Bettelmann

Alsatian Bread Pudding with Apples and Raisins

Pastry making is an art full of imagination and variation. — Édouard de Pomiane

Like clafoutis and flognarde, the bettelmann belongs to a long tradition of modest home desserts. The name — bettelmann in the local dialect from the German, mendiant in French, “beggar man,” — in itself is revealing, an unambiguous marker of its origins as a dish of prudence and thrift, created to use up stale bread so that absolutely nothing went to waste, a reference to the dessert’s humble simplicity and its reliance on basic ingredients or leftovers — frugal, ingenious, and rooted in a domestic tradition that stretches back to the very beginnings of home cooking.

“I know a man from Strasbourg who lives in Paris. He likes

To go to Knôpfelfritz from time to time to eat

Sauerkraut and bacon, or delicious Knôpfles,

Or Knackwurst from Flamm. But this fellow countryman

On a certain holiday, unfaithful to his host,

Went to feast in a good restaurant Near the Palais Royal. Our man is brought

The menu, which he scans distractedly. But when

He suddenly sees this beautiful word: Mendiant!

He says to himself: “Well, well, well! In our dialect

We say a Bettelmann! Ah! Well! I delight

In remembering how my mother made

This dish, using small milk rolls,

Adding milk, butter, eggs, not forgetting cinnamon

Or sugar, or great care. She made them

So that each of us could enjoy them.

This memory touches me from my childhood days,

And just thinking about it makes my mouth water.

Waiter! Un mendiant!”

He rubs his hands together,

Believing he will feast and satisfy his hunger.

- from the Revue D’Alsace - 1 January, 1882

Whether this classic poor man’s dish is ancient or a more recent invention remains open to debate, though it hardly matters. What we do know is this: the bettelmann was originally a German pudding that slipped into Alsace, becoming French along with the region itself.

We’ve seen this kind of home baking before — uncomplicated, deeply and deliciously comforting — from the tôt-fait to the soufflé au pain. The bettelmann belongs squarely in this family of dishes, prepared for intimate household gatherings or for well-behaved children, and served warm from the oven. You won’t find recipes like these in many cookbooks, yet the bettelmann is an important element of Alsatian cuisine. Like riz au lait, it was also a practical way to fill bellies and plump up children at times when meat was scarce.

I won’t say much more about the bettelman, because, frankly, there’s not been much written about it across the centuries. I have already traced the very interesting history of bread pudding, what the French call pouding, a sweet dish who’s origins are less than sweet. Puddings were originally little sausages called boudins - think “blood pudding” or “white pudding” - a way to preserve and easily transport meats as early as the 4th century (its first appearance in a cookbook). By the Middle Ages, versions of boudins, white sausages, were made of bread, fat, milk, starch, and either ham or chicken, originally a type of porridge then simply pushed into pork casings. Sugar was often added as a persevering agent, dried fruits and spices added as seasonings. Little by little, the meat was replaced by more and more bread, the dried fruits and sugar increased, and somewhere along the way, the word boudin transformed into pouding or pudding.

This is easily explained by Jean Nicot, whose Dictionnaire François-Latin (1584) translates boudin as botellus or farcimen (farce meaning stuffing). Little changed — either in language or in preparation — for nearly two centuries, until the Dictionnaire Universel Français et Latin of 1752 includes an entry for poudin, defined as “the same thing as boudin, whose English name changes the B to P. They write puding.”

See?

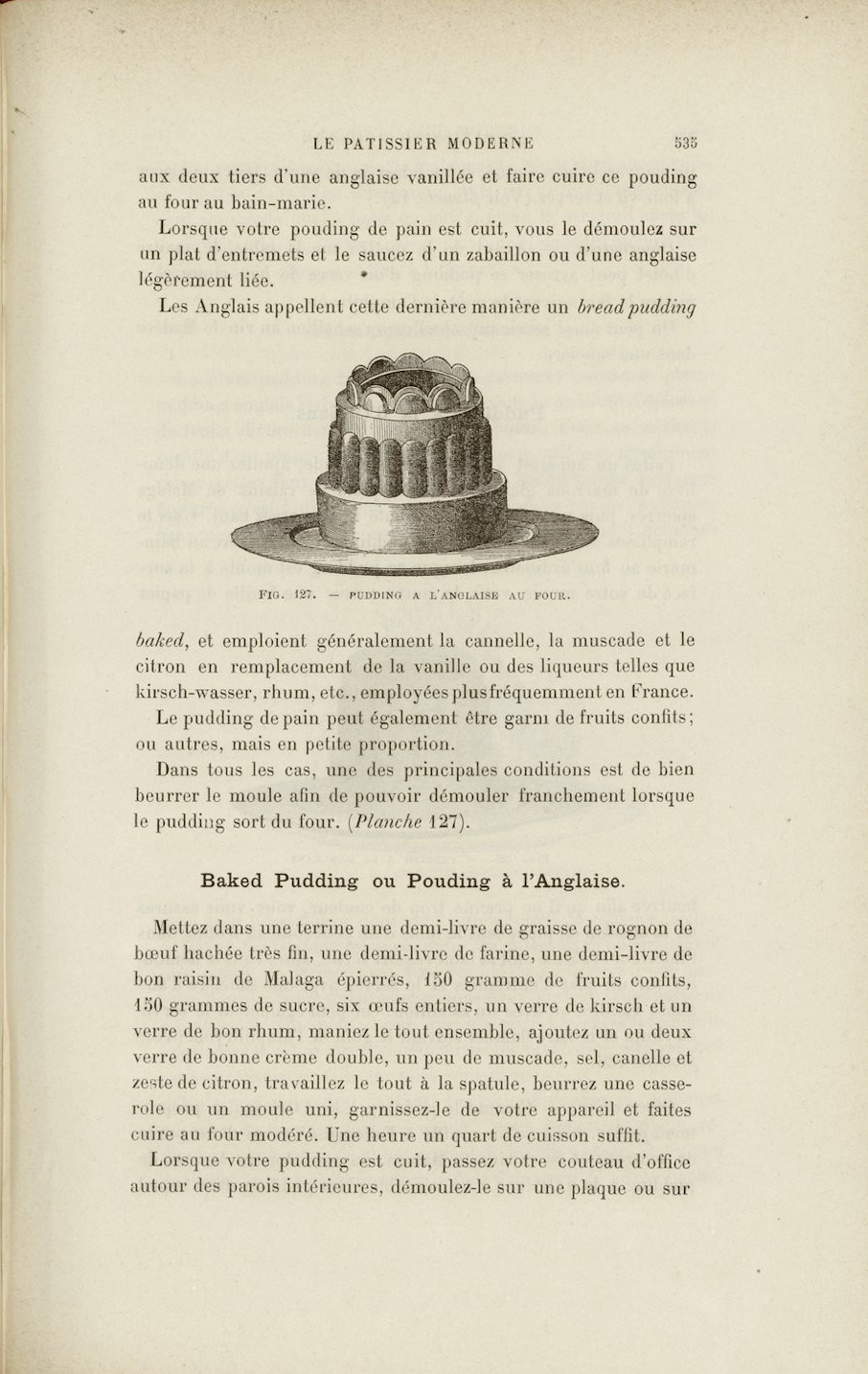

We then see the evolution of boudin into poudin — and from primarily savory to sweet — illustrated in François Massialot’s Le Nouveau Cuisinier Royal et Bourgeois (1730), perhaps the first published recipe in France for a poudin, or pudding. Massialot offers a poudin cuit au four (a pudding baked in the oven) and poudin boüilly (boiled porridge pudding). Both are sweet, yet the base is “4 pounds of beef fat.” Both are flavored with chopped candied lemon peel, a pound of Corinth raisins and a pound of seeded Spanish grapes, and bound with 15 raw egg yolks, half a pound of white bread soaked in milk, and half a pound of sugar. No longer stuffed into a sausage casing, the first pudding is spread and baked in a pan; the poudin boüilly is wrapped and tied tightly in a “white napkin” or cloth and boiled.

With this, the modern bread pudding can be said to have been born.

This, too, seems to be the moment when puddings prepared with bread began to enter British cookbooks, starting with The Complete Family-Piece; And, Country Gentleman, and Farmer’s, Best Guide, 1737, with a rye-bread pudding, and Hannah Glasse’s The Art of Cookery, Made Plain and Easy, 1737, with “To make a bread pudding” using a “penny white loaf” and “To make a fine bread pudding” using “a stale penny-loaf”. Both Glasse’s orange pudding and Oxford pudding uses grated biscuits for a starchy thickener.

And yet, this evolution was by no means linear. Bread was only ever one variation among many. In both France and Britain, puddings continued to be prepared primarily without bread, relying instead on flour, eggs, cream, fat, or fruit for structure. Bread entered the repertoire as a practical and economical thickener, as it had long been used for sauces, soups, and stews, not necessarily as the defining feature of the dish.

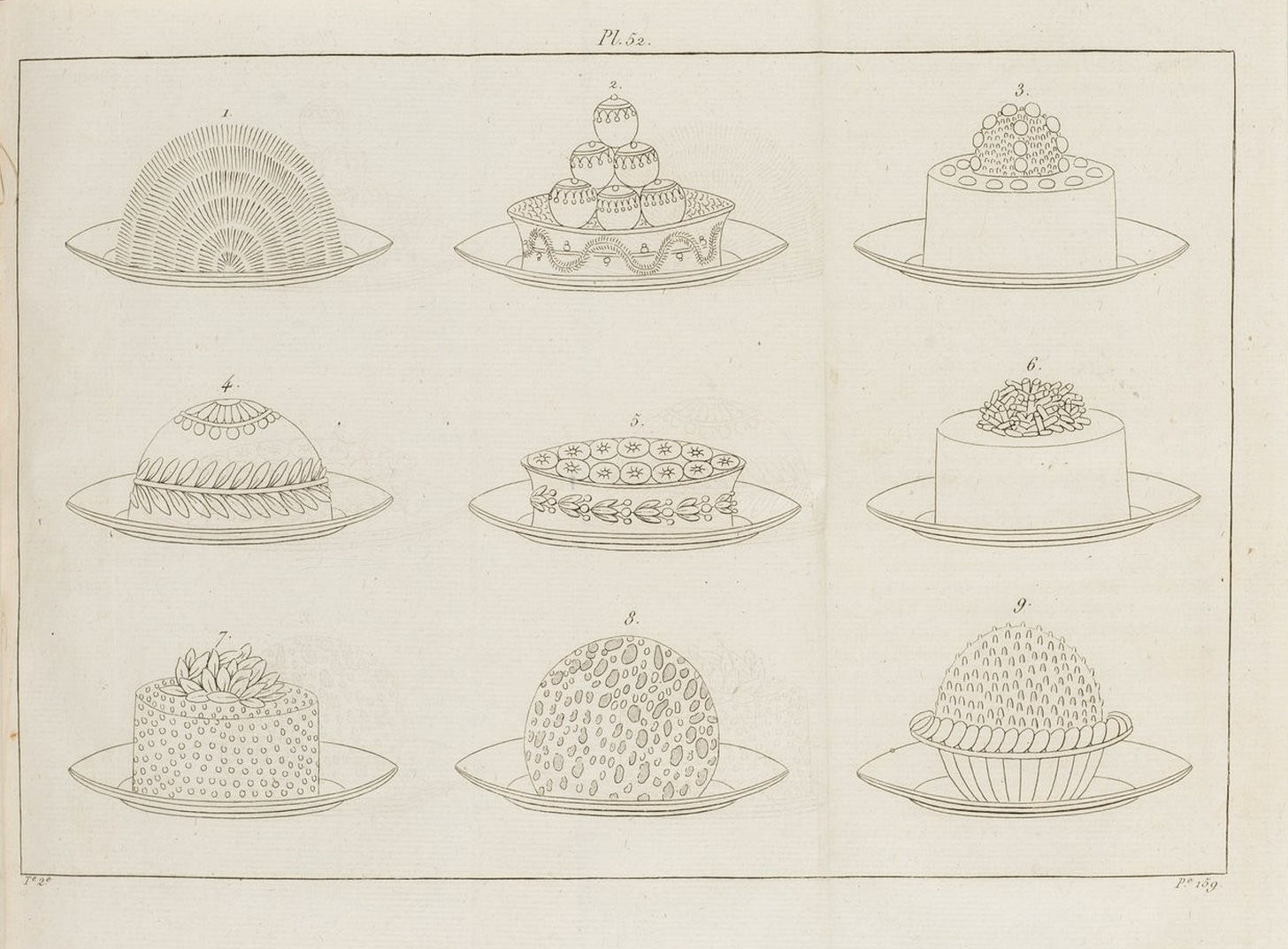

Point of fact, I want to note here that Joseph Menon’s English Pudding or Pouding à l’Angloise from his 1755 cookbook Les Soupers de la Cour is made with flour, eggs, cream…then “pralined orange blossoms, chopped green lemon peel, six eggs, beaten egg whites, a pound of chopped beef fat, melted but not browned, a small handful of currants or raisins from Provence, twelve dried figs, all well mixed.” It is then placed “in a pan that is the right size for the dish you are going to serve; bake in the oven for an hour; serve drained of its fat.” Half a century later, Antonin Carême’s Le Pâtissier Royal Parisien is filled with recipes for puddings of all sorts, almost all fruit based.

No bread in sight.

And yet, it’s here at the period, finally, that the name pouding entered into the Dictionnaire de l’Académie Françoise, in 1762, and defined as the “name of a dish made from breadcrumbs, beef marrow, currants and other ingredients. Pudding is an English stew.” In the same year, the Dictionnaire Domestique Portatif describes it as a pastry.

For all this — for all the high-end cookbooks aimed at fancy kitchens — if we’ve learned anything from studying French home cooking, it’s that recipes at this time were still passed down orally, from mother to daughter, and would not appear in French cookbooks for at least another century. In modest and rural homes, cooking remained above all practical, shaped by necessity, availability, and a careful domestic economy. Dishes designed to use up stale bread were part of this everyday logic. It’s more than likely, then, that bread-based puddings were being made long before they ever appeared in those high-end kitchens — perhaps even influencing their creation.

And this is exactly where the bettelmann comes in.

What we do know is that this particular bread pudding arrived in Alsace from Germany. But like French bread-based puddings, the bettelmann (or Apfelbettelmann) does not appear in major printed cookbooks before the 19th century, and then primarily in regional ones. In France, its earliest mentions appear only in German-language publications — and only in Alsace.

What makes the bettelmann unique is that it was most commonly made using leftover enriched sweet breads such as pains au lait or kougelhopf, both deeply rooted in Alsatian home baking and staples of the kitchen. And because these breads - rich with eggs, butter, and milk - were costly to begin with, it was all the more imperative they not be thrown away once stale.

To make it an even tastier, more special treat, the bettelman is and always has been, sweetened with apples and raisins in the autumn and winter, and local plump black cherries in the summer months.

Creamy when warm, the bettelman becomes denser and chewier at room temperature. Eaten either way, it’s the best bread pudding we have ever eaten. I can’t wait for summer to make it with cherries.

Bettelmann

Alsatian Bread Pudding with Apples and Raisins

While the bettelmann can be made with any plain stale bread, baguette or white bread, the brioche does offer more sweetness and richness to the dish. I imagine as the origins of the bread are German and Alsatian, a lightly sweetened, enriched kugelhoff or brioche-style pains au lait were traditionally used.

10.5 ounces (300 grams) stale brioche or bread

2 cups (500 ml) milk

2 or 3 small or medium small apples (Reinettes, Boskop, Melrose, Idared, or similar)

¾ cup (100 grams) plump raisins

3 eggs

½ cup (100 grams) granulated white sugar

½ teaspoon ground cinnamon, or up to 1 teaspoon

1 teaspoon vanilla extract

1 tablespoon (15 grams) or a bit more softened unsalted butter

1 - 2 tablespoons fine breadcrumbs (you can grind or grate the crusts of the stale bread)

About 1 tablespoon dark brown sugar, optional

Preheat the oven to 350°F (180°C). Butter a 9 ½ - inch (24 cm) wide x 2-inch (5 cm) deep baking pan.

Cube the stale brioche or bread and place in a large mixing bowl. Bring the milk just to a simmer, without allowing it to boil, then pour it over the bread. Using the back of a tablespoon, press the cubes firmly into the hot milk until the bread has absorbed all of the milk and is beginning to form a thick, soft mixture. Continue to press and stir the bread occasionally while you prepare the apples, allowing the bread time to completely soften and meld almost into a purée.

Peel, core, and cut the apples into cubes or thin slices.

Whisk the eggs and sugar together until smooth and slightly creamy. Whisk in the vanilla.

Dust the cinnamon evenly over the softened bread and stir vigorously to combine. Pour the whisked eggs, sugar, and vanilla over the mixture and stir until fully incorporated. Add the raisins and apples, then stir until evenly distributed throughout the batter.

Pour the bettelmann batter into the buttered baking pan and smooth the top. Dot with butter, dust with fine breadcrumbs, and, if you like, dust with dark brown sugar.

Bake in the preheated oven for 1 hour or until the bettelmann is puffed and the surface is golden and slightly crisp. The pudding should have begun to pull away from the sides of the pan.

Allow to cool for several minutes before slicing and enjoying. Wonderful with whipped cream.

Thank you for reading and subscribing to my Substack Life’s a Feast. Please leave a comment, like and share the post…these are all simple ways you can support my writing and help build this very cool community. If you would like to further support my work and recipes, please consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Interesting! I grew up in the Alsace neighbouring Palatinate (Pfalz, Germany), and we have the same recipe with cherries called Kerscheplotzer in the local dialect! Thanks for providing me with this excellent recipe!

Thank you for this very interesting article. I was very surprised to see the reference to knôpfle or knöpfle as it was a staple comfort food in my family which I have also passed down to my son. It came down from my maternal German grandmother who grew up in the Alsace region. It consists of an amount of flour mixed witih enough whole eggs to make a thick batter figure one egg per person. The batter is then put on plate and cut into boiling water with a sharp knife off the edge of the plate. It is served with thinly sliced onions braised in copious amounts of butter. Very vague recipe, but it is so good! Thanks again!