Yes, kind and charming women, I can give you some new ideas in gourmandise (deliciousness); and my recipes will have nothing that is not worthy of your fine and delicate taste. - Marie-Antoine Carême, Le Pâtissier Royal Parisien, 1815

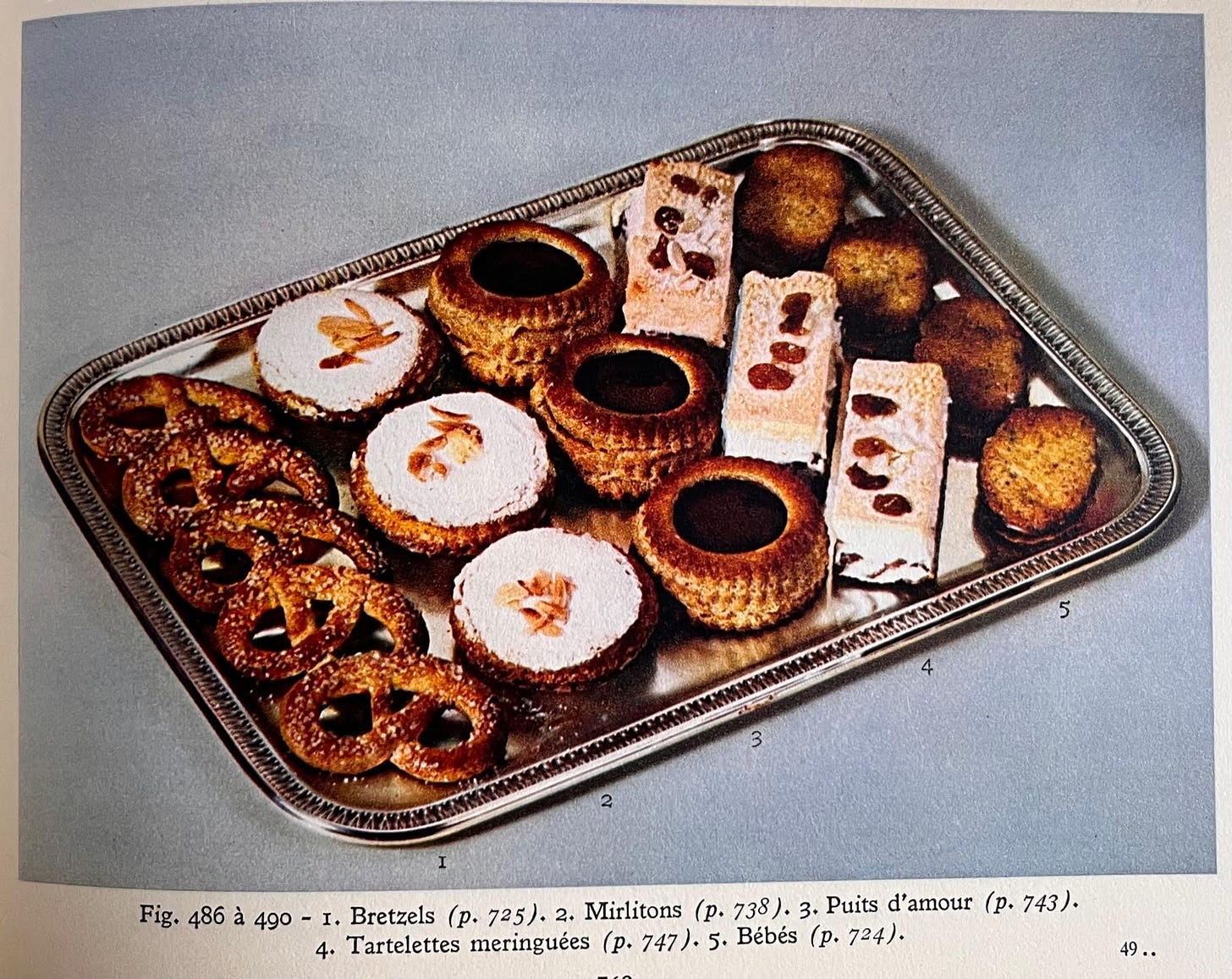

Joseph Favre gives the best definition of the mirliton in his 1895 Dictionnaire Universel de Cuisine Pratique: “Name given without reason to a small round tartlet, revealing nothing about the mirliton, which is a long-shaped instrument.” He then notes “Mirlitons vary only in the composition of the filling.”

A year earlier, Pierre Lacam is quoted in the professional journal of the French Chefs’ Society, L’Art Cuilnaire "Lyon had a speciality of excellent mirlitons that are nothing like those from Rouen.”

And in 1929 one M. Leblanc writes in his Nouveau manuel complet du patissier ou Traité complet et simplifié de la patisserie de ménage, de boutique et d'hôtel (Complete and simplified treatise on household, pastry shop, and hotel pastries) “By this name (mirliton), we don't mean the long, ridiculous flutes sold in the guinguettes of Paris, but small round cakes in puff pastry, on which is spread a layer of crushed macaroons, or an almondy preparation that bulges pleasantly.”

So that’s pretty clear.

In fact, there are two different pastries called mirliton, those originating in the town of Pont-Audemer in Normandy which are, in fact, shaped like those “long, ridiculous flutes sold in the guinguettes of Paris” - like kazoos or those party favors called, appropriately, party horns that one blows into as a paper “tongue” unfurls. These mirlitons, supposedly created by Guillaume Tirel, better known as Taillevent, chef for the French court and author of the first cookbook in French, Le Viandier, in 1340, are made from a paper-thin, crisp cookie dough baked on a tube, the cookie tube filled with a nutty cream filling, the ends then dipped in chocolate.

But today we are going to talk about the mirliton de Rouen and its kith and kin, those small, round tartlets, a puff pastry shell filled with many a variety of fillings, as Favre points out, but most usually an almondy cream filling, sometimes garnished with a bit of jam.

While the tube-shaped mirliton was possibly named after the child’s flute, the individual round tartlets might very well have been named after another mirliton, the old Louis d’or gold coin made for Louis XV in the 1720s, originally called a Mirliton les Louis d’or. Which was a total flop.

But that’s really neither here nor there.

According to the dictionary La Langue Française, the etymology of the word mirliton is unknown. “Attested as early as 1738 in the sense of “currency”, 1745 in the sense of “flute” and in 1845 in the sense of “pastry”. It's probably one of those words taken as a refrain, which mean nothing in themselves, and depend on the singer's whim, like biribi, tralala, lanlaire, etc.”

Actually, the first time the word was used to designate a pastry was in Grimod de La Reynière’s Almanach des Gourmands in 1812. He writes, without ever once describing it, “M. Thomas, a well-known pastry chef in rue de Grammont, Paris, makes Rouen-style mirlitons, which are, so they say, for we do not guarantee this fact, singularly sought-after by connoisseurs; the mirlitons of Rouen…owe their superiority to this delicious cream from Sotteville, which has no equal in the four parts of the world.” So, he not only doesn’t tell his readers what the mirliton is, but he hasn’t even gotten to M. Thomas’ pastry shop to taste one.

One of the first cookbooks to offer recipes for mirlitons - specifically mirlitons de Rouen and mirlitons à la Parisienne, was L’Art du Cuisinier by A. Beauvilliers in 1814. His tiny puff pastry shells were filled with a cream made of beaten sugar and eggs, melted butter, perfumed with a bit of orange flower water, and the whole dusted with sugar before baking, which will form a paper-thin sugar “crust”. The mirlitons à la Parisienne differ from those of Rouen with the addition of beaten egg whites and a pinch of flour folded into the creamy filling, making for a lighter, puffier mirliton.

Within a year, our old notable friend, Marie-Antoine Carême, dedicated a short chapter to the mirliton in his Le Pâtissier Royal Parisien. He begins with mirlitons à la fleur d’oranger, adding crushed macarons and “fleur d’orange pralinée en poudre'', a powder made of sugared hazelnuts and a bit of orange flower water, both of these ingredients adding the almond or nut element to the mirliton filling, which will soon become one defining ingredient of these tartlets. He, as is now the tradition, lines tiny, fluted tartlet molds with puff pastry and ends by dusting the prepared and filled tartlets with fine sugar before baking, giving the mirlitons that fine crispy crust.

Carême goes on to offer recipes for mirlitons aux avelines (a variety of almonds), mirlitons aux pistaches (with the addition of finely ground pistachios and chopped cédrat or citron), mirlitons aux amandes, and mirlitons au zeste de citron or orange. He notes at the end of this short chapter that mirlitons can also be made with chocolate blended with crushed macarons.

In his 1836 Le Pâtissier National et Universel, M. Belon, pastry chef for Monseigneur le Cardinal C, begins with mirlitons ordinaires, a base recipe using crushed macarons and vanilla, sugar, melted butter, into which are folded 4 or 5 egg whites beaten until firm. He then offers coffee, pistachio, and chocolate variations to his tiny tartlets.

Not only does Pierre Lacam offer recipes for mirlitons de Rouen, mirlitons de Toulouse (an almondy cream filling atop apricot jam in a plain sweet pastry), and mirlitons anglais (iced apple tartlets with a cherry on top) in his 1865 Le Nouveau Pâtissier-Glacier Français et Étranger, but he introduces us to moules à mirlitons, the term now used for the small, individual, fluted tartlet molds or pans; he recommends using them for quite a number of his cakes and tarts.

By 1873, it seems that the formula for what is now accepted as the mirliton is pretty set. Jules Gouffé refers to his base recipe as appareil à mirliton, the mirliton batter, in Le Livre de Pâtisserie. And it is most definitely flavored with almond using crushed bitter almond macarons, and now suggesting the use of cream rather than butter, although butter was also acceptable. Gouffé’s first recipe using this mirliton batter is for, tellingly, mirlitons à l’ancienne aux amandes amers. À l’ancienne, as if the mirliton is an old, traditional recipe, only 60 years after it was first mentioned in a culinary book.

And by now, it is clear that making these tiny, individual tartlets was actually a way to use up leftover puff pastry scraps, quite often mentioned in recipes in quite a number of cookbooks.

Interestingly, both Jules Gouffé and Gustave Carlin in his 1887 Le Cuisinier Moderne, have recipes for both types of mirlitons, the filled cigarette- or flute-shaped cookies and the tartlets. Garlin’s flute-shaped mirlitons are referred to as mirlitons de Saint Cloud (a small city on the edge of Paris) and mirlitons français, while his mirlitons suisses are the small tartlets. Now I wonder if there is a connection to the Swiss pastry chef M. Thomas mentioned by Grimod de La Reynière in his Almanach des Gourmands (“In the Rue de Grammont, there is a Swiss pastry chef who, it is said, makes some of his country's small cakes very well.") Could this version of the mirliton originally be a specialty of Switzerland?

Mirlitons of Rouen, Paris, Suisse, Toulouse, Saint Cloud, Nice, chocolate mirlitons, almond, pistachio, citron, coffee…. It’s never ending, but as Pierre Lacam exclaimed, mirlitons are the “gâteau de table” par excellence, “and,” he continues, “it's not unusual for a customer to do as they do in Toulouse with millassons, eating up to twelve, for example…” Even as Sophie Wattel warns that mirlitons are “entremets difficult to manage for weak stomachs” (Les Cent Mille Recettes de la Bonne Cuisinière Bourgeoise à la Ville et à la Campagne, 1886).

Mirlitons - Almond Jam Tartlets

My mirlitons are so simple to execute yet big in both flavor and satisfaction. I simplify the original recipe by using my own sweet pastry crust. The ground almonds or hazelnuts, as you please, create a dense yet tender filling. And I add a scant teaspoon of jam to each tartlet - apricot is traditional, but use your favorite.

1 recipe Sweet Pastry Crust (below)

Mirliton filling

1 cup (3 ounces / 90 grams) ground almonds or hazelnuts

½ cup + 2 tablespoons (4.2 ounces / 120 grams) sugar

2 large eggs

¼ teaspoon vanilla

Scant ⅓ cup (70 ml) heavy, full fat or half fat cream

Jam of your choice (approximately 12 teaspoons)

Sweet Pastry Crust

1 ¼ cups (170 grams) flour

¼ cup (50 grams) sugar

½ teaspoon baking powder

¼ cup finely ground almonds, hazelnuts

7 tablespoons (100 grams) unsalted butter,

cubed

1 egg, lightly beaten

Combine flour, sugar, and baking powder in a mixing bowl. If adding the finely ground nuts, add it to the dry ingredients now, as well. Using only your thumbs and fingertips, rub the butter cubes into the flour until the consistency of damp sand and there are no more large chunks of butter. With a fork, vigorously stir in the lightly beaten egg until all the dry ingredients are moistened and a dough starts to form.

Scrape and gather the dough together into a ball and place on a well-floured surface. Using the heel of one hand, lightly but firmly smear the dough little by little away from you in quick strokes to blend in the rest of the butter.

Scrape up the dough together, re-flour the surface lightly and work/knead very briefly and quickly just until you have a smooth, homogenous dough.

Wrap the dough in plastic wrap and refrigerate for only about 10 or 15 minutes until it is firm enough to roll out easily without sticking to your work surface or rolling pin.

Roll out to approximately ⅛-inch thickness. Line lightly buttered tartlet shells – I lined 12 tiny, shallow 2 ¼ inch wide molds (in something like a cupcake or muffin top tin) + 6 individual 2 ¾ inch wide tartlet molds for 18 tartlets in two sizes - I just use the tins or molds I have. Chill in the refrigerator while the oven preheats and the filling is prepared.

Preheat the oven to 350°F (180°C).

Whisk together the ground almonds and the sugar. In a small bowl, whisk the eggs until thoroughly blended, then whisk them into the almonds and sugar until the mixture is well-blended, thick and smooth. Whisk in the vanilla and the cream until smooth.

Remove the pastry shells from the refrigerator. Place a dollop – ¾ to 1 teaspoon depending upon the size of the tartlet molds you use – of jam in the center of each pastry shell. Carefully spoon or pour just enough of the batter around the jam to fill the shells up ¾ of the way.

Bake for approximately 20 minutes or until each tartlet is puffed slightly, set and a light golden in color.

Remove from the oven, gently remove the tartlets from the tins or the molds and allow to cool on racks before serving. Serve warm or at room temperature.

Thank you for subscribing to Life’s a Feast by Jamie Schler where I share my recipes, mostly French traditional recipes, with their amusing origins, history, and anecdotes. I’m so glad that you’re here. You can support my work by sharing the link to my Substack with your friends, family, and your social media followers. If you would like to see my other book projects in the making, read my other essays, and participate in the discussions, please upgrade to a paid subscription.

We all get to benefit from your research. Not a distraction but a destination. .

What spectacular fun!! I stopped cooking professionally more than 35 years ago. My stints in Paris, were punctuated by hours spent at Shakespeare and Company on QdlaTournelle reading as many old cookbooks as I could. My brandade de morue dates from 1630s and is still a staple in my repertoire. Sadly my pastry chops are null, so your scholarly essay is reads as delicious as your recipe.