Above all, keep it simple. - Auguste Escoffier

The 1952 cookbook Cuisine Express (meals for busy people) by Mrs. M. S. Sémarque has a recipe for a Quatre-Quarts that embodies the type of everyday pastry that is prepared in the typical French home:

"Quatre-Quarts (1 h.) 4 eggs - the same weight sugar, flour, and butter - lemon zest : Work the butter, sugar, and whole eggs together. Add the flour, then the lemon zest; work the batter a bit. Pour into a buttered cake pan (filled three-quarters). Bake in a moderate oven for about three-quarters an hour. Allow to cool before removing from the pan.”

Plain, simple, and quick.

Forget those fancy pastries one finds in every pâtisserie and boulangerie across France, layers of puff pastry, delicate choux, creams, and ganaches. And forget lengthy instructions. The baking one does at home is, almost without fail, plain, simple, quick, and, more often than not, economical. Apple cake, far breton, maybe a clafoutis or flognarde in season, a simple tart of pâte sablée with fruit pressed into the dough, sprinkled with sugar, and baked. And the humble quatre-quarts.

Quatre-quarts. The name - meaning four-quarters - comes from the fact that the cake contains four main ingredients (flour, sugar, butter, eggs) in equal quantities by weight, therefore each representing a quarter of the cake. In other words, a quatre-quarts is the French pound cake, which is composed of 4 quarters, each quarter being one of 4 ingredients.

The origin of the quatre-quarts - or the pound cake - is murky at best, with food writers pointing to somewhere in northern Europe around the year 1700, and becoming a French specialty sometime in the 18th century, neither of which I could find trace of or confirm. All that really is known is that the first written mention of and recipe for a pound cake was in the first American cookbook, American Cookery, written by Amelia Simmons in 1796. And her recipe was simple indeed, writing only "one pound sugar, one pound butter, one pound flour, ten eggs, rose water one gill, spices to your taste; watch it well, it will bake in a flow oven in 15 minutes.”

In 1851, Eliza Leslie includes a much more extensive and detailed recipe for a pound cake in her book Direction for Cookery. Evidently, she wasn’t really taken with the simple pound cake, for she adds cinnamon, mace, nutmeg, white wine, brandy, rose water, and lemon oil to her pound of flour, pound of sugar, pound of butter, and ten eggs. She then suggests icing the cake and that the cake “will be very delicate if made with a pound of rice flour instead of wheat.” But she makes it quite clear earlier in her book “Common pound cakes are now very much out of use. They are considered old-fashioned.” Well.

It’s possible that the first mention of the pound cake in French was in Le Cuisinier Anglais, traduit en français, avec le titre de chaque recette en français et en anglais (The English Cook, translated into French, with the title of each recipe in French and English) published in Paris in 1821. The cake was named, aptly, gâteau à la livre, quite literally pound cake (or cake by the pound) and was composed of a pound each of flour, butter, sugar, and eggs (10 yolks + 5 whites); the cake was flavored with “a little nutmeg” and “a little eau-de-vie” and after beating together "for one hour” (one hour!), 1 pound Corinth raisins or 1 ounce caraway seeds was added.

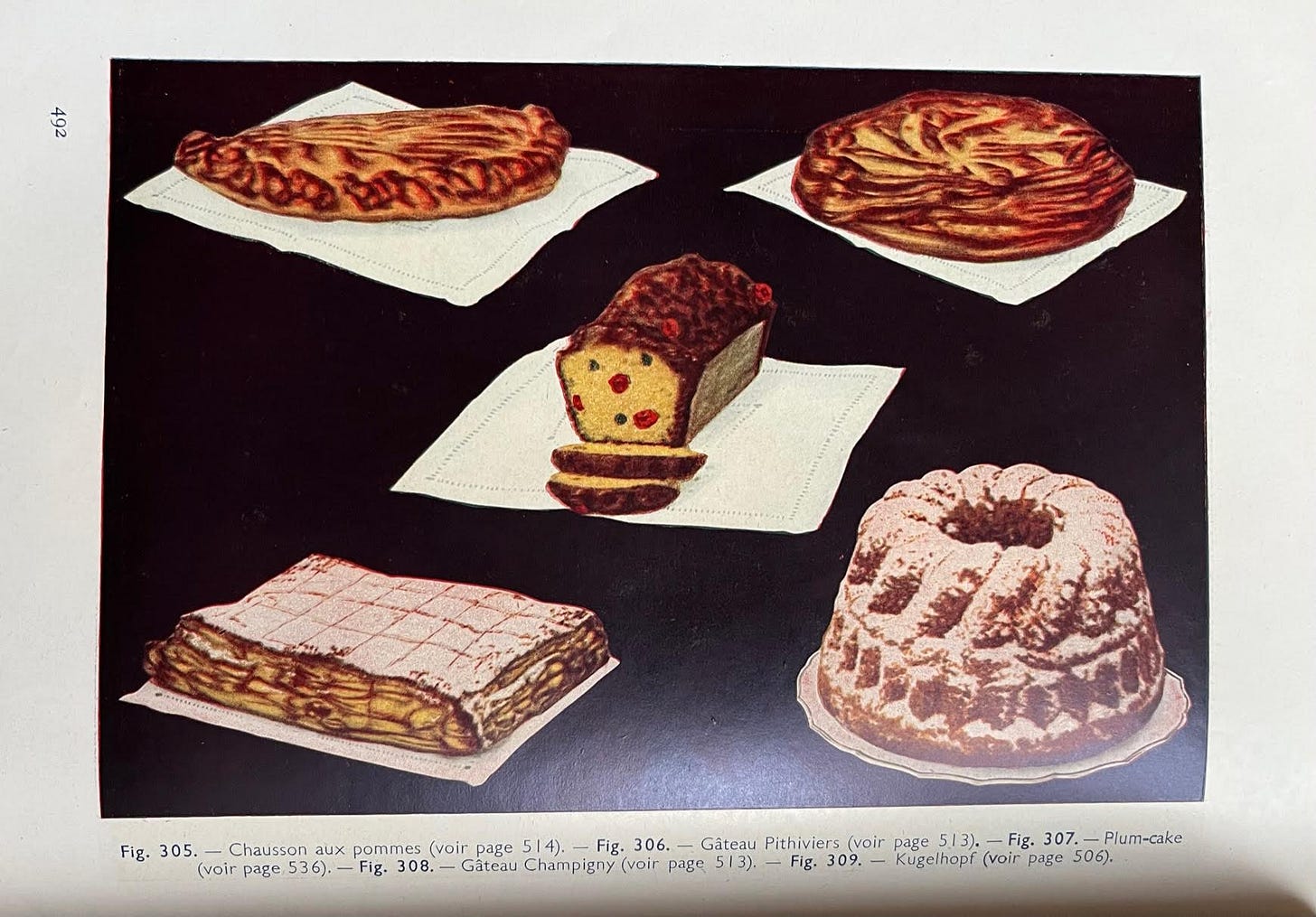

We actually don’t see a cake called a quatre-quarts (or, for that matter, another gâteau à la livre) in a French cookbook until the the beginning of the 20th century. Before this, a similar cake referred to as plum-cake popped up here and there, another take on another English cake, with the same proportion of ingredients - a pound each butter, sugar, flour, and eggs, but with the addition of a ton of raisins and dried candied peel, very English, often macerated in rum. Sometimes the quantity of flour is increased, sometimes it’s in equal proportion to the other ingredients. We see recipes for plum-cake in books throughout the second half of the 19th century and into the early part of the 20th (although for some odd reason plum-pudding seems to have been more popular), from Pierre Lacam’s 1865 Le nouveau pâtissier-glacier français et étranger, Jules Gouffé’s 1873 Le Livre de Pâtisserie, la cuisinière de la campagne et de la ville, or Nouvelle Cuisine économique by L.E. Audot from 1896, to Émile Darenne and Émile Duval’s 1909 Traité de pâtisserie moderne. Urbain Dubois’ 1896 Grand Livre des Pâtissiers et des Confiseurs has a recipe for plum-cake listed as a pâte à plomquet… plum-cake now written as the Frenchman would have pronounced it: plomquet. His recipe contained 500 grams of each of the 4 ingredients.

Pierre Lacam finally begins to clarify things for the French by including recipes for both a Plum-cake anglais and a Plum-cake français in his Le Mémorial Historique et Géographique de la Patisserie in 1900. The English plum-cake is made with 500 grams butter and sugar each, from 7 to 16 eggs per pound (so, I imagine, 500 grams eggs), but 625 grams flour. The French plum-cake is made with 250 grams each of the sugar, butter, eggs (6), and flour, as well as a fraction of the candied fruit (60 grams to the English plum-cake’s 500 grams raisins and 125 grams candied peel along with some rum or lemon). Darenne and Duval do the same in their book 9 years later with their two recipes plum-cake n° 1 and plum-cake n°2 (very Dr. Seuss, right?), while also offering n°3 and n°4 variations, plum-cake Russe and plum-cake ordinaire by slightly changing the quantities of each of the same ingredients.

But the French are slowly moving away from the English plum-cake and closer to the French quatre-quarts. The earliest, as far as my research can attest to, a recipe for a gâteau quatre-quarts appears in a cookbook is 1906, in L’Art du Bien Manger (The Art of Good Eating) curated with “practical formulas for preparing famous dishes from top restaurants and master chefs at home,” a book specifically written for the home cook, not professional chefs. And the instructions couldn’t be clearer: “Weigh 4 eggs, then weigh as much flour, as much sugar, and as much butter.”

The French quatre-quarts is finally, officially born.

But this cake, today so emblematic of French home baking, didn’t really take off until 20 years or so later when it seems to just suddenly appear regularly in cookbooks. The first I could find, other than L’Art du Bien Manger, that included a recipe for a gâteau quatre-quarts was Tourtes Tartes Pâtisseries mets sucrés by Mme. F. Nietlispach in 1930. In fact, the author includes recipes for both a gâteau quatre-quarts and a plum-cake, her recipes differing only slightly from each other:

Gâteau Quatre-Quarts : 200 grams sugar, 200 grams flour, 200 grams ground almonds, 4 eggs, 200 grams butter; half the batter is poured into the buttered cake pan then a layer of jam is spread on this layer of batter before adding the rest of the batter.

Plum-Cake : ½ pound each butter, sugar, and flour with 1 packet baking powder, 6 - 8 eggs, ½ glass rum, 10 grams ground almonds, chopped candied orange and lemon peels, raisins both sultanas and corinth.

In 1932, La Cuisine Familiale (manger mieux, dépenser moins: eat better, spend less) includes only a recipe for gâteau quatre-quarts, a cake that includes “4 eggs, same weight in flour, sugar, and butter; 1 spoon of eau-de-vie, 1 spoon orange flower water.”

And the recipe for the quatre-quarts is now firmly established.

For a short while longer, the plum-cake and the quatre-quarts do still continue to make their appearance side-by-side in several cookbooks of the era, from Henri-Paul Pellaprat’s (founder alongside Marthe Distel of the esteemed École du Cordon Bleu and today considered the father of modern French cooking) 1937 Les Desserts (Pâtisserie et Entremets) to La Pâtisserie de Marie-Claire by Jeanne Grillet in 1948. Both of these authors differentiate these two cakes by now putting chopped candied fruit and rum only in the plum-cake, while Mme. Grillet flavors her quatre-quarts with a bit of lemon and M. Pellaprat his with (finally) vanilla. They both also explain that a quatre-quarts recipe is the same one uses to make madeleines, only baked in one single cake pan.

And Pellaprat also seems to be the first to finally add baking powder to his quatre-quarts.

"The greatest dishes are very simple.” Auguste Escoffier’s words are always taken to heart in the French kitchen, and, unlike the cookbooks aimed at professional chefs, the quatre-quarts has always been found exclusively in cookbooks written for the home cook, la cuisine familial. But simplicity only works when the ingredients are of good, if not the best, quality. A cake as simple as a quatre-quarts is only as good, as tasty, as the quality of the eggs and butter, and, of course, the flour and sugar that go into it. As M. Pellaprat writes at the opening of his cookbook La Cuisine Familiale: “Cooking is like anything else: no matter how simple you want it to be, simplicity must not exclude quality, and it's just as easy and no more expensive to do it well than to do it badly.”

Nothing defines and exemplifies French family home baking than these 2 extremely simple cakes. With a few basic ingredients and a few minutes, each cake is in the oven and baking. And each cake is satisfyingly dense (toothsome!) yet moist and tender, and, despite the limited number of ingredients, is fragrant and flavorful. Only one rule: follow the instructions carefully on weighing or measuring out the ingredients so each of the 2 cakes comes out perfect.

Quatre-Quarts

For this classic recipe, you need a digital kitchen scale that weighs in grams.

4 large eggs, the yolks and whites (the eggs without the shells) should weigh approximately 250 grams

250 grams unsalted butter, softened

250 grams sugar

1 or 2 teaspoons vanilla extract or fine zest of 1 lemon

250 grams flour

2 teaspoons baking powder

Preheat the oven to 350°F (180°C). Butter a regular loaf pan; I line the bottom of the pan with a fitted strip of ovenproof parchment paper.

Break the 4 large eggs into a bowl that has been set on a digital scale set to grams. The eggs should weigh approximately 250 grams.

Put the softened butter in a large mixing bowl with the sugar and beat until creamy.

Beat in the eggs one at a time; beat in the vanilla or lemon zest with the last egg.

Stir the baking powder into the flour; beat the flour into the batter little by little in several additions to avoid lumps. The batter should be smooth and creamy.

Scrape the batter into the prepared pan and bake in the preheated oven for approximately 60 minutes until the cake is set in the center.

Remove from the oven and allow to cool for several minutes before turning out of the cake pan and cooling completely on a rack.

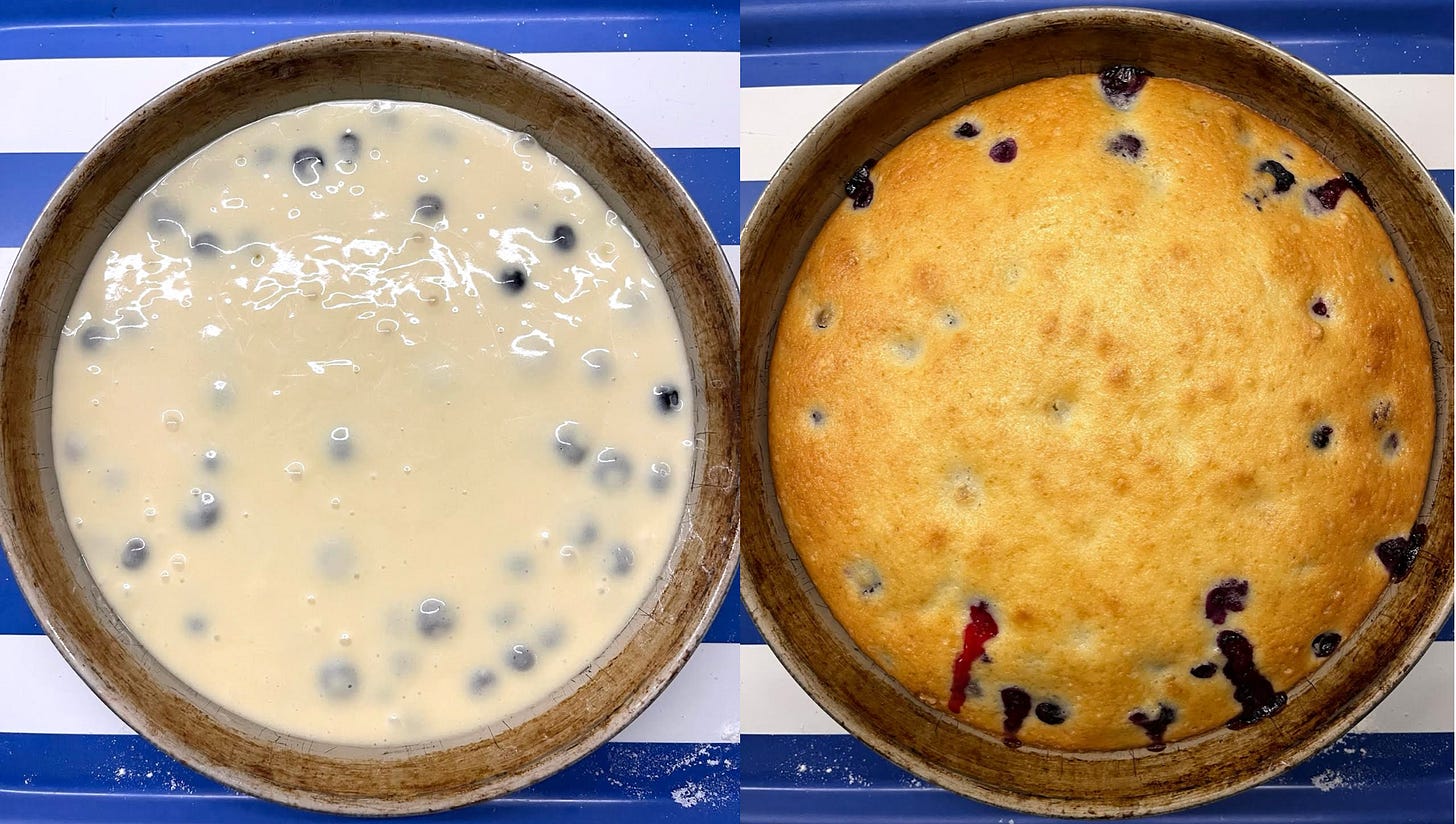

Simple Yogurt Cake with blueberries

IMPORTANT: this recipe uses the cleaned and dried yogurt pot as the unit of measure and it is important you do the same: DO NOT WEIGH THE INGREDIENTS.

This is such an excellent example of the way the French often bake at home… in fact, many old cookbooks are written this way with odd units of measure. I find it charming (even if I long thought it crazy). It makes a very simple recipe even simpler. And this dense (almost chewy) but tender, moist, delicately sweetened cake - my addition is the berries - is an excellent example of the kind of homemade snacks you will find in any French home.

1 small pot - @ 125 or 140 grams - plain/unsweetened yogurt

2 pots sugar

3 eggs

3 pots all-purpose flour

1 teaspoon baking powder

¼ teaspoon salt

½ pot vegetable oil (eyeball it)

1 teaspoon vanilla extract, optional

Blueberries; optional but excellent

Preheat the oven to 350°F (180°C).

Oil the bottom and sides of a 9-inch (23-cm) cake pan; oil the pan with a paper towel, soaking up the excess. Line the bottom of the pan with a round of parchment paper.

Pour/spoon the yogurt into a large mixing bowl. Wash and dry the pot the yogurt came in as this will be your measuring cup.

Measure out the 2 pots of sugar (fill and level the top with a flat blade) and pour over the yogurt in the bowl; whisk well until completely blended, smooth and creamy.

Add the eggs to the yogurt/sugar one at a time, whisking in well after each addition.

Measure out the 3 pots of flour (lightly spoon into the pot until mounded then level the top with a flat blade) into a small bowl. Add the baking powder and salt to the flour; stir just to blend.

Measure ½ a yogurt pot of oil and pour into the mixing bowl with the yogurt and sugar and whisk to blend. If adding vanilla, add it in with the oil.

Add the dry ingredients to the mixing bowl in 3 or 4 additions, whisking really well after each addition to avoid lumps. The batter should be smooth and creamy.

Fold in the berries.

Scrape the batter into the prepared pan and bake in the preheated oven until set through and barely beginning to pull away from the sides of the pan, about 30 minutes or a bit more.

Cool and eat.

Thank you for subscribing to Life’s a Feast by Jamie Schler where I share my recipes, mostly French traditional recipes, with their amusing origins, history, and anecdotes. I’m so glad that you’re here. You can support my work by sharing the link to my Substack with your friends, family, and your social media followers. If you would like to see my other book projects in the making, read my other essays, and participate in the discussions, please upgrade to a paid subscription.

Now do a kilo cake, please.

I am so very impressed by the research that goes into these posts! I hope they will be a book one day...