Navettes de Marseille

Taste the flavor of my golden navettes! - François Delille, Marseille, 2 février 1881

A tradition is all the more enduring when it is dear to the palate of our fellow citizens. - Les Tablettes Marseillaises, February 1914

France is still, at heart, a Catholic country, despite its strict laws of — and commitment to — laïcité. The calendar remains punctuated by religious feast days and saints’ days, whether or not the French still go to church or even remember the origins and significance of these dates. This is not necessarily a bad thing, as each of these holidays is marked by pastries — traditional, local, and regional — that go hand-in-hand with celebrations or have outlasted observance itself. Galette des Rois or Gâteau des Rois for Epiphany; Bûche de Noël, Pompe à l’huile, Zimtsterne for Christmas; gaufres or beignets (bottereaux, merveilles, bugnes, etc) for Mardi Gras; le Colombier for Pentecost; les corniottes for Ascension, crêpes for Candlemas, or various specialties for saints’ days, like croquendoules for Saint Martin’s feast day. To name a few.

La Chandeleur, or Candlemas, the feast of candles, is one of those holidays whose religious rituals have largely faded, their memory preserved instead through the foods that continue to be made and shared. In France, the holiday, celebrated on February 2, endures above all in the ritual of making and eating crêpes.

And yet, while French homes all across the country are whisking eggs, milk, and flour, pulling out jars of jam and chocolate cream, the southern city of Marseille marks la Chandeleur with navettes, slender, boat-shaped biscuits perfumed with orange blossom water and local olive oil.

Candlemas, like Christmas and Epiphany, was originally a pagan and Latin festival before it was embraced and adopted by early Christians. The Romans celebrated Lupercalia from February 13 to 15 in honor of Faunus, the god of fertility and livestock; candles were burned to honor and protect the dead, to purify and mark the light of the new year as the days began to grow longer. In the latter half of the 5th century, the Christians used the celebration to mark the Presentation of Christ in the Temple, celebrated forty days after Christmas, on February 2. According to the Gospel of Luke, this was when Mary and Joseph brought the infant Jesus to Jerusalem, and when Simeon recognized him as the “light to enlighten the nations” — a moment that gave rise to the blessing of candles and candlelit processions. In 494, candles were associated with Candlemas by Pope Gelasius I, the first to organize torchlight processions on February 2. In a letter to Senator Andromachus, he expressed his desire to restore the Lupercalia and argued for their purifying power.

La Chandeleur also sat at the pivotal point in the agricultural year, when households were nearing the end of their stored grain from the previous year, and before the fate of the wheat crops, which had been planted in the autumn, could be assessed. And so, by the Middle Ages, this festival became charged with prayer and rituals, linking the religious calendar with the rhythms of wheat cultivation and rural survival. Making crêpes with wheat flour was therefore highly symbolic: an offering of thanks for what remained, a hopeful gesture toward the next harvest, and a way of ritually “setting wheat in motion” again before the agricultural cycle resumed in earnest. And like the galette eaten on Epiphany, the roundness of crêpes represent the sun, light, purification, and hope for the new season.

But Marseille, a bustling southern French port city rather than a farming town, followed a different rhythm and a unique custom. Candlemas traditions reflect the city’s maritime character instead.

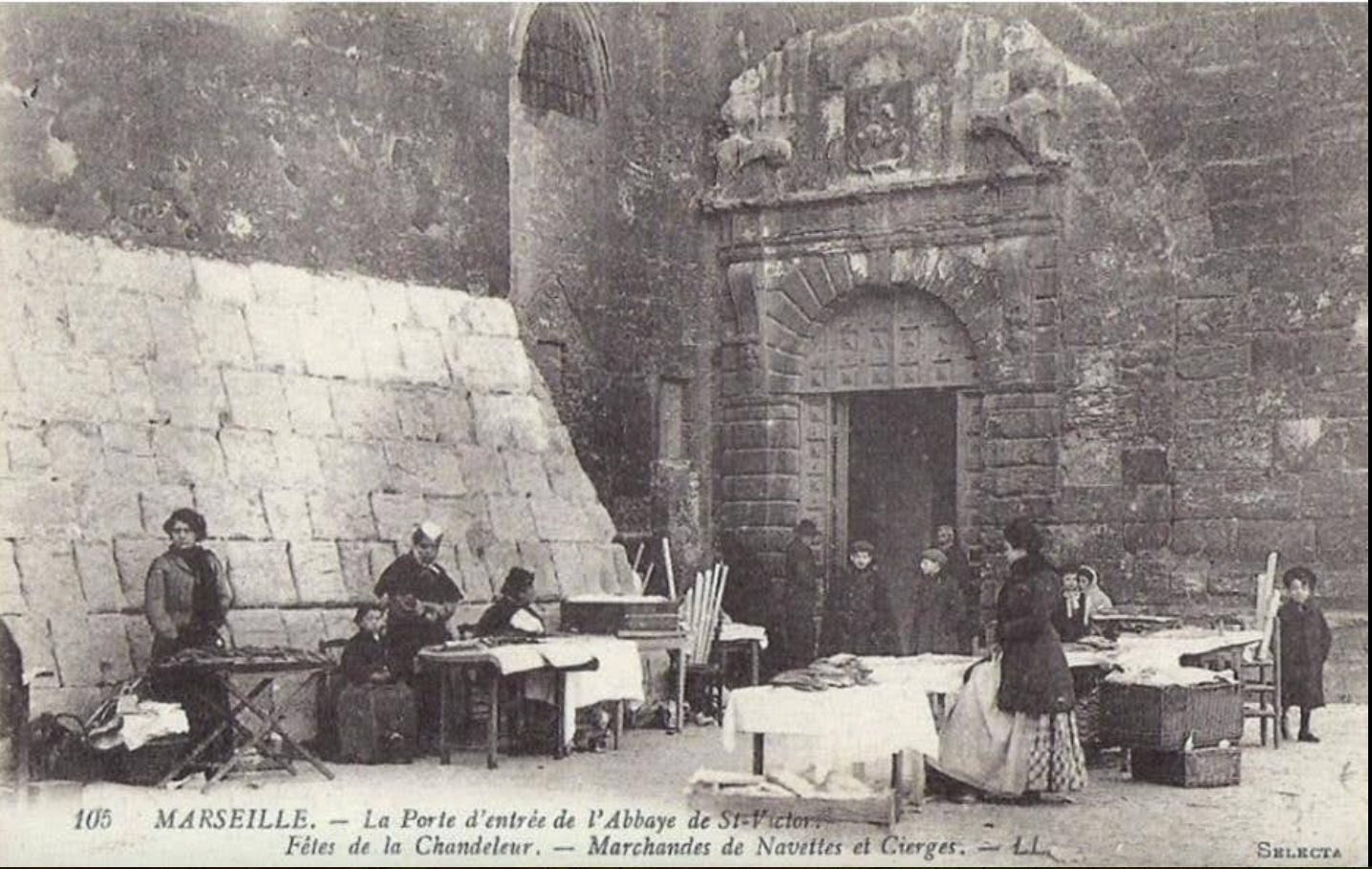

In Marseille, Chandeleur is inseparable from the Abbey of Saint-Victor and its Black Virgin, La Vierge Noire, a medieval statue carved in the 13th century from dark walnut wood, which anchors the feast firmly in the city’s religious and cultural history. On Candlemas, pilgrims traditionally gathered at Saint-Victor — one of the city’s oldest churches — to venerate the medieval statue associated with protection, fertility, and safe passage. Candles were blessed in her presence, reinforcing the day’s symbolism of light, purification, and renewal.

But why navettes instead of crêpes? Marseille, a singular city with a singular history, follows a unique religious story. According to one of Provence’s most enduring legends, a boat landed on these shores, on the banks of the Old Port in Marseille, in the first century carrying Mary Magdalene, her sisters Marthe, Jacobe, and Salome — the Saintes-Maries — along with Lazarus and other early Christian figures, fleeing persecution after the Resurrection. The navette’s elongated, boat-like shape is said to commemorate that arrival, an echo of Marseille’s ancient, maritime origins.

“All the assistants carried green candles in their hands, which were blessed by the celebrant and then lit from the new flame, blessed on that day in the church of Marseille as on Holy Saturday. On leaving, everyone hurried to buy cookies called navettes at the abbey gate, which were shaped like little ships, perhaps in memory of the miraculous voyage of Saint Lazarus and his blessed sisters.” - Saint-Victor de Marseille et Notre-Dame de la Garde, Théophile Bérengier, 1892

According to the professional publication Le Boulanger-Pâtissier, “On November 24, 1781, the chapter of Saint-Victor Abbey authorized Antoine Lauzière, a baker and pastry chef, to build an oven at 136 Rue Sainte. He made navettes for Candlemas in 1782, an easily portable, long-lasting cookie to provide sustenance for pilgrims. These cookies soon became so popular that people came from all over the city to buy them. All the bakers in Marseille soon followed their colleague’s example. Soon, it became common practice to make navettes for Candlemas.”

Like the gâteau nantais — and like many confections with religious origins — navettes belong to the family of gâteaux de voyage: baked goods designed to keep well and for a long period of time, to travel, and to nourish those on the road or at sea, like macarons, madeleines, and financiers. The navettes were indeed well suited for pilgrims visiting Saint-Victor, coming from near or far.

The February 5, 1914 issue of Les Tablettes Marseillaises, made the claim that 250,000 navettes are produced by the ovens of this same ancient bakery every day on and following the Chandleur “while we let the “Black Madonna get some fresh air”…and as the festivities last a week, it means that more than 2 million navettes are baked in that oven, “a tradition is all the more enduring when it is dear to the palate of our fellow citizens.” The good people of Marseille must stock up on these fragrant little biscuits, storing them away to be eaten over the course of the whole year until the following Candlemas when the ritual begins again.

Navettes are true gâteaux de voyage, made with local olive oil rather than butter, which gives them their characteristic firmness — a texture best softened by dipping them in milk, coffee, or tea, or, for adults and sailors, rum or Madeira.

Navettes de Marseille

First published in my cookbook Orange Appeal (Gibbs Smith, 2017)

½ cup (100 grams) granulated white sugar

1 large egg

1 rounded teaspoon fine orange zest

3 teaspoons orange blossom or orange flower water

3 tablespoons olive oil

¼ teaspoon salt

1 ¾ cups plus 2 tablespoons (250 grams) all-purpose flour

Milk for brushing the cookies before baking

In a medium mixing bowl, beat the sugar and the egg on medium-high speed until pale, thick, and creamy, about 2 minutes. Beat in the zest, orange blossom water, and olive oil.

Stir the salt into the flour and then beat about ⅔ or so of the flour into the batter in 2 or 3 additions.

Finish folding the flour in by hand, kneading until all - or as much is needed for a smooth dough - of the flour has been added and a smooth dough has developed. Form the dough into a ball, wrap in plastic wrap, and refrigerate for 1 hour.

Preheat the oven to 350° F (180° C). Line a baking sheet with parchment paper. Take the dough out of the refrigerator and slightly flatten the ball into a disc. Cut the dough into 12 even wedges.

Roll each wedge into a 3-inch-long (7 cm) oval log and place on the prepared baking sheet.

Shape the pieces of dough into small “navettes” or little boats by pressing to flatten just a bit, and pinching the 2 ends into rounded points. Make a 2-inch (5 cm) slit down the center of each with a sharp knife, cutting only halfway down into the dough, and carefully push the slit open slightly.

Brush each cookie lightly with milk.

Bake for 20–25 minutes, or until golden; the tips and undersides should be a deeper golden brown. Remove from the oven and allow the cookies to cool on a rack. Store in a covered container.

Thank you for reading and subscribing to my Substack Life’s a Feast. Please leave a comment, like and share the post…these are all simple ways you can support my writing and help build this very cool community. If you would like to further support my work and recipes, please consider becoming a paid subscriber.

When I think of navettes, I immediately smell blooming orange trees, feel the warmth of the sun slipping through the leaves. Fingers knead the dough. Time slows down. The sugar turns into tiny crystals of light. The dough takes shape and begins to tell its story. The olive oil reassures, the orange blossom invites deep breaths. Navettes ask for time, for slow tasting. Each bite is an emotion that takes you by the hand and leads you to Provence. They stay in your heart, not just on your palate, teaching you that goodness and beauty often dwell in the simplest things and gestures.

- Suzette Monet

Fascinating. Excellent research.

Thank you.