You share your heart like a king's cake. And so great is your art, lovable daughter of Eve, that each one believes herself to be the sole owner of the bean. - Maurice Donnay

Each year, I celebrate Epiphany with a traditional galette des rois - well, I don’t celebrate the holiday but I certainly celebrate the month of January when bakeries around France are abundant, absolutely overflowing with galettes, creamy almond frangipane or sweet apple or pear purée or vanilla-infused pastry cream encased in golden, flakey puff pastry in which is nestled a ceramic charm. And always accompanied by a shiny gold paper crown. I have written about the galette des rois and its very long history, offering my own recipe with the choice of 3 fillings, a recipe I use most years when making my own. But as the season is once again upon us, I decided that I would make a gâteau des rois - also called a brioche or a couronne des rois - the traditional Epiphany confection in France’s Provence.

We already know that the tradition of serving a king’s cake is rooted in Roman times and the pagan Saturnalias festivities coinciding with the Winter Solstice:

As early as Roman times, the tradition of naming a “king for the day” during the Saturnalias festivities existed. Saturn, considered an angry dethroned king in exile, had to be kept at bay, the disorder of the “evil days of Saturn” thwarted. So a new king was named to take away the power from Saturn. The idea of a “king’s cake” was part of the festivities. Each great family had a banquet during which a cake was cut and served to the entire household, slaves and later servants included. A bean was tucked into the cake, the prize that would designate the king - or more likely the prince, the « Saturnalicius princeps » - from among the slaves, in later ages, from among the servants.

Others say that the origins of the festivities around the Christian Epiphany can be traced back to the celebration of the Dionysus, the god of vines and wine, of festivities and excess. The feast in honor of Dionysus was in mid-winter, coinciding again with the Winter Solstice, a fête that symbolized a seasonal resurrection of the earth with the return of light and thus the rebirth of the vines. In fact, the word Epiphany is rooted in the Greek Ἐπιφάνεια or Epipháneia signifying manifestation or appearance. As early as the 4th century, these festivities began to be associated with the period following the birth of Jesus in the Christian sects of the Orient.

It wasn't until the 13th century that the Church of France appropriated the pagan feast of Saturnalias and began to associate it with Epiphany to celebrate the birth of Jesus and his presentation to the Magi, the 3 Kings.The gâteau des rois arrived in the 14th century with the Popes of Avignon. And along with both the cake and the (rambunctious, often drink-filled) celebration came the tradition of dividing the cake into as many portions as there were guests, plus one slice. This extra slice, called the "part du Bon Dieu" or "part de la Vierge” (the Good Lord’s slice or the Virgin’s slice), was given to a pauper. And, of course, whoever found the bean in his or her slice was crowned king and obliged to offer a round of drinks to his or her fellow revellers.

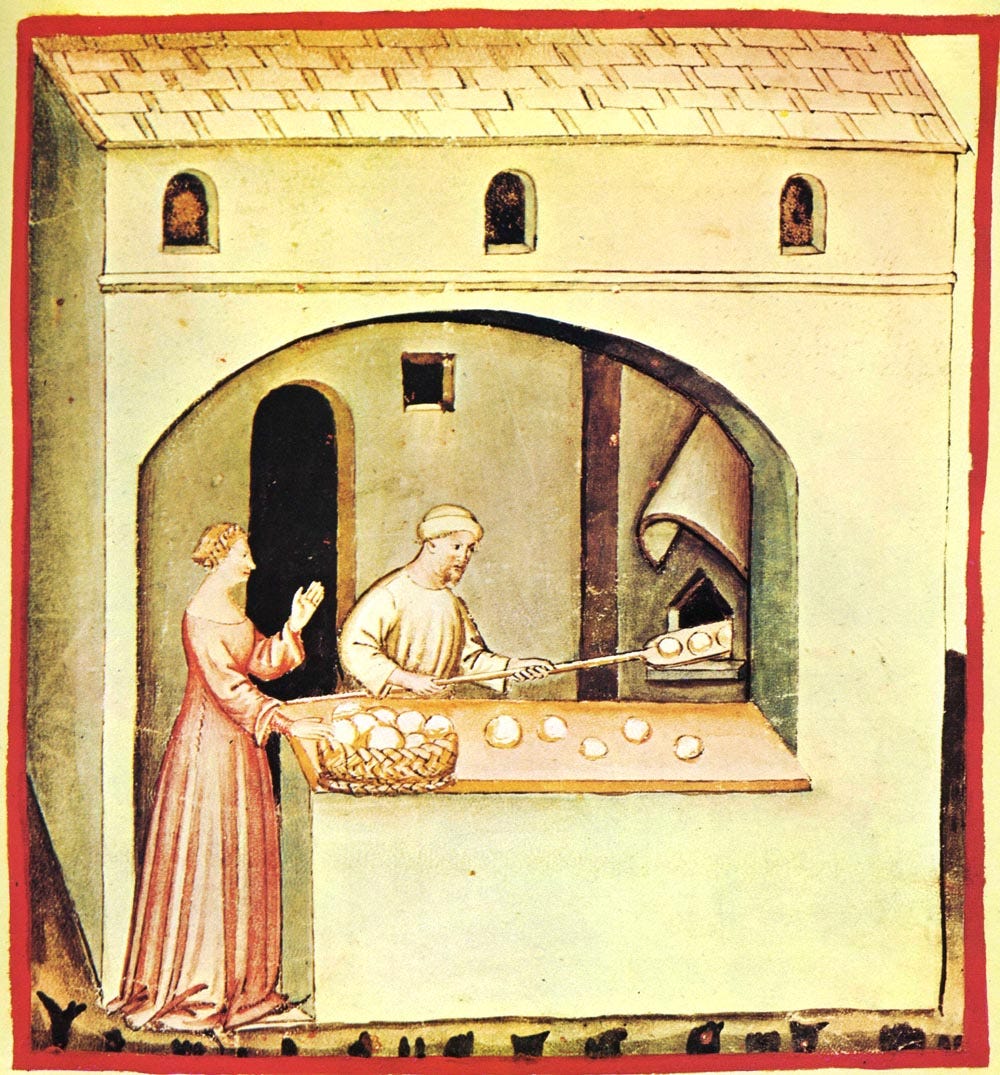

The earliest king’s cake, like the earliest cakes in general, was more than likely a bread sweetened with honey and dried fruits such as figs and dates; we know that puff pastry was a much later invention, the first written mention of pâte feuilletée or pastèz d’Espaigne fueiltéz was in 1604 in L’Ouverture de cuisine by the master chef - maître cuisinier - for the Prince of Liège, Lancelot de Casteau, and the frangipane arrived with Marie de Médicis from Italy in the 16th century, both pushing the creation of the first galette des rois probably much later than that, most likely as late as the 19th century with the galette à la parisienne. So the first cakes were, in fact, bread or, later, what is now known as fougasse, a flat bread. What we think of as cake actually appeared around the 7th century when butter and eggs became more common, and developed even more in the Middle Ages across France with the arrival of cane sugar from the Middle East with the Crusades.

Brioche as we know it, a yeast bread enriched with butter, eggs, and milk, dates back to this period, the 13th and 14th centuries, developing further over the course of the next two centuries. It’s hard to pinpoint when the original king’s cake transformed from bread sweetened with honey and fruits to the more delicate and cake-like brioche, but gradually it did. And, of course, each region, as in all things pastry in France, appropriated the gâteau des rois, recreating the confection in their own image with local flavorings and traditions. The good people of Provence, where the day had traditionally been celebrated with the local fougasse bread (la fougasso di rèi), soon embraced the sweet brioche, perfuming it with orange flower water, and decorating it with sugar and glistening candied fruits. There are 2 explanations for the round crown shape and the decoration of the gâteau des rois: the first is that the circular brioche symbolizes the path of the 3 Wise Men, and the glistening, jewel-like candied fruit the gems or treasures brought to the infant Jesus by the Kings; the other is that the brioche represents the Kings’ crowns and the candied fruit the precious stones in the crowns.

This is a delicate yet moist brioche, light and tender, with a beautiful hint of the orange flower water and the rum. The sugar atop the cake gives it all the sweetness it needs.

Gâteau des Rois

This is really quite a simple pastry to put together and, if you follow the directions and don’t rush the process, it’s also quite foolproof.

Brioche

1 teaspoon sugar

1 tablespoon (10 grams) instant dry yeast

Scant ½ cup (100 ml) milk, warmed

3 cups (420 grams) flour, more for the work surface

4 tablespoons (60 grams) sugar

1 teaspoon salt

1 tablespoon orange flower water

1 tablespoon amber rum

2 eggs, preferably at room temperature, whisked to blend

5 tablespoons (75 grams) unsalted butter, cubed and softened

Glaze and decoration

1 egg yolk

Pinch salt

1 tablespoon milk or cream

Pearl sugar

Candied or glacé fruit (lemon and orange peel, cherries, Angelica, or any fruits in bright, jewel-like colors)

Place 1 teaspoon sugar and the dry yeast in a small bowl; add the warmed milk. Gently stir with a fork just to break up any clumps of yeast and to make sure the yeast is pressed into or under the surface of the milk. Allow the yeast to activate for about 10 minutes or so until dissolved and a little foamy.

Put the flour in a large mixing bowl. Whisk in the sugar and salt just to blend and make a slight well in the center of the dry ingredients. Pour the yeasty milk into the well, scraping the bowl to get it all out. Add the orange flower water, the rum, and the beaten eggs. Using the fingers of one hand, blend the wet ingredients into the dry, stirring until most of the dry ingredients are wet, then folding, turning, and kneading with your fingers for several minutes until the dry ingredients are all damp and starting to come together into a scraggly dough. Scrape the sticky dough off of your fingers and scrape the bowl to get as much into the dough as possible. Continue to knead for a minute or two.

Using just the fingers of one hand, knead in the soft butter a couple of cubes at a time - I smear the butter onto the dough before folding the dough over onto itself to encase the butter then keep kneading and folding a few times before doing the same with a couple more cubes of butter, again and again until all the butter is well folded and completely blended in. Knead for another minute or two until the dough begins to become smooth.

Scrape the dough out onto a very lightly floured work surface and, using one or both hands, knead the dough for 10 to 12 minutes, just smoothing a bit more flour onto the work surface when needed to keep the dough from sticking. At the end of the kneading time, the dough will be beautifully homogenous, smooth, silky, and elastic. Shape lightly into a ball.

Place the ball of dough either back in the same mixing bowl or into a clean mixing bowl (I rub just a little soft butter around the bottom and sides of the bowl to keep the dough from sticking. Cover the bowl with plastic wrap and a clean kitchen towel and allow the dough to rest and rise at room temperature for 3 hours.

At the end of the rise period, scrape the dough onto a very lightly floured work surface then press and knead the dough for just a minute to release the air trapped inside the dough during the rising period. The dough will have become softer and more elastic.

As you knead the dough a bit, place the charm inside the dough.

Shape the ball of dough into a crown by pushing your fingers through the center of the round of dough to make a hole then gently pull and shape until the round of dough is approximately 8 inches (20 cm) diameter with a center hole about 3 1/5 or 4 inches (9 cm or so) diameter.

Carefully place the crown of dough onto a large, parchment-lined baking sheet; reshape if needed. Cover the dough once again and let rise a second time for 1 hour 30 minutes.

Preheat the oven to 350°F (180°C).

Prepare the glaze by blending the egg yolk with a pinch of salt and a tablespoon of cream or milk. Lightly brush the glaze all over the surface of the brioche. Generously cover the brioche with pearl sugar.

Bake in the preheated oven for 25 minutes until the brioche is a beautiful golden brown; the bottom of the brioche should be a uniform golden brown.

Allow to cool on a rack before decorating with candied fruits and serving.

Thank you for subscribing to Life’s a Feast by Jamie Schler where I share my recipes, mostly French traditional recipes, with their amusing origins and history. I’m so glad that you’re here. You can support my work by sharing the link to my Substack with your friends, family, and your social media followers. If you would like to see my other book projects in the making, read my other essays, and participate in the discussions, please upgrade to a paid subscription.

This type of gangster des rois was also served all over the French southwest too. I was studying there back in those non-internet days in the late 1970s, and that was the only galette I knew. I was astonished to discover a whole different kind of galette in the North!

The "bean" was a small round plastic object that was usually a smiling moon, nothing like the plethora of ceramic cartoon & movie characters we can get in galettes today. I used to save them with the paper crown and send them to my French mom who left France in 1957. She enjoyed getting little reminders of her home country in the mail. 🙂❤️

I never made the connection between the galette and Saturn before! I'm much more familiar with the more garish King Cakes of New Orleans with their plastic babies hidden inside, which makes me wonder...Saturn is the Roman version of Cronus, who famously swallowed all his children save one (Zeus) immediately after birth. Cutting him open to find them feels much more Brothers Grimm than mythological. Then again, being slavishly faithful to the original story and employing powerful emetics when serving dessert to one's guests does seem much less appetizing. Happy New Year, Jamie.