In the creation of a dessert, we find the purest expression of culinary elegance. - Auguste Escoffier

“And now, the truth about Peach Melba — straight from Mme Melba herself, and we know the worth of every word that leaves such lips….”

The “truth” about pêche Melba is charmingly told by Pierre Maudru in the pages of the cultural daily Comoedia. “Mme Melba was scheduled to sing in London at a charity concert. Around 4 o’clock in the afternoon, she asked her hotel — The Savoy — if they could prepare a peach for her. The chef at the Savoy was the famous (Auguste) Escoffier. Wishing to distinguish himself in the eyes of the great artist, his genius led him to invent a new preparation. “Oh! This is delicious!” said Mme Melba upon tasting it. “Quick, ask the chef what he calls this kind of peach.” Escoffier replied that it had no name, but since it had had the honor of pleasing Mme Melba, he asked for permission to name it after her. As you can see, the story is quite simple. Simplicity — that is what characterizes this extraordinary artist.”

But nothing is quite as simple as it is told in the pages of a newspaper.

The birth of a dish is often shrouded in legend, and more often than not, several conflicting legends; it's rare for us to know the precise circumstances of its creation or the name of its inventor, or of those who participated in its evolution. So one might assume that the creation of the Pêche Melba would be straightforward — a relatively recent invention, surely well documented. And yet, the story, like so many others, begins to shift and blur the moment we try to pin it down—even in Escoffier’s own telling.

Maudru met Madame Nellie Melba, the Australian opera singer, in 1926, some thirty-five years after Escoffier named his now-iconic dessert after the celebrated soprano, in the early years of the 1890s. In the space of three decades or so, facts shift or soften, memories become fuzzy around the edges, or made to fit someone’s desired folklore. Maudru “wanted her to tell us about her life. And before the time for speeches came, there was nothing but anecdotes and pleasant chatter, perfecting the legends, particularly the controversial one about the famous ‘Peach Melba’.” And the star regaled Maudru with her simple story.

In 1925, just six months earlier, a journalist for La Toque Blanche, a weekly trade publication for chefs, had visited the great Escoffier himself in his London lodgings to ask him about the origins of this famous dessert.

“The Peach Melba?” he repeated (when asked), a little surprised, “It was some years ago and really, I've forgotten the whole affair.” - “You've forgotten preparing dessert in honor of Mrs. Melba, after hearing her sing at Covent Garden?” - “I don't believe I ever heard Mrs. Melba sing...” - “Then the story that you invented Peach Melba isn't true?” - “I don't think so,” he replied with an amused smile.”

Escoffier went on to say that he remembered Nellie Melba being a guest at the Carlton Hotel 25 years earlier, and he, Escoffier, was in the habit of preparing special dishes for her. He remembers that she adored peaches and ice cream topped with Cardinal sauce and Escoffier served it to her and her friends often. They requested this dessert so often, he was obliged to add it to the menu. “Since it was her favorite dessert, I named it after her.”

“It’s truly regrettable that the history of your inventing this dessert isn’t true,” the journalist said, sadly. “I won't contradict it if you wish to publish it,” replied M. Escoffier, laughing, “Who said history is anything but a lie we agree on?” The journalist dutifully recorded Escoffier’s words — much to his own chagrin — ending with a regretful sigh: “but at the same time destroying one of the finest culinary legends of our time.”

So, was this simply a case of he-said-she-said? For one of the culinary world’s most iconic desserts?

As it happens, Madame Melba herself would weigh in, flatly contradicting that very account. In Melodies and Memories, her memoirs published in 1926, she devotes a single page to the event that would come to define her name in kitchens around the world. With characteristic fire, she wrote:

“I have told this story in full because I am always receiving messages from chefs in hotels all over the world, that they were the originators of Pêche Melba. Whether they think that my memory is particularly short, or whether they imagine I am merely a fool, I don’t know, but I have had quite fierce arguments about it. Only the other day, in Paris, Escoffier came to me in great concern saying that some American journalist had published a story in which he (Escoffier) was reputed to have denied calling his creation after me -or denied creating it at all—I forget which. It does not matter, but I think we should give credit where credit is due. And it certainly is due to Escoffier.”

Had Escoffier been misquoted? Misunderstood? Or had he been playing the journalist, tired of discussing a dish he’d created decades earlier, tired of being associated with only one single dish? Who better to set the record straight than Melba herself.

The origins of the pêche Melba are well known in culinary circles and beyond, yet tracing the story through newspaper accounts in the decades following its invention reveals a curiously circuitous path shaped by those very stories over time, told by the 2 protagonists themselves, adding a few amusing twists - and several lingering questions - to a legend that has gradually transformed into myth.”.

Nearly two decades before being interviewed for La Toque Blanche, Escoffier offered a different version of his story, this one written by himself for the June 15, 1907 issue of L’Art Culinaire, the official publication of the Society of French Chefs. Over time, the event has, you will see, moved from the Hotel Savoy in London to the London Carlton to the Paris Ritz.

“It was at the opening of the Ritz Hotel in Paris,” he then wrote, “that Mme Melba one day confided to me her deep love for Pêche Cardinal with raspberry coulis, expressing her wish that I share the recipe with her — which I did with the greatest and most willing pleasure.

And it was while writing out the recipe that the idea of creating Pêche Melba came to me. But it was important to preserve the essential character of the preparation, while also seeking a new element that would not alter the flavor of the raspberry and peach, but rather enhance its delicacy.

I found that nothing could be more perfect than to rest the tender peach on a bed of vanilla ice cream and to then cover it in its cardinal’s robe — the raspberry coulis. From that moment, Pêche Melba was born, and it was at the opening of the Carlton Hotel in London that it “made its debut,” for the very first time.”

Here, Escoffier asserts that the Pêche Melba was a twist on the Pêches Cardinal, peaches cloaked under a bright red robe of raspberry sauce, that he had merely “enhanced” the dish with the addition of vanilla ice cream. In his memoirs, Souvenirs Inédits (published posthumously in 1985), he does, once again, make yet another claim: “I had found,” Escoffier concluded, “that simple peaches arranged over vanilla ice cream were nothing extraordinary, certainly not deserving such a title of noblesse; something was missing. So I added the delicate fragrance of raspberry. That is how, at the opening of one of the most famous high-society establishments in the world, I was able to dedicate — once and for all — the ‘Peach Melba’ to the marvelous artist.” On July 15, 1899, Escoffier, moving to the Carlton Hotel to set up the kitchens, hire and oversee the brigade of chefs, and create the menu (after being kicked out of the Savoy upon being charged with fraud), chose to feature the Pêche Melba for the first time. Here, Escoffier confirms (or at least implies) that the original dessert served to Nellie Melba was simply a sugared peach set atop vanilla ice cream — not a variation on the more colorful pêche Cardinal - the scarlet, fruity raspberry sauce, coming after, not before.

Escoffier—who would later feign no memory of creating the dessert for the diva—was, ironically, known to have recounted the story many times, both over meals to friends and colleagues and in various publications. One imagines Escoffier, never shy about elevating his own legacy, being rather puffed up by the fact that it was his peach dessert, not her decades of operatic fame, that ultimately made Melba a household name. Following her death in 1931, several obituaries acknowledged that the dessert bearing her name had earned her lasting notoriety as much as — if not more than — her illustrious singing career. As La Chronique Mondaine, Littéraire & Artistique observed, “her success as a pretty woman and as a singer was well known, but it’s at least curious to think that she may owe immortality to the peach that bears her name rather than to the brilliance of her artistic career.” A few months earlier, L’Action Française had noted with flair: “Melba, it’s almost comical to say, will leave a mark on the public’s memory as much by her singing as by the way she accommodates peaches in entremets... Habent sua fata les pêches! (Peaches have their own destiny!). Poor, charming Melba, will she forgive me from her final resting place for having thus diminished the reasons for the duration of her reputation?”

Who better than Escoffier, then, to describe this elegant creation himself, as he did in the August 7, 1930 issue of Le Petit Parisien? “Peach Melba is composed solely of tender, white-fleshed peaches, perfectly ripe; a fine vanilla ice cream (very creamy); and a raspberry purée sweetened just right... Line the bottom of a silver timbale or crystal dish with the vanilla ice cream. On this bed, gently place the peaches (peeled and lightly sugared), which you then cover with the red purée described above. Optionally, when in season, a few slivered fresh almonds may be sprinkled over the peaches (but never use dried almonds).

If one wishes to remain strictly traditional,” he adds, “the timbale should be embedded in a block of ice carved according to the imagination of the pastry chef, who finishes his creation with a delicate veil of fine sugar.’”

Of course, one of the world’s greatest chefs could not simply serve his peaches to a world-renowned opera chanteuse in a cup on a tray.

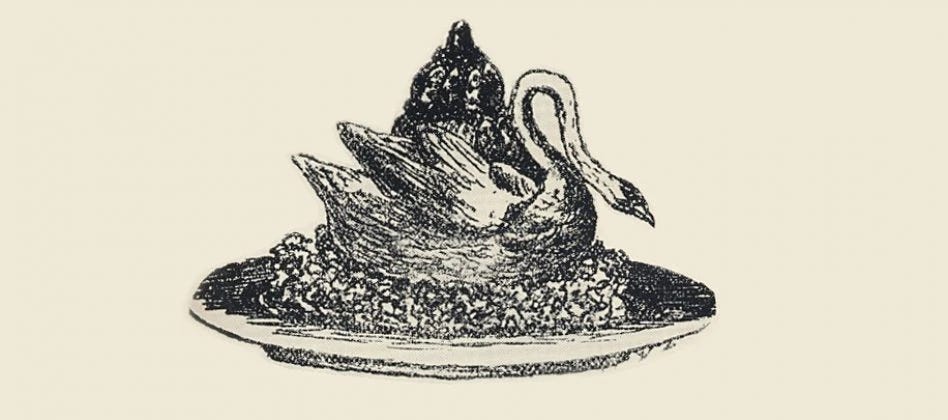

M. Escoffier, with a reputation to uphold as a culinary impresario and leading figure among French chefs, and wishing to show his admiration and thank her for having passed such a sublime evening under the spell of her magnificent voice after hearing her sing Lohengrin at Covent Garden, his thoughts went beyond the perfection of the dessert itself. He desired to present her with something gloriously majestic. As he wrote: “Madame Nellie Melba, a great Australian singer, sang at Covent Garden in London with Jean de Reszke in 1894. She lived in the Savoy Hotel near Covent Garden, at a time when I was in charge of the kitchens there. One evening, during a performance of Lohengrin, Madame Melba offered me two orchestra chairs….” Having been impressed with the representation of the swan, appearing in the first act of Lohengrin, Escoffier had carved a magnificent swan out of a block of ice and set this creature on a silver platter. Around the swan he arranged some lightly coloured blue spun sugar to imitate the water; between the wings he incrusted a large silver timbale containing the surprise: delicious, tender, ripe peaches peeled and poached, served on a bed of French vanilla ice cream, the whole topped with light haze of white spun sugar… “The dessert had its desired effect; the dessert was a success and he requested the honor of naming it after her and she accepted the dedication.”

Some years later, possibly 1899, Escoffier had the chance to once again see Madame Melba at the Ritz in Paris, where she spoke to him of the enchanting “evening of the famous swan peaches.” Mr. Escoffier told her that since then he was under the impression that plain poached peaches served on vanilla ice cream had nothing deserving such a title of noblesse; he felt that something was missing. He had then decided to add to it the fine perfume of purée of fresh raspberries mixed with a little sugar, and to sprinkle over it some finely shredded fresh green almonds.”

And yet….and yet… Nellie Melba’s own memory of the evening is just as vivid, immediate, and told with the kind of detail and artistic embellishments that only a clear, firsthand memory can offer. And it was, as you will see, nothing like Escoffier’s: “I was lunching alone in a little room upstairs at the Savoy Hotel on one of those glorious mornings in early spring when London is the nearest approach to paradise that most of us ever attain. I was particularly hungry, and I was given a most excellent luncheon. Towards the end of it there arrived a little silver dish, which was uncovered before me with a message that Mr. Escoffier had prepared it specially for me. And much as Eve tasted the first apple, I tasted the first Pêche Melba in the world….. Very soon afterwards, Pêche Melba was the rage of London.”

So, as you can see, the story of the creation of the pêche Melba swans around the pages of culinary history, from one grand hotel to another, from a dinner party of illustrious guests (often including the Duke of Orléans, Melba’s noble lover) to a dinner taken alone in her room, from the order of the addition of elements, to the presentation of the first dishful, to when it was named, and, funnily enough, each version comes directly from one of the two main characters.

The divine story of the pêche Melba is a perfect example of how culinary history unfolds — like genealogy for food and culture, it is rarely a straight line. It’s a winding, circuitous path, a puzzle in which the pieces aren’t just scattered, but hidden. You don’t just fit them together — you have to hunt them down, one by one, yourself.

So let’s close this funny, scrumptious little tale, fittingly, with a note of mutual admiration — a tribute shared between the two figures at the heart of it all: the grande dame of opera and the great master of the kitchen….

“And just as the voice of the illustrious artist charmed the harmonious echoes of both the Old and New Worlds, the exquisite fruit bears her name as a promise of infinite delight and enduring glory. Indeed, the Pêche Melba reigns as queen over the most sumptuous feasts, and its fame has crossed the seas.” - L'Art culinaire by Auguste Escoffier, 15 June 1907

“Escoffier is an artist in his own materials if ever there was one. I once tried to calculate exactly how much he would have made had he charged a royalty of one penny on every dozen Pêche Melba that were consumed, but I gave it up when I realized that it would total many millions of pounds. And not only was he the originator of Pêche Melba but of Poire Melba, Fraises Melba, and all the other dishes that followed in its train.” - Melodies And Memories by Nellie Melba, 1926

In recounting this story in his memoirs, Escoffier complained that while la Pêche Melba has become world-renowned, too often the recipe is altered, and “any departure from this rule detracts from the delicacy of this dessert.” Replacing the raspberry purée with another berry or adding a thickener like arrowroot to the coulis, or (heavens!!) topping the whole with Chantilly cream offended the great chef. “The result,” he stated, “is a Pêche Melba in name only, and not one to satisfy the palate of a connoisseur.”

Pêche Melba

Serves 4

You don’t have to poach the peaches in the sugar syrup; Escoffier simply plunged the ripe peaches in boiling water for just a minute, peeled them, halved and pitted them, and dusted the peach halves with sugar and let them set. You can certainly do this Escoffier’s way, if you like. In that case, gently heat the raspberries with a couple tablespoons of water and a tablespoon or two of sugar (to taste) over very low heat, stirring and pressing until the sugar is dissolved and the raspberries are puréed.

Don’t tell Escoffier that I suggest adding toasted slivered “dried” almonds and whipped cream.

4 ripe peaches

2 cups (500 ml) water

2 cups (400 grams) sugar

1 vanilla bean/pod

9 ounces (250 grams) fresh or frozen raspberries

3 tablespoons of the sugar syrup (once the peaches are cooking in it)

Squeeze of fresh lemon juice

Creamy vanilla ice cream

Lightly toasted slivered almonds and a few fresh raspberries for garnish, optional

Very lightly sweetened whipped cream, optional

Peel the peaches: Bring a pot of water to the boil; make a single slit in the skin of each ripe peach then gently drop the peaches into the boiling water. Leave the fruit in the boiling water for only 1 - 2 minutes until the skin around the slits begin to pull back. Using a slotted spoon, lift the peaches out of the water and onto a plate. When the peaches are cool enough to handle, gently peel off all the skin. Separate each peach into two halves, discard the pits, and make the sugar syrup.

Make the sugar syrup: Combine the 2 cups (500 ml) water and 2 cups (400 grams) sugar in a pot of large saucepan - the pot should be just large enough to hold the 8 peach halves and have them all submerged in the liquid.

Using a paring knife, split the vanilla pod vertically down the center and place in the sugar water - using the point of the knife, you can scrape out the seeds and add them with the split pod to the pot separately.

Poach the peaches: Bring to the boil, stirring. When the sugar is dissolved, slide the peach halves into the boiling liquid, lower the heat under the pot so the liquid is at a low boil or simmer and cook the peaches for 20 minutes. You can either leave the peaches to cool in the syrup off the heat or immediately remove the poached peaches to a bowl. Allow the peaches to cool then put them in the refrigerator to chill (if you leave the peaches to cool in the syrup, scoop them out of the liquid into a bowl or a Tupperware container before putting in the refrigerator).

Make the raspberry sauce/coulis: While the peaches are poaching, place the raspberries in a small saucepan with either 3 tablespoons of the boiling sugar syrup or 2 tablespoons water and 1 tablespoon sugar (I like making these with the sugar syrup). Squeeze in about a teaspoon of lemon juice. Place the saucepan over low heat and stir and mash (with the back of a spoon or a wooden spoon) the raspberries as they heat until they are completely softened and mashed - they do not have get hot or boil, just soften and cook. If the raspberries cooked in water and sugar, taste and add more sugar if you like, then continue heating and stirring until the sugar is completely dissolved.

Place the raspberries and any liquid they have released into a fine mesh strainer over a bowl to catch the liquid. Using a spoon or a soft plastic spatula or bench scraper, press the most juice out of the cooked raspberries as possible. Discard the seeds and refrigerate the fruit coulis or juice to chill.

Prepare the garnish: If you like, toast a handful of blanched slivered almonds in a dry frying pan quickly over low heat then immediately transfer them to a plate to cool just as they begin to color. Whip some heavy cream in a chilled bowl until thick, adding only enough powdered sugar as needed to lightly sweeten. Refrigerate the whipped cream until ready to serve.

Serve: Place a generous scoop of creamy vanilla ice cream in a bowl or dish. Place 2 halves of the poached peaches atop the ice cream. Spoon raspberry coulis on top - this amount of coulis is perfect for 4 servings. Top with whipped cream, if you like, some toasted almonds, and a few fresh whole raspberries.

Thank you for reading and subscribing to my Substack Life’s a Feast. Please leave a comment, like and share the post…these are all simple ways you can support my writing and help build this very cool community. If you would like to further support my work and recipes, please consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Oh Jamie, this is delightful and I don’t care if not a single word from either Melba or Escoffier are outright lies!

And for me, personally there is another, very obscure connection, one that connects the name Melba and France.

I grew up being very close to a girl and then woman named Cheryl Frink. I was born a mere week earlier and when I was about two weeks old my parents took me to the Frink home, so Cheryl was my first date. 😊

Cheryl and I had the enormous privilege, from grades 5 through 8, of being taught French by the amazing Madame Anne Forman, a Parisienne who, I am relatively certain, had married an American GI after World War II. Since Neither my first name, nor Cheryl’s translate easily into French (much less are easily pronounceable by the French!) we were both called by our middle names in French class. Mine was Robert, hers was Jeanne.

Cheryl’s mother was called Jean but her full name was Melba Jean Frink, née Zehr. Hence Cheryl was called Jeanne! And I was Robert, both with the correct Parisien accent of course.

I have never known how Cheryl’s mother came to be named Melba Jean, but now I am determined to find out. Sadly Cheryl died in January of 2023, succumbing to cancer. I still miss her deeply. In any event I will inquire of Melba Jean (she goes by Jean) or her second daughter, Deborah. (I believe Jean is still living.)

But … there’s more - the REAL connection(s)!

By the time we had both graduated from high school, I was nearly fluent in French; all I needed perhaps was to spend several months to a year immersed in French. However, I went on to study biology in university.

Cheryl majored in French in university, including a year of study in Grenoble. Subsequently she achieved a Master’s degree, including at least one semester at the Sorbonne. She became a high school French teacher and travelled back to Paris almost every year during Summer break, as well as Grenoble to visit a close friend she had met in Grenboble.

After many years of going our separate ways and after a bad breakup with a girlfriend, Cheryl and I connected again. It was a balm I sorely needed. She had occasionally urged me to go to Paris and that planted the seed for my first trip. When my newly minted PhD in linguistcs son took his first job at École Normal Superieur in Paris, I took the opportunity to go. It was the shortest week of my life! But I was hooked.

On my last full day we went to l’Orangerie where I saw the Monet lily panels, which caused me to nearly faint with wonder and pleasure. Then we took the #69 bus to the 7th to visit la tour Eiffel. On the bus we were chatted up by a lovely vielle dame. Af the final stop, she too got of the bus and INSISTED we come to her ground floor apartment where we had a pleasant visit, then she walked us to the Champs de Mars.

After we inquired her name, she asked mine. She asked mine. OF COURSE she couldn’t pronounce “Earl”, so I told her my middle name was “Robert”, to which she replied “Oh, BOB!” And nearly shouted, “Non, JAMAIS Bob!”

After ENS my son went on to teach at Paris Cité for a few years, and is now a professor at University of Toronto, along with his fiancée, who is from Francophone New Brunswick, also a PhD professor at U of T.

My daughter, who did her last year at university in Nantes, went on to be an elementary level teacher at a French immersion school in Toronto.

So there you have it and I swear every word is true … how a post World War II love affair in Paris changed the lives of not only two people, but my children, my Francophone grandchildren, my lovely Cheryl and the thousands of pupils she graced with her remarkable life.

Now I’m off to find out how Cheryl’s mother was named Melba Jean, as I anxiously await peach season so I can make Pêche Melba, which will forever bring back these wonderful memories.

Merci, Madame Foreman

My dad was stationed in France in the early 1950s (brother born there). After returning to America, we had Peach Melba (no secret almonds) and maybe a little too common (just ice cream) on fresh orange peaches with raspberries. The taste of summer!

I now live in Japan, where they have lovely white peaches, which are delicious as Peach Melba. But I still prefer the slightly stronger flavor of the orange peaches. I will also try boiling in the the sugar syrup to get closer to the namesake.

Thank you for a fun read, Jamie.