered/icing sugar, stir up the dry ingredient to lighten, then lightly spoon into the measuring cup or tablespoon until slightly mounded over the rim/edge. Using a flat blade, level the top. Have a sieve or fine-meshed strainer ready to sift the flour and the starch together onto the batter.

Preheat the oven to 325°F (160°C). Butter the bottom and side of a 9-inch round x 2-inch deep cake pan (I used a nonstick which was wonderful) - 23-cm round x 5-cm deep. - If your pan is does not have a nonstick surface, don’t hesitate to line the bottom of the buttered cake pan with a round of parchment.

Separate the eggs, placing ONLY 3 eggs whites in a medium-sized mixing bowl, preferably plastic or stainless (I always beat whites in a plastic bowl), and the 4 yolks in a medium-to-large mixing bowl. Place the unused egg white in a small, covered container in the refrigerator for another use. Whites can stay in the refrigerator for several weeks and are better for beating whites as they age.

Add the orange zest to the sugar. Place the flour and the potato starch in the same small bowl.

Add a very small pinch of salt and, if you have one on hand, just 2 or 3 drops lemon juice into the egg whites. Using very clean beaters, beat the whites on low speed for 30 seconds then gradually increase the mixer’s speed to high; continue beating on high until the whites are thick, opaque white, and peaks hold when the beaters are lifted out. Touch the whites and they should be dense. Tap off the excess whites clinging to the beaters.

No need to wash the beaters if you’ve tapped off the excess whites. Now beat the 4 egg yolks on high for a minute until they are creamy; Gradually beat in the orange zest and the sugar as you continue to beat on high speed (I add the sugar gradually only to avoid splattering). Continue to beat for a couple of minutes until this batter has doubled in volume and is thick, pale, and creamy.

Now fold in the beaten egg whites and the flour/starch, alternating the two and adding the whites in 3 additions and the dry ingredients in 2 - sifting the flour/starch onto the surface of the batter with both additions. Once the dry ingredients and the last of the whites have been folded in, make sure the sides have been well scraped down, the bottom of the bowl well scraped, and the batter is well blended. You do NOT want to overwork the batter or you will deflate the whites, but you do not want anymore dry ingredients or lumps of whites visible.

Pour the batter into the prepared cake pan; give it just a quick back and forth jiggle to (mostly) level the top, then bake in the preheated oven for about 1 hour. The cake will puff up then sink slightly at the end of baking, the cake will be a nice deep golden brown and the sides will have begun the pull away from the pan.

Place on a cooling rack and immediately but carefully run a knife blade around the sides to loosen the cake from the pan. Let the cake cool for several minutes in the pan before turning it out onto a cooling rack - leave the cake inverted/upside down - and leave to cool completely before transferring to a serving platter and icing.

To make the icing, sift the powdered sugar into a bowl, add the 2 tablespoons orange juice and whisk until perfectly smooth. Add a bit more potato starch (I added 1 more tablespoon) if the glaze seems to thin. Whisk occasionally for several minutes to allow it to begin to thicken just a bit, then pour onto the cooled cake. Using a large offset spatula (or equivalent) carefully spread the icing all the way to the edges. As the icing sits it will begin to set; I spread the icing evenly across the cake and to the edges - letting some drip down the sides - as it was setting.

Allow the icing to set completely, forming a thin, crisp “crust” on the cake.

Thank you for reading and subscribing to Life’s a Feast by Jamie Schler. Please leave a comment, like and share the post…these are all simple ways you can support my writing and help build this very cool community. Let me know you are here and what you think. You are so very appreciated.

I blocked that nasty user....

Having run a few potato disease and pest research programs, I've always been fascinated by the history, both good and bad, of the fabulous tuber. I had previously read about Parmentier's ploy to gain acceptance for the potato, but never as well presented as it is here. A really fun read on a day when fun is a little hard to come by.

Thank you Jamie.

BTW. I too have now blocked RRL 🚫. Not worth the space on my timeline.