Baked Chocolate Tarts with salted caramel drizzle

Chocolate Part 3: the 19th century, beets, mass production, and the democratization of chocolate and pastry

Happy chocolate, who, after traveling the world through the smiles of women, finds death in a delectable, indulgent kiss on woman’s mouth. - Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin

Ah, that age-old dispute between the French and the British, am I right? It’s become a punchline today, but in this new century, the 19th, of course, and France with a new leader, the war between these 2 ancient kingdoms played a huge role in the democratization of chocolate.

While the rest of Europe had been moving ahead at a clip, France moved gently forward during a century and a half to find, at the wake of the 19th, an exciting new vigor where chocolate was concerned. But chocolate still remained a luxury item; the cost of both the ingredients, primarily sugar, and the production from cocoa to chocolate, which was still mainly manual, made it expensive, only available to the upper crust. But that would soon change.

This is where our immortal love-hate rivalry comes into play. In 1806, Napoleon proclaimed an unprecedented blockade of continental Europe in order to isolate and weaken the United Kingdom. The UK, with whom France would wage war - and particularly a trade war - for much of the early years of the new century, was denied access to major European ports, forbidding imports of British goods to the continent. But this, among other difficulties, cut off France’s supply of sugar which either came from the colonies through the UK or directly on French ships which were in turn blocked by the UK under similar retaliatory measures.

And this, of course, affected the chocolate industry.

If the French couldn’t get cane sugar from the colonies, where could they get this coveted commodity? From the humble beetroot.

Producing sugar from beets had been studied and tested in Europe, and France, if we are strictly speaking, since the 16th century, but with the ready availability of cane sugar, while extremely expensive, the exploitation of beets had never really moved forward. Until France could no longer get cane sugar. Thanks to Jean-Antoine Chaptal, agronomist, chemist, and statesman, and his report on the “instruction on the manufacture of beet sugar”, producing sugar from beetroot caught Napoleon’s attention.

Napoleon, possibly driven by a sweet tooth, possibly driven by the knowledge that “he who makes the sugar rules the world”, began encouraging sugar beet cultivation by offering premiums and other benefits to growers who took up the crop. In March 1811, Napoleon signed an Imperial Decree ordering the cultivation of 32,000 hectares of beets. In 1812, another Imperial Decree introduced beet sugar manufacturing licenses in a move to encourage local sugar production. By 1814, over 200 beet sugar factories were in operation. By 1828, France had 585 sugar factories in 44 departments across the country. By mid-century, sugar had become abundant, cheap, and now economically available to all, not only the upper classes. That’s a lot of beets…

And this new, less expensive sugar would now be used to make chocolate.

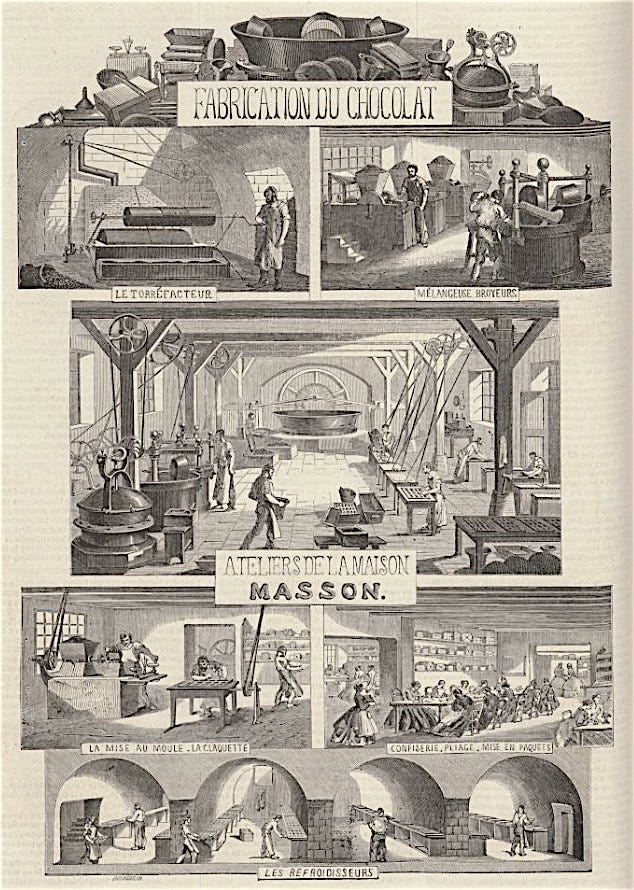

Meanwhile, advances in chocolate production were taking off. The years between 1810 and 1830 saw the fast-paced evolution of the chocolate industry in France, inventions and progress spreading like wildfire from one maker to the next. Poincelet, Pelletier, Menier, Ibled, Antiq, Mélinans, Devinck, Duthu, engineers, chemists, pharmacists, men who brought their knowledge to the chocolate industry, were responsible for developing the machines that turned chocolate making from a slow, manual, inaccurate process to a fast, precise, mechanized, steam and hydraulic-powered business. They invented machines that ground the cocoa bean into paste, blended the paste with sugar and other ingredients with ever-increasing efficiency and precision, kneaded and aerated the liquid chocolate, and machines that then weighed and molded it. Chocolate was now produced with more finesse and uniformity.

The elimination of labor costs through machine intervention lowered the price of the finished chocolate, creating a product economically available to more and more people. According to L. de Belfort de La Roque’s Guide pratique de la fabrication du chocolat, A Practical Guide to Chocolate Making, published in 1875, chocolate consumption in France went from 30,000 kilograms in 1780 to 1,500,00 kg in 1836 and 5,000,000 in 1860. By the writing of his book, that figure had doubled. To take another example, Chocolat Menier’s workforce alone went from 50 workers in 1856 to over 320 in 1867, then to more than 2,000 in 1874; in 1869 the Menier factories were churning out 3,850 tons of chocolate and by the end of the century, it was claimed that his 2,200 employees made 70 tons a day. That’s a lot of chocolate…

And it wasn’t just the chocolate itself. The 1866 revue L’Année scientifique et industrielle (The Scientific and Industrial Year) published a profile on François-Jules Devinck, engineer and chocolatier, who, with his foreman Armand Daupley, not only developed machines that roasted, ground, and mixed, making the chocolate blend homogenous, and then weighed and molded the chocolate into tablets, but, even more spectacular for the time, they invented the chocolate-wrapping machine which wrapped and packed 20 to 30 tablets a minute (about 2,000 to 3,000 a day) in tin-lined paper, truly modernizing the chocolate industry. (Why do I now have images of Willie Wanka whizzing around in my head?)

So now that France is producing literally tons of chocolate, and so many Frenchmen - those engineers, chemists, and pharmacists - have become prodigious chocolate makers, you just know that there had to be a bit of *friendly* competition. They are, after all, making chocolate for the same consumer base, even as that base grew in both socio-economic class and age groups. So how do they differentiate themselves from each other?

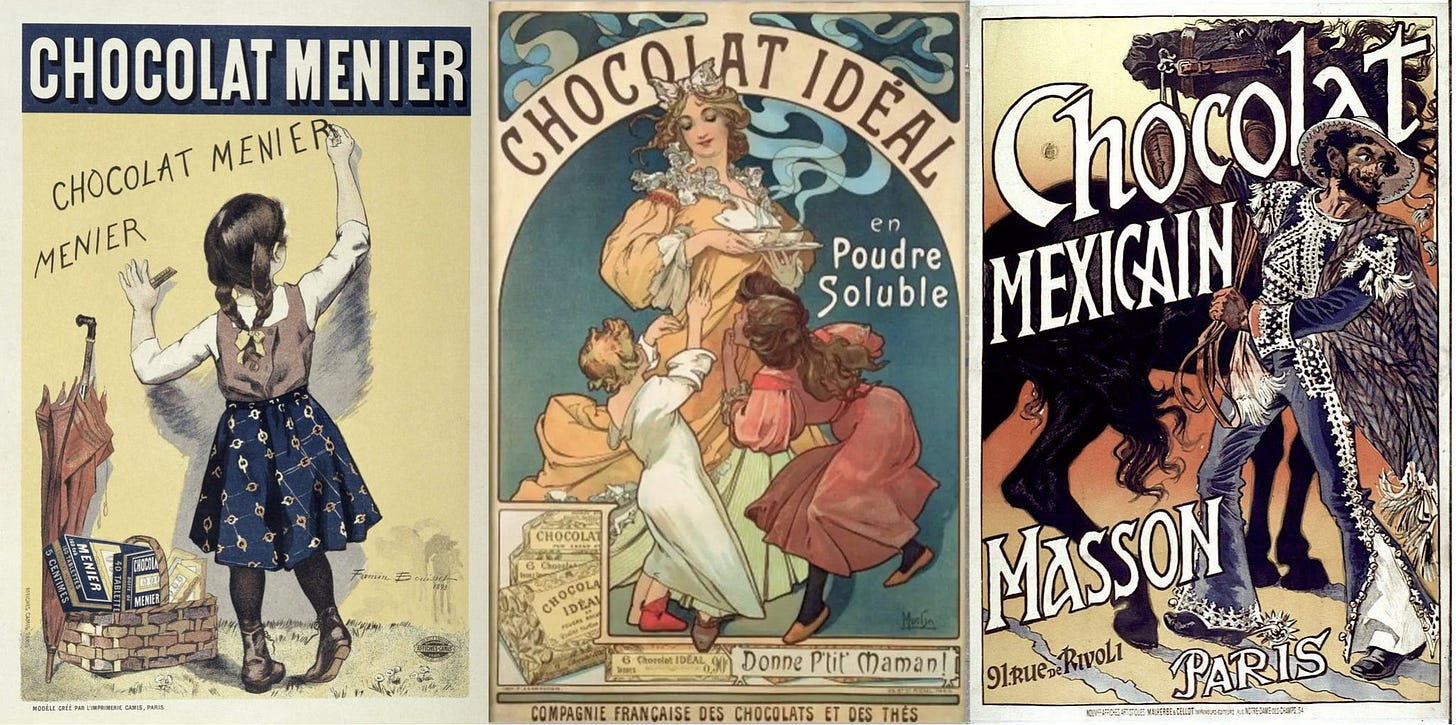

Henri Duthu of La Compagnie Française des Chocolats et des Thés had the idea for developing both the packaging and marketing of chocolate with elegant paper packaging around the tin foil wrapping, putting his name - the maker - on the label and thus offering a guarantee to the purchaser of the quality of the chocolate. This now allowed each chocolate maker and company to create a personality, a brand that would become a symbol of quality and prestige among their consumers. From packaging and labels to posters, postcards, collectibles, and ads, chocolate makers began investing in promotion and marketing, making chocolate more and more familiar and desirable to a more general public. Jean-Antoine-Brutus Menier, as one example, not only invented the chocolate bar in the form of 6 semi-cylindrical bars, but he decided to wrap them in bright yellow paper, reproducing his signature and the medals he had won at exhibitions on the label, creating an immediately recognizable brand. Both La Compagnie Française des Chocolats et des Thés and Chocolat Masson hired famed Czech artist Alphonse Mucha to illustrate their publicity from posters to calendars while other chocolate houses were hiring other illustrators and artists to create mouthwatering, appealing images for their products.

Chocolate has now become almost commonplace. It is taking on a greater role in the public diet, one of the “preferred foods of the affluent classes, and (tending) to play a major role in the diets of the working classes,” according to M. Delafontaine and M. Dettwiller, directors of the Masson chocolate company, in the manual they wrote in 1859 on Le Chocolat, “a food that deserves the name food of the gods”, specifically written to explain the industry to the new consumer.

Remember how chocolate had become a health food in the former centuries, playing a role in medicine, pharmaceutics, and health regimes? While chocolate is now, in the 19th century, most decidedly a confectionery consumed for pleasure, chocolats de santé are still being made and sold, often by the same chocolate companies. Analeptic, tonic, stomachic, ferruginous, and purgative chocolates are still being sold in pharmacies across France and prescribed by doctors.

Eugène and Auguste Pelletier, directors-managers of La Compagnie Française des Chocolats et des Thés, put it succinctly in their own publicity pamphlet Le Thé et le Chocolat dans l'Alimentation Publique, Tea and Chocolate in the Public Diet in 1861: “The enormous progress made in less than fifty years in the consumption of two foodstuffs (cocoa and tea) that can almost be considered as luxury foods as well as basic necessities, is the best proof we can give of the progress being made in the nation's habits of well-being; but above all, it proves the rapid progress of our trade and industry.” The brothers, while not wanting to wade into the medical use of chocolate, a subject, according to them, best left to the doctors and scientists, did, nonetheless reiterate the health benefits put forth in the last century and in my last 2 posts, illustrating that these claims are still popular, respected, and de rigueur; chocolate is good for the stomach, the liver, the throat, blood circulation and the heart. They reiterate that chocolate is medicine's best restorative as well as “warding off hypochondria and the melancholic affectations brought on by nervous overexcitement. Organisms exhausted by pleasure or the sufferings of misery, extinguished by languor, lethargy or lack of fluid action, find new life in (chocolate).”

In other words, one could enjoy the luxury and pleasure of chocolate knowing that it was good for one’s health, as well. Win-win, oui?

With chocolate now more readily available and so widely consumed, pastry chefs are stepping up, as well.

Well, almost…for some it still seems to be a strange new ingredient. André Viard’s 1806 edition of his popular Le Cuisinier impérial only mentions chocolate one single time, in suggesting serving a chocolate flan in a menu, not even offering the recipe. By the time he published Le Cuisinier Royal in 1817, he’s included a whopping 3 recipes(!!!) which use chocolate - crème de chocolat, biscuits au chocolat, conserves de chocolat, and again mentions the chocolate flan yet again without giving a recipe. His 1844 edition adds only 3 more: chocolate mousse, ice cream, and soufflé, as well as a recipe for the liqueur crème de cacao, not much more than others were publishing half a century or so earlier. Urban Dubois, another extremely well-known and influential chef and cookbook writer of the period barely mentions chocolate in his voluminous Nouvelle Cuisine Bourgeoise (200 menus) of 1888, including only recipes for mousse au chocolat, pots de crème au chocolat, which could also be used to make oeufs en surprise au chocolat (in which one gently poaches the chocolate cream in cleaned egg shells), and a chocolate soufflé.

Leave it to "the king of chefs and the chef of kings” to really innovate in the realm of pastry. It’s no surprise that Marie-Antoine Carême, one of the most prolific and ingenuous pastry chefs of his day and beyond, would be on the cutting edge of chocolate innovation.

While Viard was tiptoeing into the arena for the first few decades of the new century, Carême jumped right in with much swagger and panache with a panoply of chocolate recipes in his earliest cookbook Le Pâtissier Royal Parisien of 1815, from a simple crème fouettée (whipped cream) and a crème patissière, to blanc manger to meringues à l’italienne from petits pains to crème française, cannelon à la parisienne, fromage bavarois, génoise, petits soufflés, and macarons soufflés. Each and every one au chocolat.

His ingenuity in turning simple elements into a multitude of entremets - desserts composed of several components - is also evidence of Carême’s genius: bouchées de dame glacées au chocolat (ladyfingers shaped in rounds or ovals, topped with jam then iced with chocolate glaze), les petits pains à la duchesse (choux puffs filled with chocolate pastry cream and topped with chocolate icing), les profiteroles (the same as les petits pains à la duchesse “except for the way they are served”), fanchonettes (puff pastry shell, chocolate cream, meringue). Another of Carême’s great innovations included using chocolate to create a marbled effect in both pastries and candies - biscuits de couleur marbrée, pâte d’amande - marzipan - marbrée au chocolat, rochers.

By 1879 and his Pâtissier National Parisien, Carême has integrated chocolate into many of his grand architectural desserts - large pièces montées assembled from many different dessert components that were used as splendid table centerpieces often decorated with sculpted sugar and depicting classical buildings, Carême’s particular passion - adding chocolate cream and whipped cream, chocolate marbled almond paste, chocolate meringues, chocolate icing, chocolate biscuits and genoise. He understood that most recipes for pastries, cakes, entremets, cookies, and candies can be filled, or garnished with chocolate creams and icings and chocolate can be added to almost any basic dough or batter.

Jules Gouffé, after having worked alongside Carême for 7 years, became himself a celebrated chef and pastry chef in his day, eventually working as head chef for Napoleon III, and extremely influential in the history of French cooking, earning himself the nickname “l’apôtre de la cuisine décorative”, the apostle of decorative cooking. He was the author of several cookbooks, among which Le Livre de Pâtisserie, The Book of Pastry, in 1873. And while Carême primarily wrote his books for fellow professional chefs who were cooking in illustrious kitchens, Gouffé aimed his books at bourgeois households, for the woman of the family and her cook, the same public Dubois wrote his Nouvelle Cuisine Bourgeoise for. His book, unlike Dubois’, has an array of interesting new recipes made with chocolate, from cookies to icing, a Saint-Honoré made with a chocolate bavarois cream, chocolate flan (finally a recipe!), and quite a number of mounted or complex desserts including compositions of chocolate cakes, creams, flans, cream-filled choux, and icings. Oddly enough, Dubois’ Grand Livre des Pâtissiers et des Confiseurs which he wrote in 1883 for students learning the art of pastry rather than for the general public, or at least the bourgeois public, was filled with recipes using chocolate, so professionals worked with chocolate, but bourgeois households weren’t ready for the innovation?

Louis Bailleux explains this conundrum in his astonishing cookbook Le Pâtissier Moderne ou Traité Élémentaire et Pratique de la Pâtisserie Française au Dix-Neuvième Siècle (The Modern Pastry Chef or Elementary and Practical Treatise on Nineteenth-Century French Pastry-Making) of 1856. He begins by explaining that until the 19th century, pastry was just an accessory to the culinary arts and cooking. Today, he continues, “pastry has become an everyday necessity in our tastes and habits.” It has become such an art that instruction is necessary to truly showcase what it is and can be. Up until now - mid 19th century - the books that have come out on pastry, according to Bailleux, have been directed at professionals and thus been written as an extension of cooking rather than an art in and of itself, thus creating confusion for the average home cook. While extolling the greatness and genius of Antonin Carême, Bailleux sees his works as “grand operations and fabulous sculptures”, grand gestures written by a grand chef that are impossible for a home cook to recreate. Bailleux’s goal with his book is to simplify the procedures for the home cook (or the household cook), write a simplified and practical pastry manual that brings the art to the general public. That said, he only has a dozen or so recipes for chocolate pastries - most of what we’ve already seen. He does include instruction on how to make chocolate - sweetened or unsweetened - from the cocoa bean - which I find extraordinary. But it does explain why some cookbooks of the day have few recipes using chocolate while others have many, now using chocolate as the common kitchen ingredient it finally became in the 19th century.

It has been shown as proof positive that carefully prepared chocolate is as healthful a food as it is pleasant; that it is nourishing and easily digested… that it is above all helpful to people who must do a great deal of mental work. – Anthelme Brillat-Savarin

Baked chocolate tartlets

Makes 6 individual tartlets, each 4 to 4 ¼ inches / 10 ½ to 11 cm wide

An absolutely stunning recipe, these baked chocolate tartlets begin with a tender crust based on the French style of replacing granulated sugar with powdered and adding milk to the egg used to bind the dry ingredients into a dough. The filling is mousse-like, light, and airy from whipping then brief baking, creating a delicate, meltingly ethereal, elegant little dessert. For the chocolate lover.

For the pie crust:

1 ¾ cups (250 grams) flour

⅓ cup (40 grams) powdered/icing sugar

8 tablespoons (115 grams) unsalted butter, slightly softened, cubed

1 large egg yolk

Scant ¼ cup (50 ml) milk, slightly more if needed

The Chocolate Filling:

3 ½ ounces (100 grams) good-quality dark bittersweet or semisweet chocolate (70%)

8 tablespoons (110 grams) unsalted butter

4 large egg yolks + 1 large whole egg

¼ cup (50 grams) + 2 tablespoons (30 grams) granulated white sugar, as needed

The Salted Butter Caramel Sauce (Caramel au Beurre Salé):

1 cup (200 grams) granulated white sugar

3 ½ tablespoons (50 grams) salted butter

1 cup (250 ml) heavy cream

Prepare the crust: Sift or whisk together the flour and powdered sugar in a large mixing bowl. Drop in the cubes of butter and, using the tips of your fingers and thumb, rub the butter and flour together quickly until all of the butter is blended in and there are no more lumps. Add the egg yolk and the milk and, using a fork, blend vigorously until all of the flour/sugar/butter mixture is moistened and starts to pull together into a dough.

Scrape the dough out onto a floured work surface and, using the heel of one hand, smear the dough inch by inch away from you in short, hard, quick movements; this will completely blend the butter in. Scrape up the smeared dough and, working very quickly, gently knead into a smooth, homogeneous ball. Wrap in plastic wrap and refrigerate for 20 to 30 minutes.

Lightly grease with butter the sides and bottoms of 6 individual tartlet tins (4 to 4 ¼ inches / 10 ½ to 11 cm wide) and place the prepared tins on a baking sheet.

Remove the dough from the refrigerator and unwrap. Working on a floured surface and with the top of the dough kept lightly floured to keep it from sticking to the rolling pin, roll out the dough and line the tins by gently lifting in and pressing down the dough. Trim the edges. Cover the baking tray with the lined tins with plastic wrap and refrigerate for 30 minutes. This can also be done ahead of time.

Preheat the oven to 350°F (180°C).

Remove the baking tray from the refrigerator and discard the plastic wrap. Cut or tear squares of parchment paper larger than each crust. Prick each tartlet shell with a fork (not too hard or deep as you don’t want holes going all the way through the dough) and place a square of parchment over each. Weigh down the parchment with pastry weights or dried beans, pushing the beans into the corners. Bake for 15 minutes. Remove from the oven, carefully lift out the parchment squares and beans, pressing the bottoms down with your fingertips if puffed up, and prepare the Chocolate Filling.

Increase the oven temperature to 400°F (200°C).

Prepare the filling and tartlets: Melt the butter and chocolate together in a heatproof Pyrex bowl over a pan of just simmering water or in a bain-marie, stirring gently, until just melted. Remove from the heat and allow to cool slightly. In a large mixing bowl using an electric mixer, beat the egg yolks and the whole egg with the sugar on high speed for 5 minutes until very light, airy and mousse-like.

Decrease the beater speed to medium, gradually beat in the melted chocolate and butter in a stream until blended.

Pour into the pre-baked tartlet shells, evenly dividing the chocolate filling between the 6 tins; using a soup ladle or measuring cup with a spout makes this easier. Slide the baking sheet with the 6 filled tins into the oven and bake for 8 minutes or until the top is just set, having formed a slight crust.

Remove from the oven, slide the tartlets off the baking tray and onto a cooling rack and allow to cool.

Prepare the Salted Butter Caramel Sauce while the tartlets are baking, allowing the Caramel Sauce to cool as the tartlets are cooling.

Melt the sugar in a medium-sized saucepan over low heat and cook until completely melted and caramel in color. Still over low heat, quickly whisk in the butter in 3 or 4 additions. While continuing to whisk, add the heavy cream in a slow stream; the caramel may foam up, but keep whisking, as it will calm down once all the cream has been added and will turn into a smooth caramel. Once it is smooth and creamy, remove from the heat and allow to cool (at least to warm) and thicken before drizzling over the tartlets.

Thank you for subscribing to Life’s a Feast by Jamie Schler where I share my recipes, mostly French traditional recipes, with their amusing origins and history. I’m so glad that you’re here. You can support my work by sharing the link to my Substack with your friends, family, and your social media followers. If you would like to see my other book projects in the making, read my other essays, and participate in the discussions, please upgrade to a paid subscription.

When I go to my special little park bench tomorrow morning, I will look across the street at the Spreckles mansion and wonder about "he who makes the sugar rules the world". That's putting a lot of pressure on sugar manufacturers, but I can definitely say that (for a time at least) that "he who made the sugar ruled San Francisco". Or at least his wife, Big Alma, did.

Fascinating take on the evolution of chocolate production, love the art work of confections that were so tantalizing, will be making these tarts closer to the holidays when the extra egg whites will come in handy for other bits. Thank you!