It is good food and not fine words that keep me alive. - Molière

I recently posted a question on social media asking my readers what topics they would want me to write about, if there was anything they were curious to know about my life, my hotel, or my town. I received some excellent responses, but one immediately popped out at me: Do you have the impression that the soil flavors the fruit in ways that are unique to your region?

Since we purchased the hotel in 2015, my husband and I have hosted a wine tasting for a large American tour operator during high season. We don’t offer these weekly groups of 28 visitors a classic wine tasting they will get in any cave or domain, one based on smelling, looking, tasting, and describing a closed selection of their own wines. Instead, we explain how wines across France are organized, labeled, sold, purchased, and ordered in shops and in restaurants; we explain the French system of AOC - appellation d'origine contrôlée (controlled designation of origin). The AOC - or, in some cases AOP (appellation d’origine protegée) or ICP (indication géographique protégée) for some products - sets the rules on French wines as well as a multitude of other products, spirits, cheeses, fruits, vegetables, meats, among others.

I myself learned a lot. I’ve been living in France for decades, and writing about food (and shopping for it, buying it, and eating and drinking it), but this really made it completely clear for me. And I realized how many of my fellow Americans weren’t really familiar with this system of food and wine classification.

What does this label AOC mean? Let’s start with the wine.

In the United States, one orders or buys wine by the grape: a Cabernet Franc, a Pinot Noir, a Merlot or a Syrah. Not so in France. In France, wines are ordered by appellation, by a wine’s designated origin.

First and foremost, an appellation or AOC is tied to a geographical location; all of the grapes grown or raised in that geographical location experience and benefit from the same soil, water table/natural irrigation process, weather conditions (rainfall, sunshine, temperature fluctuations), etc, specific to that region. And because certain things thrive better in one region or another, a variety or varieties of grapes, for example, which are then influenced by the combination of these various elements, this becomes a significant factor in the creation of a distinct and unique wine or selection of wines.

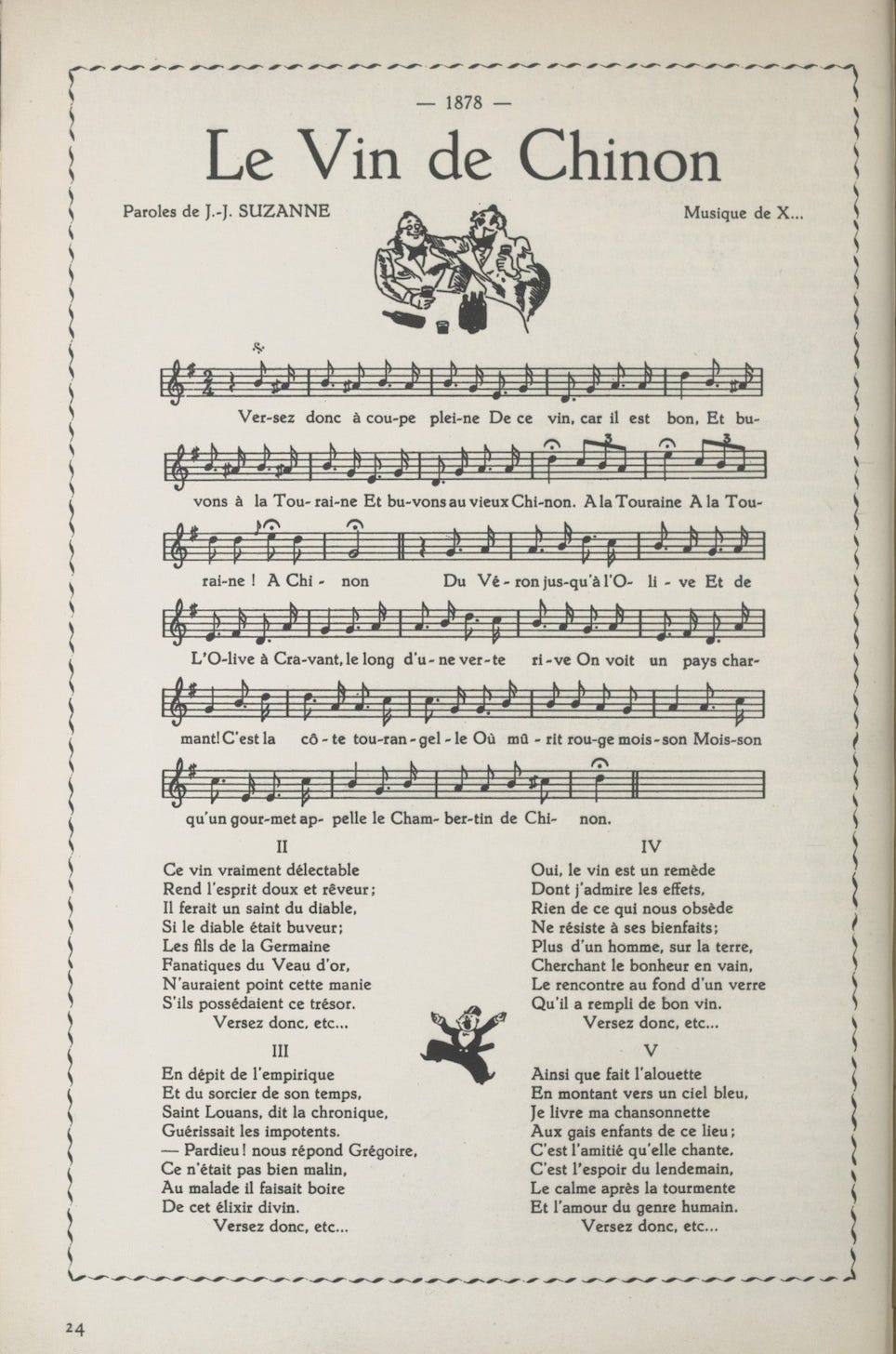

You already know a few appellations without even thinking or realizing that is what they are: Bordeaux, Champagne, Sauternes, Chablis, Muscadet. Well, there are a total of 363 appellations or AOC across the country. Chinon is one of them, and I’ll use this as an example. Chinon is a city, but Chinon is also an appellation comprising 26 towns and villages, from Seuilly and Saint-Germain-sur-Vienne through Chinon itself to Cravant-les-Côteaux. This group of towns and villages, with vines and domains spread over 2,400 hectares, all share the same geographical characteristics and weather peculiarities, together what we call terroir.

But it isn’t only the location and those distinct physical components. Wines produced under the same AOC umbrella share a number of other implied and imposed factors.

These wines—and the people who craft them—are steeped in a rich, collective history of savoir-faire and tradition, inseparably tied to a singular place in France. Savoir-faire and tradition mean that the product is still made the way it has always been made, by hand, under the same conditions, and using the same tools, preparation, and production process, or pretty close to it. And the producers are using the same ingredient or ingredients, grown, raised, fed, harvested or collected in the same ways, or mostly.

This means that all of the wines made from those grapes then produced according to local traditions have similar characteristics, a unique personality, distinct (to the discerning palate, and often the less discerning palate like mine) from all other wines of all other regions and of all other appellations.

And each appellation, each group of producers making wines under that AOC, has a set of imposed rules and regulations specific to that AOC that must be followed in order to be allowed to carry that distinguished label, and distinguished it is. These rules specify which grapes and only which grapes can be used for the wines, where (within the confines of the of the region or not) and how they are planted, maximum yield of grapes that can be grown and used from a plot, how the vines are cut and trained, spaced, and harvested, through production and aging, when, how, and in what style. Chinon reds and rosés must be 100% Cabernet Franc grapes, the whites, dry and still, are 100% Chenin Blanc. And while a producer in Chinon is certainly free to produce something else, a sparkling wine, for example, they can, and they can sell it carrying the name of their domain or winery, but those bottles cannot bear the AOC label Chinon.

To be clear, each producer within that AOC can put his or her own personal mark on that wine by playing with each element. Think of it as music: everyone receives the same score, but each producer plays it as he or she feels, slower, faster, sweeter, harsher, lighter or not, blending the grapes that grow on different plots in different proportions, playing and experimenting with each step of production all along the process.

And because each appellation is connected to, descriptive of a very specific geographical location, the name of that appellation usually comes from the largest city within the defined area.

And why don’t the French order French wines by grape? Not only because of those taste difference between appellations, but because it won’t necessarily be clear what you want. Order a Cabernet Franc and you might be served a red or a rosé, both 100% cab franc. And a Chenin Blanc? Do you want a dry white, a sparkling, or a sweet dessert wine? Yes, that’s it. In fact, many French don’t even know what grape varieties are used for an appellation; and you won’t often find the grape mentioned on the label of a bottle.

Why AOC wines? Lots of regulations, you say? Of course, but seeing that Chinon AOC classification on the label is a guarantee for the consumer that they are getting what they paid for, exactly what the label indicates, an artisanal product produced by a specific producer from specific grapes using an age-old traditional process. And it also guarantees certain characteristics, a recognizable personality. A Bordeaux or a Beaujolais, a Chinon or a Muscadet, a Sancerre or a Pouilly-Fumé, a Champagne or a Crémant d'Alsace, and a Coteaux du Layon each have their own distinct personality, and what makes each unique is reflected in and guaranteed by the AOC, the taste and quality one expects and desires. These rules and regulations are overseen and strictly regulated by committees, both national and local; they ensure that each and every producer follows each and every rule, thus protecting the integrity of each appellation, ensuring that every bottle of wine reflects its label, its origin, and its heritage. Distinguished? Yes, indeed, and that’s reflected in the price you pay per bottle compared to wines that are not protected or guaranteed by a label.

How does one learn all of those 363 wines? The more wines you explore, the more you begin to notice and appreciate these subtle (and sometimes not-so-subtle) differences. If you're not familiar with specific wines yet, start broad: regions like Alsace, Bordeaux, the Southwest, Burgundy, the Rhône Valley, and the Loire Valley each offer distinct styles and flavors. This is how you will find wines organized in wine shops and supermarkets, and often on restaurant or bar menus, as well. Find your region that corresponds to the taste profile you’re looking for, and then start perusing the whites, reds, rosés, and sparkling. Then find a domain.

Among these regions, the Loire Valley—home to Chinon and also where I live—is especially known for producing wines that are wonderfully drinkable and well-suited for everyday. This region - Chinon is more or less in the middle of this huge expanse that follows the Loire River from Pouilly-Fumé and Sancerre to Muscadet and Gros Plant around Nantes - contains 80 different AOC labels spread across 5 distinct regions. Spend some time in France, travel around, and you’ll start to pick it up.

And, yes, this goes for many other food products. Roquefort, Brie de Meaux, Camembert de Normandie, Neufchâtel; like French wines, you already know certain cheeses by their AOC label. Just visit a cheese shop in France or even a stand or truck at any local street market and you’ll see all the different names, the guarantee that a cheese or butter is the real deal. (Go to the cheese aisle in any supermarket in France and you’ll see the industrial and semi-industrial cheeses without the guarantee of a label that attempt to visually copy the AOC/AOP label).

Do you have the impression that the soil flavors the fruit in ways that are unique to your region?

Back to my reader’s question. And the answer is yes. This is the concept of terroir.

Terroir has two meanings, but in truth they are one and the same: 1. the complete natural environment in which a particular wine (or product) is produced, including factors such as the soil, topography, and climate. 2. the characteristic taste and flavor imparted to a wine (or a product) by the environment in which it is produced. 256 food products in France benefit from protected status, recognized with a label. But more than this, all the foods and wines produced in a single region share a common terroir, and share certain characteristics. And, if I can carry this thought one step further, all the dishes and pastries of a region, made with those local products, the meats, fruits or vegetables, and the wine, express those unique characteristics, that singular personality.

Pick out a region and you’ll see what I mean. If the region produces a strong wine, its cheese will be salty, pungent, or strongly or deeply flavorful, its local dishes rich and hearty. Find another region with a more delicate wine, and you’ll find that the local products are, as well. And from the concept of terroir, we get the expression “If it grows together, it goes together.” What wine to choose for a meal? Find the region of the foods you’re eating, and the wine of that same region is guaranteed to match perfectly.

Let’s get to my region…. And its drinkable reds, refreshing rosés, and crisp whites. Its goat cheeses of Saint-Maure-de-Touraine, from the fresh unsalted to the creamy, tangy demi-sèche. Its fields of saffron and forests of truffles and walnuts. It’s asparagus, apples and pears, strawberries and raspberries. All wonderfully delicate and refreshing, all quite earthy.

If you have any more food-related questions, please don’t hesitate to ask in the comments!

And if it grows together, it most definitely goes together.

I let my reader’s question inspire this recipe. I combined two wonderful local ingredients, fresh goat cheese and asparagus, to make a simple, fun, and tasty little tart for every day.

Tarte aux fromage de chèvre frais et aux asperges

Fresh goat cheese and asparagus tart

I wanted to use the local plump, violet-tipped, white asparagus, but felt that the thin, tender, more flavorful green stalks would work better and look prettier.

Pure butter puff pastry for one tart - 10 ounces / 280 grams - homemade or good store-bought

1 egg yolk

1 bunch of thin, green asparagus - about 1 pound / 500 grams

7 ounces (200 grams) salt-free fresh goat cheese, drained if necessary

2 to 4 tablespoons heavy cream

3 to 4 tablespoons (30 to 40 grams) finely grated Parmesan, fresh or good quality packaged

Fine zest of 1 lemon

Pinch nutmeg

Salt and freshly ground black pepper

Olive oil

Preheat the oven to 350°F (180°C).

Roll out the puff pastry to a thickness of about ⅛ inch - or unroll, if using store-bought - and trim off the edges to make a rectangle; your rectangle of puff pastry should measure approximately 9 x 10 inches (23 x 24 cm).

Place the pastry directly on a baking sheet (you can place the pastry on a sheet of oven parchment paper, but baking directly on the baking sheet helps the bottom of the pastry crisp; I baked mine on parchment, carefully sliding the tart off the parchment and onto the baking sheet for the last 10 minutes or so of baking time).

Using the point of the blade of a knife, carefully mark an edge or border of about ¾ inch ( 1 ½ cm) along each side of the rectangle, being careful not to slice through the puff pastry. Using a pastry brush, lightly brush these marked edges with egg yolk all the way around. Set the pastry aside.

Rinse the asparagus and pat dry. Snap off the bottom half of each stalk, removing the fibrous ends, leaving only the tender tips. All of the asparagus tips left should be more or less the same length. You can discard all the bottom halves of the stalks or reserve for another use. Using a very sharp blade and working very slowly, slice each asparagus stalk (the top halves) lengthwise into two.

Place the fresh goat cheese in a bowl. Add 2 tablespoons cream, 2 tablespoons (20 grams) of the grated Parmesan, the fine zest of 1 lemon, a pinch of nutmeg, and salt and freshly ground black pepper, being careful not to salt too much as the Parmesan is salty.

Using a fork, mash and stir all of the ingredients together until really well blended; if your goat cheese in on the dry side, less creamy - mine was - add an extra 1 or 2 tablespoons of cream until creamy and smooth. Taste and adjust the seasonings.

Using a fork, carefully prink the puff pastry within the edges (the pastry not brushed with egg wash) a little bit all over; this should help keep the center of the tart from puffing up during baking. Scrape the goat cheese filling into the center of the pastry and, very carefully and using a long blade, preferably something like an offset spatula, spread the filling evenly across the pastry - staying within the marked outer edge - into the corners and up to the edge of the beginning of the egg wash.

Line up the halved asparagus tips down one side of the rectangle, pushing the tips closely together, tips out, then down the other side. Don’t worry if they overlap a bit in the middle, they will shrink during baking.

Drizzle the asparagus with olive oil and sprinkle with another 1 to 2 tablespoons grated Parmesan.

Bake in the preheated oven for about 40 or 45; the other edges should be well puffed, a deep golden brown, and crispy. The center shouldn’t look uncooked. Don’t worry if it’s puffed up a little.

Remove from the oven and immediately - carefully - slide the pastry directly onto a cooling rack - this allow air to help dry the bottom of the pastry and crisp up as it cools. The filling will firm up as it cools.

Serve cut into squares!

Make a larger tart - or 2 - by doubling everything!

Thank you for reading and subscribing to my Substack Life’s a Feast. Please leave a comment, like and share the post…these are all simple ways you can support my writing and help build this very cool community. If you would like to further support my work and recipes, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. It’s truly appreciated.

Fantastic writing Jamie. I always love how you focus on history & facts around food in your writings.

Thank you, Jamie. I found the terroir information both wonderfully explained and overwhelming! Oh, to have been raised in France and learned it organically. But I decided to completely give up alcohol 2 years, so, no matter now -- I'm off wines and even my beloved Scotch.

As I've grown older I find goat cheese to be a bit too tangy for my tastes, but maybe I'll look for a decent Vermont goat cheese and blend it with a similarly-decent mascarpone, unless you have a better recommendation. Cheers!