“We no longer make tourtes for an entrée…this pastry is no longer luxurious enough to appear on our most opulent tables for the simple reason that its appearance is too vulgar; even the bourgeois class scorns it and now only eat “pâtés chauds” and vol-au-vent; whereas the merchants of old feasted upon tourtes…” - Antonin Carême

Antonin Carême, renowned chef for such illustrious figures as Napoleon’s chief diplomat, Minister for Europe and Foreign Affairs Charles-Maurice Talleyrand, England’s Prince Regent, the future George IV, and Russia’s Tsar Alexander I, the man who single-handedly modernized French cuisine in the late 18th/early 19th century, was a harsh critic of the humble tourte, even as he offered a multitude of recipes for them in the cookbooks he wrote for the instruction of fellow professionals. This brilliant pâtissier was nicknamed, even in his own lifetime, “the chef of kings, the king of chefs”, yet what I love most about him was his snark; dispersed among the pages and recipes of his cookbooks, his abrasive jabs aimed at the British, the classe bourgeoise, fellow chefs, and a multitude of others, were cloaked in the delicate yet self-important guidance of an artisan who unequivocally embraced his superstar reputation. I am sure that in his statement in regards to the tourte he was not only disparaging this savory pastry but he was also dissing the new classe bourgeoise, reminding them, a bit tongue in cheek, of their “common” origins in a not so subtle way, for those eminent upper middle class members of society were not so very long before simple, humble merchants who were quite happy to feast on a “vulgar” meat pie.

Savory tourtes and tarts - separated merely by the addition of a top crust for the former - seem to be such modern fare and yet they are as old as the hills, or at least as old as sophisticated cooking, already a popular dish in Ancient Mesopotamia and Rome. Roman statesman, historian, and philosopher Cato offered a recipe for a tourte or galette, oddly called a placenta, in his treatise De Agri Cultura or De Re Rustic written about 160 BCE, a cheese tourte or cake sweetened with honey baked in a pastry crust or base, resembling the Roman libum, a pastry made of cheese, eggs, and honey in a rye-flour crust baked to serve as a sacrificial treat for the gods. Apicius (whose life spanned from approximately 25 BCE to 37 CE), wealthy epicurean, a grand amateur of sensual, most notably gastronomic, pleasures, who is responsible for a massive collection of recipes published in the 5th century called De re culinaria or De re coquinaria, gave quite a number of recipes using a moule à tarte or tart dish.

The word tourte most likely comes from tortus, latin for “turning in circles” which may very well have been a general way of referring to anything round. Tarte - tart - a term actually not used until the 12th century, is considered a variation of tourte, from the Latin torta, referring to a round cake, the same base as torta panis or round bread.

From its earliest days through the Middle Ages, both the tourte and the tarte were, on the whole, savory preparations, a filling of meats, fish or seafood, vegetables, or cheese in pastry, either a single or double crust. Le Liber de coquina, a cookbook written anonymously at the beginning of the 14th Century for the royal House of Anjou-Sicily, and one of the earliest medieval cookbooks, contains one of the oldest recipe for a tourte, la torta parmigiana, a veritable orgy of hams, sausages, a variety of birds, fresh herbs and saffron, and lots of grated cheese… all in a pastry crust.

Le ménagier de Paris, traité de morale et d'économie domestique, written around 1393 by a young Parisian bourgeois gentlemen “as instruction for his bride on how to cook and run a household” - modern mansplaining, if you will - has a beautiful recipe for une tourte au fromage, a cheese tourte - or tartre - using 2 types of cheeses, one soft, one medium-hard, lots of chopped fresh herbs and greens, and eggs, with the option to add freshly grated ginger. It seems this tart is a single-crust, without a second pastry round covering the filling. To be eaten hot.

During this period, while tourtes and tarts were generally savory, chefs during the Middle Ages, and of course I’m referring to chefs of wealthy households who could afford a panoply of ingredients that the peasants could not, added sweet items like dried fruits, berries, and honey to meat dishes, along with spices and fresh herbs, creating a crossover between savory and sweet pies.

Antoine Furetière added a short definition of tourte to his 1690 Dictionnaire universel contenant generalement tous les mots françois (sic) - Universal Dictionary containing generally all the words in the French language - pâtisserie qui sert aux entrées, aux desserts, à l'entremets, qui est faites de pigeonneaux, des béatilles, de moelle, de confitures, &c. Ce mot vient du latin torta. - pastries serving as starter courses, desserts, entremets (small dishes served between courses, either savory or sweet), that are made with young pigeons, béatilles (small things such as sweetbreads, rooster’s combs, tiny birds, truffles, etc), marrow, jams, etc. This word comes from the Latin torta. Furetière’s tarte is a sweet confection - served at weddings, baptisms, and bourgeois celebrations (this cracks me up) - made with cream, jam fillings, marzipan, or apples.

Apparently not everyone in haute société agreed with Carême that the tourte had gone out of style.

By 1907, Henri Babinski, engineer and gastronome, writing under the alias Ali-Bab, confirmed in his astonishing and well-regarded 5000-recipe tome Gastronomie Pratique that the not-so-humble tourte had been confirmed as a must on all tables. “Tourtes”, he explains, “precursors of the vol-au-vent (individual rounds of puff pastry baked until puffed up tall, filled with a savory, usually creamy filling), are shallow crusts whose filling can be made up of seasoned ground meat, stew, a veal and beef kidney stuffing, quenelles (a fine mixture of fish or meat, breadcrumbs, eggs, shaped and poached), fish, foie gras, mushrooms, etc.” Luxurious, indeed. Take that, Carême! “Originally,” he continues, tourtes were encased in bread dough. “Today, we make them with a shortcrust…with or without a top crust, or in puff pastry with a top crust.”

Let’s get back to our earliest tourtes. While meat tourtes were wildly popular, so were cheese tourtes. It’s no wonder Cato was baking a cheese filling in a crust way back in 160 BCE; cheesemaking is as old as the domestication of animals itself: from milk to cheese, and even to fresh, creamy, tangy yogurt and fromage blanc or fromage frais, is one simple easy step…and several hours in the stomach of a young animal or a sheepskin sack, for the latter treats. While the first known written recipe for cheese dates to the year 60 AD by Columelle, a Roman agronomist - by this time cheese was a basic food item in Ancient Roman - the first traces of cheese date back some 7,000 years in Poland. Apparently, cheese, or at least cheesemaking skills, arrived in France at about the same time. By the time Pliny the Elder published Natural History in 77 AD, a variety of cheeses, according to his documentation, were being produced all around what is now France. Julius Caesar was known to have enjoyed a particular blue cheese produced in the French region of Aveyron, later famous for Roquefort. Charlemagne was offered a blue-veined cheese 8 centuries later not far from where Caesar ate his salty bleu.

A tourte made with cheese, and blue cheese was a flavorful choice, fromage frais or thick yogurt, and eggs, was a familiar dish on medieval tables. I’ve recreated a recipe that is extremely easy, only a few ingredients, turning out a savory tart whose flavor surpassed even my own expectations. No wonder it has been popular for centuries. Truly a treat worthy of the gods.

Tourte au fromage

For 6 x 4 ½-inch (11 cm) individual tarts or 1 x 10-inch (25 cm) tart

10 ½ ounces (300 grams) all-butter puff pastry (good quality store-bought is great)

3 ½ or 4 ounces (about 100 grams) blue cheese such as Roquefort

4 eggs

½ cup (125 ml) heavy cream

½ cup (125 ml) fromage frais or thick Greek yogurt

Salt and freshly ground black pepper

Pinch nutmeg, about ⅛ teaspoon

Preheat the oven to 375°F (190°C). Have ready a baking sheet large enough to hold 6 tartlet molds with a comfortable space around each, if making the individual tarts.

If using store-bought puff pastry, simply unroll the fresh dough - I carefully lifted the dough up from the parchment paper the dough comes rolled in and rubbed a small amount of flour between the paper and the dough so the bottom of the dough is lightly floured. If using homemade, gently roll out the dough to approximately ⅛-inch or so (3 mm) thickness on a lightly floured surface.

Line the 6 tart molds, gently lifting and pressing into each mold so as to carefully line the bottom and sides well into the corners without the dough ripping. Press the dough into the molds and slice off the dough even with the top edge. Place the lined molds on the baking sheet.

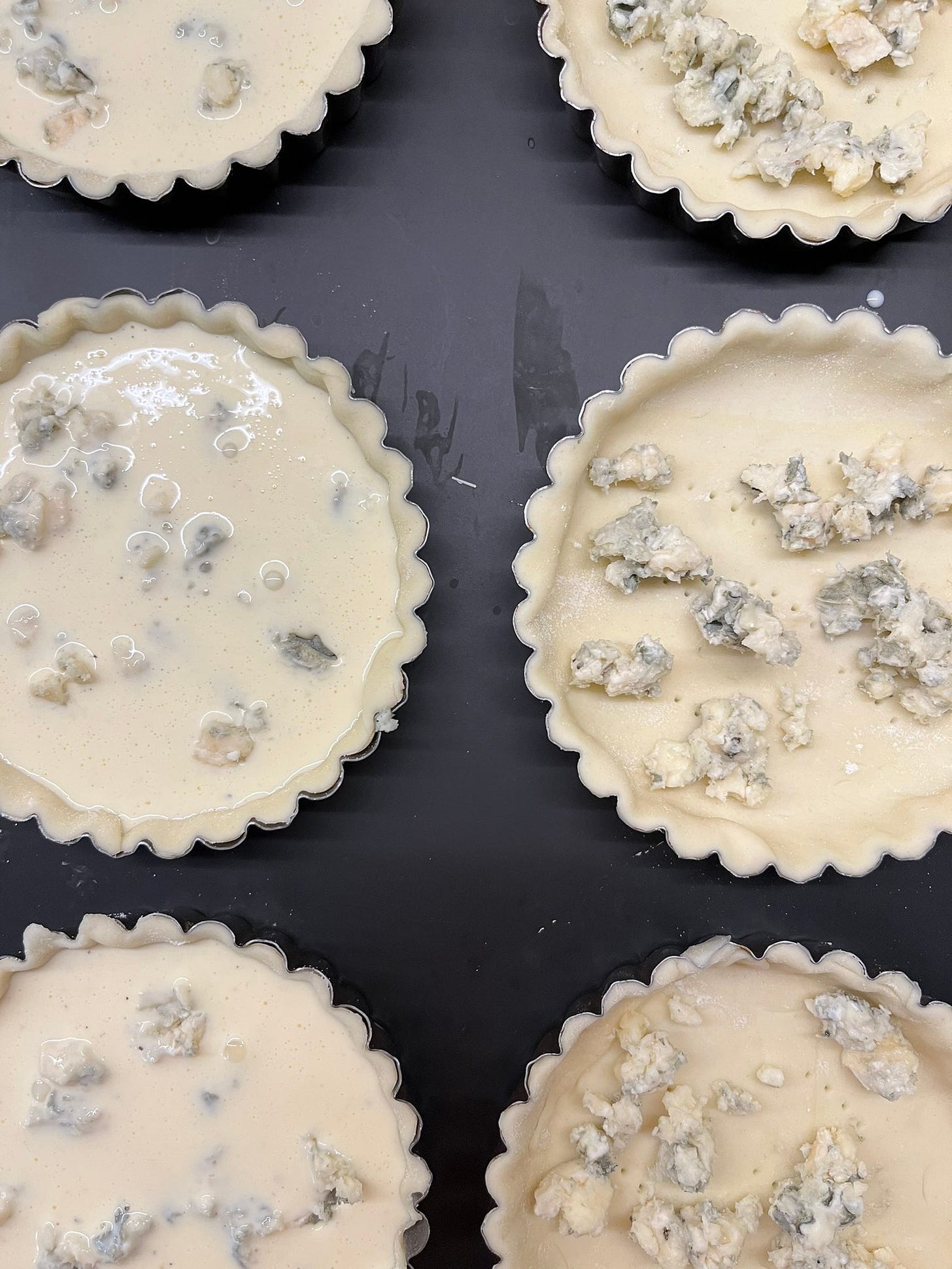

Coarsely chop or break up the cheese - it will be sticky - and evenly divide among the tart molds.

In a medium-to-large mixing bowl, whisk the eggs to blend well. Whisk in the heavy cream and the fromage frais or Greek yogurt until well blended and smooth. Add salt - not too much as the blue cheese is salty - a generous grind of black pepper, and a pinch of nutmeg then whisk to blend well.

Evenly divide the cream mixture among the tart molds over the blue cheese; the filling will probably come to the edge of the molds.

Place the baking tray into the preheated oven and bake for 40 to 45 minutes until the tarts are puffed and deeply golden. The crust should be golden as well.

Remove from the oven and allow a few minutes for the tarts to cool slightly; they will settle and become less puffed up.

Serve hot or warm with a salad. Any uneaten tarts should be wrapped and refrigerated then can be gently reheated before eating.

Thank you for subscribing to my Substack, Life’s a Feast by Jamie Schler, where I share my recipes, mostly French traditional recipes, with their amusing origins and history. I’m so glad that you’re here. You can support my work by sharing the link to my Substack with your friends, family, and your social media followers. If you would like to see my other book projects in the making, read my other essays, and participate in the discussions, please upgrade to a paid subscription.

It's always been curious to me that food goes in and out of fashion. These look amazing and if I can get my hands on some all-butter puff pastry (it is oddly hard to find around here) I will put them on my list to make. Cheese and pastry is always in fashion around here!

You made my day! What an honor to be dubbed “the chef of kings, the king of chefs” sounds better than being royalty to me! And your mention of the Parisian bourgeois throwing in modern mansplaining made me crack up, so true!! Also I had no idea the first traces of cheese date back to 7000 years ago in Poland, sooo fascinating!