It was he who had an omelette sprinkled with fine crushed pearls served to him at his table. - writing of René de Villequier, Henri III’s favorite, in Les Cérémonies Tenues et Observées à l'Ordre et Milice du Sainct Esprit (Ceremonies Held and Observed at the Order and Militia of the Holy Spirit), 1579

“Omelette, the traditional dish, the classic family treat, and the one thing all men can come together and agree on….”

That one simple sentence written in a column in Nouveauté : modes, ouvrages, variétés, roman women’s magazine in the January 30, 1938 issue perfectly illustrates the topic of today’s post, albeit NOT dusted with crushed pearls. The simple omelette is the rare dish that easily crossed social lines throughout the centuries, a staple of both the upper classes and the lower. And everyone in between. Eggs were easily accessible, butter or oil usually was, as well. It was a cheap dish, easy to make, and comforting. And the omelette was, as we shall see, the blank slate for a million fillings and flavors.

“Among the countless recipes published on the various ways to prepare eggs, the best-known and most popular is undoubtedly, after the boiled egg, the succulent omelette. The mere sight of a well-prepared, evenly-colored omelette, cooked to perfection, tender and delicate, is enough to awaken the recalcitrant appetite of a jaded gourmet. It's the main course at a rustic lunch, the providence of travelers in distress and the resource of hoteliers caught off guard by the arrival of unexpected guests. It's an appetizing snack, a varied treat, an improvisation. In a word, it's the dish of the day every day.” (250 Manières d’Accommoder et de Manger les Oeufs by Alfred Suzanne, 1903)

People have been making omelettes for as far back as historians can tell, as far back as Greco-Roman times. In France, we pick up their trace in the Middle Ages, around 1300 with the single mention of une grande allumelle d’oeufz fritz au blanc lart - a large omelette of eggs fried with lard or bacon in Guillaume Tirel’s (aka Taillevent) Le Viandier. The 1393 Ménagier de Paris, Albertano da Brescia’s tome written to instruct women in the domesticity of a happy home, made a savory omelette, also written allumelle, with cheese, herbs, and spices, as well as a simple sweet version with sugar. Allumelle, it seems, comes from the old French allumelle or lamelle, a word referring to a “lamella”, something thin and flat, like the blade of a knife or sword (lame, in today’s French).

François Rabelais’s endearing comparison of a perfect couple to an omelette in Le Quart livre des faictz et dictz héroïques du bon Pantagruel, published in 1552, writes the word homelaicte (“om-e-lay”), the pronunciation having evolved to something very close to omelette: “In such an affair, he called her my omelette. She called him my egg; and together they were like an egg omelette.”

But the origin of the word is disputed. François de La Mothe Le Vayer, 17th century philosopher and historian, referred to the omelette as “œufs meslez” or “oeufs mêlés” translated as mixed eggs; ancient Romans referred to it with the Latin “ova mellita”, again mixed eggs. “Oeufs mêlés” is a pretty easy jump to “omelette” more than likely passing by homelaicte.

But by the time the French move out of the Middle Ages and into the modern era, the omelette - accurately and concisely defined in the 1767 Dictionnaire Portatif de Cuisine as "a dish consisting of scrambled eggs beaten with various seasonings and pan-fried in butter or oil” - is a pretty common dish.

François Pierre de la Varenne devotes an entire chapter of Le Pastissier François (1653) to Diverses Manières de faire les Aumelettes (Various Ways to Make Omelettes). From a simple omelette (Aumelette simple), to omelettes filled with everything from cheese to asparagus, from kidneys or fish to an intriguing Aumelette à la Turque, an omelette filled with chopped rabbit meat blended with finely chopped nuts (chestnuts, hazelnuts, almonds, or pine nuts), fines herbes and (undefined) spices. In all, la Varenne includes 22 recipes for omelettes, both savory and sweet. Curiously, la Varenne has a recipe for omelette farcie in his earlier cookbook Le Cuisinier François, what we would consider a very modern idea, indeed, of making an omelette as a way to use up leftovers, in this case a farce or filling.

Nicolas de Bonnefons saw fit to introduce his chapter on the omelette - it is now 1654, just a year after Pierre de la Varenne published his cookbook, and de Bonnefons is indeed writing omelette - in Les Délices de la Campagne with precise instructions on cooking this delicacy. “You must have a pan that is only used for omelettes,” he begins, “and don't scour it, only wipe it with a white (clean) towel before and after making an omelette.” He advises melting a good lump of fresh butter - “salted butter never makes omelettes as nice as fresh better” - and heat until it no longer bubbles and fizzes, until it stops making noise and begins to color, when one adds the well-beaten, lightly salted eggs. He recommends cooking the omelette over a high heat so that it takes on a beautiful color without being too cooked in the middle, “un peu baveuse” - removing it from the heat when it is still a little runny, or baveuse….drooling.

“In the beaten eggs,” de Bonnefons adds, “one can add chopped parsley, chives, thyme, marjoram, elderflowers, and other fines herbes to your taste. Cheese must be added in small dice or strips to the eggs in the pan once the omelette has begun to cook; throw the cheese on top of the eggs or it will stick to the pan.” Finally finishing with “To make an ‘excellent and delicate’ omelette, replace half the egg whites with cream.”

The omelette was crazy popular, post-Middle Ages; chefs are now including a wide variety of recipes for omelettes in their cookbooks, cookbooks only destined for royal kitchens and noble tables. Not only de la Varenne (Le Cuisinier François, 1651)) but Pierre de la Lune (Le Cuisinier,1656), François Massialot (Le Cuisinier Roïal et Bourgeois, 1705), and L'Escole Parfaite des Officiers de Bouche, an instruction book for chefs, sommeliers, pastry chefs etc serving only the finest houses, the best tables, 1662, include a multitude of recipes for both savory and sweet omelettes. Omelettes are not only filled with fresh herbs, kidneys, or cheese, but now with lentils or raspberries, artichoke hearts and mushrooms or fish milt or candied lemon peel cooked in white wine and chopped with almond macarons, sweetened and flavored with orange flower water. Simple omelettes with sugar or filled with butter-fried bread croutons are fairly common staples in cookbooks now, too.

Fresh pimento: matricaria, chamomile flowers, and, after having joined everything together, fricassee it in a frying pan with lily oil, then, having incorporated the whole with eggs, make an omelette, which should be applied hot to the stomach. - Histoire Générale des Plantes, 1615

Blood flow: Hydropiper maculata dulcis, eaten as an omelette, cures blood flow. - Journal des Voyages de Monsieur de Monconys, 1677

By the time César-Pierre Richelet put together the Dictionnaire François in 1706, the word had not so much evolved as finally settled down. “Omelette, aumelette, amelette…either is used but the customary word is omelette. These are eggs broken, beaten, and cooked in a pan with butter. Omelette à la Celestine is a very particular omelette made by the Celestine monks using 12 eggs and made in a taller, narrower pan than a pan used by the bourgeois to create a much thicker omelette. All omelettes made thicker than the average omelette are called omelette à la Celestine.”

The 19th century arrives with the same omelette enthusiasm, cookbooks containing more or less the same selection of recipes, including the omelette à la Celestine - now a dish of several small omelettes, each tightly rolled into a log (or muff), placed together in a dish, dusted with sugar and heated until iced - and the omelette soufflée - in which the whites are separated from the yolks, beaten until stiff, then folded into the sweetened and flavored beaten yolks and finished cooking in the oven, creating a highly risen, fluffy soufflée-like egg omelette. The omelette has now worked its way down into household cookbooks boasting economy while remaining a popular dish in cookbooks written for more elegant homes. Omelettes with truffles to omelettes with apples, from omelettes now filled with tomatoes or potatoes or onions to complete vegetable stews or an elegant omelette stuffed with a mixture of truffles, asparagus tips, mushrooms, and a purée of foie gras. The varieties are, indeed, endless.

Only Henri Babinski, known as Ali-Bab, sacrifices quantity for quality in his 1907 masterwork of 5,000 recipes Gastronomie Pratique. “It may seem trivial to give a recipe for an omelette,” he writes, “because everyone thinks they know how to make one. In reality, however, there's no shortage of people who have never eaten a really good omelette.” He limits his entry to “clarifying the details and tricky points;” he doesn’t bother describing or offering innumerable variations on the omelette, he insists on focusing only on the preparation of the simple omelette, l’omelette au naturel, because “he who knows how to do this one knows how to do them all.”

And that, for Ali-Bab, means starting with the freshest eggs possible; the quality of an omelette relies almost uniquely on the quality of the eggs. He gives minute details on the depth and diameter of the ideal pan, the weight of each egg used, the quantity of not only the milk and butter but also the salt and pepper to the gram. His instructions are precise and heaven help anyone and their omelette if each bit of information isn’t followed to a tee. “By following these instructions step-by-step,” Babinski insists, “you'll have an omelette that's beautifully golden on the outside, moist and juicy on the inside, as light and fluffy as one could wish for.”

It’s too bad that Louis XV didn’t have this book available to him 2 centuries earlier; he enjoyed making omelettes with his own royal hands, most particularly a royal omelette with rooster crests and carp roe created for him by François Marin. And yet, for his reputation, as the Countess Madame du Barry, the king’s official mistress, wrote in her memoirs, "You understand, without a doubt, that Louis XV promised me an omelette of his own making. In fact, he loved cooking and taking care of everything that went with it. Les Dons de Comus (François Marin, 1739) and La Cuisinière Bourgeoise (Joseph Menon, 1746) were the works of our literature that he read with the greatest pleasure….but (the omelette) was burnt to a crisp. All present looked on in dismay.” Needless to say, it was eaten anyway. No one says no to a dish made by the king.

Babinski does offer one curious recipe which he calls a Symphony of Eggs, an omelette for 6 diners: a thin omelette is made of 4 eggs which in turn is filled with 2 finely chopped hard boiled eggs and 6 poached eggs; the omelette is folded over this double egg filling, slid onto a platter and served. The host or hostess must make sure that each guest has a slice of omelette containing one whole poached egg. Alternatively, the cook can prepare 6 individual omelettes, each containing a bit of the chopped hard boiled eggs and one poached egg. A sauce boat of either tomato sauce, béchamel, or cream tarted up with a bit of lemon juice.

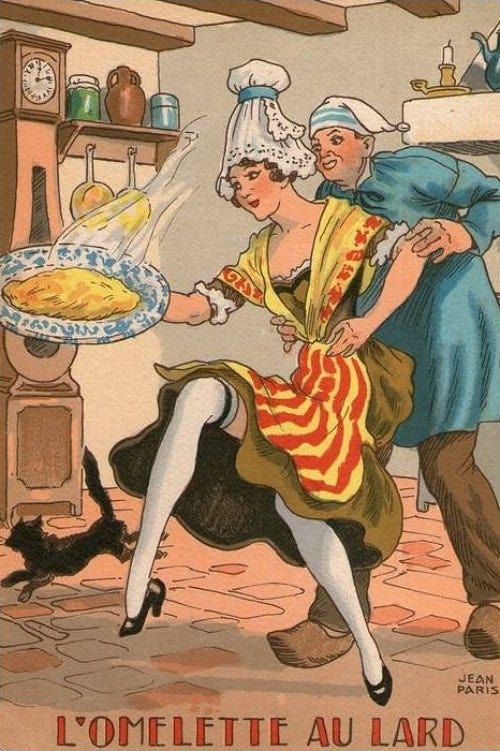

The 20th century chefs are no less enthusiastic about the omelette, adding onto all the old staples by experimenting with new ingredients from herring or anchovy omelettes to coffee or chocolate omelettes. Omelettes à la Jardinière (“make a ragout of all sorts of vegetables and fresh herbs), l’omelette Normande (apples and Calvados), omelette Rossini (truffles and foie gras), omelette à la Ménagère (filled with macaroni)… Curnonsky insists that the omelette has become a local specialty in 5 different regions of France: Brittany (carp roe and tuna), Périgord (truffles, of course), Lorraine (lardons or bacon and cream, like the quiche), Limousine (salty bacon, mushrooms, parsley and chervil), and Normandy.

A recipe that particularly intrigued me during my research was the apple omelette. We are not used to eating sweet omelettes and I was curious enough to try it. The apple omelette was one of the earliest versions of the omelette in French cookbooks when sweet omelettes were as common as savory; François Pierre de la Varenne has a recipe for Aumelette aux Pommes in 1653 in Le Pastissier François. And so I made it.

I don’t know if I will ever eat a savory omelette again. Although a dessert, we ate it for lunch and what a damned fine lunch an apple omelette makes.

Omelette aux Pommes - Apple Omelette

For 2 people I used

2 small or 1 ½ medium apples, Golden is ideal

1 to 2 tablespoons butter

1 tablespoon granulated brown sugar

4 large eggs

Pinch salt

1 tablespoon heavy cream

Fine lemon zest, from about ½ a lemon, more if you like

Peel and core the apples and slice thinly - not too thin as you want them to hold their shape and not break when sautéing.

Melt a tablespoon or more butter in a frying or sauté pan; when it is melted and bubbling, add the apple slices in a single layer. Dust with a tablespoon of granulated brown sugar. Cook over medium heat (lower it if you’re more comfortable), carefully flipping the slices and moving them around in the pan for even cooking, until they are tender through. This only takes about 5 minutes or less.

While the apples are cooking, break the eggs into a bowl and whisk with a pinch of salt, the cream, and the lemon zest.

When the apples are perfectly tender, make sure they are spread in a single layer across the bottom of the pan; add a bit more butter if you feel it is needed to keep the eggs from sticking to the pan. Pour on the beaten eggs, pouring them evenly over the apples. Allow the omelette to cook until the bottom of the omelette is a nice golden brown; using a spatula - once the omelette begins to set - push the edges of the omelette away from the edges of the pan, allowing liquid egg to slide underneath. Also try to slide the spatula under and around the omelette to keep it loosened from the bottom of the pan.

Once the bottom of the omelette is cooked and the eggs on top and around the apples are barely set but a bit still runny, try to flip half the omelette over the other half. You can see in my photos that I am not very good at this step but it doesn’t really matter.

Slide the omelette out of the pan and onto a serving platter. Dust with more granulated brown sugar and serve.

Thank you for subscribing to Life’s a Feast by Jamie Schler. Please leave a comment; your opinions and feedback help me create the content you want and your stories help build our community. You can support my work by sharing the link to my Substack with your friends, family, and your social media followers. If you would like to see my other book projects in the making, read my other essays, and participate in the discussions, or just support me further, please upgrade to a paid subscription.

Just made it, added....dusting of cinnamon to cooking apples, fresh parsley to the eggs.

Once close to set, sprinkled sharp cheddar across, then about 2 minutes broil to finish setting and melt cheese (a new England twist).

Fan-freaking-tastic!!!

Thank you

yum, I love sauteed apples. I've done a berry omelette, it's lovely to step outside the usual savory fillings.